Motivation and emotion/Book/2023/Choice and emotion

How does emotion affect choice?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Emotions are a complicated, yet important element of being human.[1] Emotions can influence the decisions made in life, whether it's by how the circumstance is viewed, what coping methods are appropriate, or how to adapt to the problem.[2] In comparison to when one feels angry, being happy gives them more patience upon hearing "Sorry, our ice-cream machine is broken". Case study 1 demonstrates how anger can limit a person's capacity to grasp information, and facilitate more violent behaviours.[3] How could X have acted differently if they had been feeling another emotion?

In this chapter, theories and studies are discussed to illustrate the relationship between emotion and choice (see Figure 1). Understanding how emotions work may provide insight into how they can be better regulated, making it possible to improve mental functioning, social interactions, and overall quality of life.[1]

Focus questions:

|

Choice theories

[edit | edit source]

The decision-making process involves evaluation between one's needs and ways to fulfill them (see Figure 2).[4] Because each choice has several factors to be considered, there are typically no perfect alternatives that satisfy every single one of those aspects, making it harder to choose.[4] The quality of the decision-making process can be influenced by a range of things, one of which is the emotional state.[5] Too many choices can overwhelm the mind's capacity to make good judgements.[6] By telling us what one prefers, emotions can filter out the less desirable options, and reduce the workload of the mind.[5]

Affect-as-information model

[edit | edit source]The affect-as-information model model highlights how much information an emotion could convey about a situation, and how that information then impacts the decision-making process.[7] When feeling an emotion, one does not use all existing emotional information to help them decide; rather, they pick what they believe to be the most relevant to the main goal, and pay less attention to the others.[8]

For example, John experiences irritation from extreme thirst; he may not think to check the safety of the nearest water source before drinking it. Emotions evoked by other stimuli will not impact this decision-making process (e.g., his choice of clothing, the weather).

This explains the preference of specific items, activities, and decision alternatives when feelings a certain emotion.[9]

|

What aspects did you have to consider? What was the first option that was eliminated, and why?

|

Choice and emotion theories

[edit | edit source]Emotions are important in biological and social contexts, and are believed to assist in making adaptive decisions for evolutionary purposes, e.g., hunting and socialising.[3] Without accompanying thoughts, emotions automatically trigger a set of psychological and physical responses. These changes come from previously learned behaviours and current emotional experiences, allowing the individual to quickly counter any rising problems or opportunities.[10]

Valence-based approach

[edit | edit source]Valence is the perception of whether a situation is good or bad. It focuses on the important information that will motivate us to achieve our goals, impacting our judgments either directly or indirectly.[3]

| Integral (direct) affect | An individual's subjective experience influences their current assessment of the situation and the later decision-making process. For example, evaluating the predicted fear when going into a haunted house will influence one's willingness to visit.[11] |

| Incidental (indirect) affect | The human brain can unconsciously access information from memory that is related to an emotional experience. It can influence the judgment of a seemingly irrelevant topic.[12] For example, compared to someone who had a relaxing morning, taking a stressful exam can then affect how someone approaches a problem in the afternoon. |

Criticism: Though simple, it lacks specificity and fails to address how different emotions (happiness, surprise) of the same valence (positive) have varying antecedents (what happened prior to produce the emotion), physiology (bodily reactions), and influences.[13]

|

To address the limitations in the valence approach, the appraisal theories explains specific emotional influences more in-depth.[14]

Appraisal model of emotion

[edit | edit source]

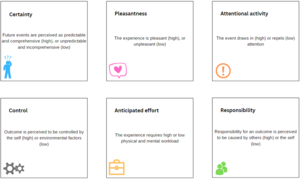

Emotions are defined and differentiated by 6 cognitive dimensions (see Figure 3).[15]

For example, anger is represented by appraisals of:

- High responsibility (belief that another person was responsible for the negative event)

- High control (belief that they can change the outcome)

- High certainty (certainty of what has happened)

This leads the individual to think they are aware of what is happening, and capable of changing the outcome of their situation, thus decide to protest or seek revenge.[8]

Table 3

Two illustration of appraisals and emotions

| Cognitive appraisal | Negative valence | Positive valence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Anger | Fear | Pride | Surprise |

| Certainty | High | Low | Medium | Low |

| Pleasantness | Low | Low | High | High |

| Attentional activity | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Anticipated effort | Medium | High | Medium | Medium |

| Control | High | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Responsibility | High | Medium | Low | High |

| Appraisal tendency | Perceive events as unpleasurable, predictable, under human control, and prompted by others | Perceive events as unpleasurable, unpredictable and under situational control | Perceive events as pleasurable and prompted by the self | Perceive events as pleasurable, unpredictable, and prompted by others |

| Impact on relevant outcome | Influence on risk perception | Influence on attribution | ||

| Perceive situation to be low risk and optimistic; increased risk taking behaviours | Perceive situation to be high risk and pessimistic; reduced risk taking behaviours | Perceive self as responsible; increased confidence | Perceive others as responsible; increased attention on the situation | |

Criticism: Emotions are dynamic processes, rather than stable states.[16] Existing methods are unable to apply the 6 dimensions for all emotional experiences. Further studies are required to explore the relationship between emotions and different dimensions more in-depth.[17]

|

Appraisal is the mental evaluation of the significance of an event in regard to an individual's wellbeing, this includes the goals, needs, beliefs, and attachments to an item or a personal relationship (see Figure 4). This is summarised by the:[18][10]

- Feeling state

- Sense of purpose

- Expressive signals

- Coping behaviours

Possible actions are outlined while the individual collects information for alternative options. Future events and other relevant circumstances are identified and evaluated.[19] The individual then compares the possible outcomes associated with different behaviours, using their best judgment to identify one that is the most appropriate. Appraisal can also be a learning process; after making a decision, one can evaluate how well it went, and potentially use a similar approach for future practices (see Table 4).[14]

Table 4 Appraisals and emotions

| Feeling state | Fear | Anger | Disgust | Sadness | Interest | Joy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Threat | Interference with goal pursuit or unjust treatments | Spoilt food | Loss, separation,

and failure |

Novelty | Goal progress and attainment |

| Sense of purpose | Protect the self and avoid harm | Overcome barriers or seek revenge | Repulse | Reverse the situation back to it's original state | Explore new areas to gain information | Sooth, engagement |

| Expressive signals | High pitch and strained tone | Frown

Clenched jaw and fist |

Wrinkled nose

Raised cheeks and upper lip |

Frown

Pouted lips |

Eye contact

Raised eyebrows Dropped jaw |

Open palms

More physical contact |

| Coping behaviour | Flee the scene | Punch the wall | Throw away the food | Crying | Lean forward | Cheers |

Appraisals can activate 2 elements that are critical for decision-making.

- Appraisal tendency: it will direct attention, memory, and judgment to cope with the current event until the emotion-eliciting problem is resolved.[19]

- The carry-over effect: an emotion's may be strong enough to impact the cognition subconsciously through perception, beliefs, interpretation, attitude, and reasoning towards a seemingly unrelated subsequent event.[14]

|

A stranger begins to approach Joanna. After noticing, Joanna immediately appraised the meaning of this approach by evaluating obvious characteristics of the person approaching (e.g., gender, facial expression, pace of approach), and relevant memories of approaching others, or being approached. Due to the negative experiences she had in the past, she experienced fear. Joanna ran into a nearby café until her bus arrived. Later that day, she called in sick for her friend's birthday party. |

Drawing from the case study, Joanna's appraisal tendency was to flee the scene and avoid conversations with a stranger. The carry-over-effect resulted her in cancelling a future event that requires social interactions. In the end, the action of approaching itself does not explain the quality of Joanna's emotional reaction; rather, it is the her expectation of how this approach will go that affects her wellbeing[20].

Though scientific, further studies are needed to understand the unique pattern among multiple appraisal dimensions, and the specific length of the carryover effect. [21] |

Quiz

Choice and basic emotions

[edit | edit source]

The decision making process can be heavily impacted by emotional states, environment or personality influences (see Figure 5).[5]

Joy

[edit | edit source]Related to pleasure, engagement and meaningful antecedents. This can mean desirable things such as winning an award, or making a new friend.[22]

- Promotes positive evaluations of other people, objects, or events, facilitating one's willingness to engage in social situations and strengthen relationships.[23]

- Counters distressing or aversive emotions to protect mental health.[4] The positive experiences associated with joy can enhance confidence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation to seek further rewards.[3]

- It broadens attention and cognition to better avoid risk, and promote more prosocial and creative problem-solving behaviours.[23]

- It increases the individual's ability to focus on long-term consequences instead of immediate satisfaction.[3]

|

After speaking with his therapist, Zac gained more confidence in his abilities, and an optimistic outlook for his future. He found the conversations to be meaningful, and decided to make healthier choices in both his personal and professional life by drinking less alcohol and volunteering for more difficult tasks. |

Anger

[edit | edit source]Can arise from interruptions when pursuing a goal, or unfair experiences; for example, threat, provocation, and non-cooperative responses.[24] The individual is certain that another person was responsible for this negative feeling, has a desire to change the situation for the better, even if it means through destructive ways.[25]

- The individual enters a fight-or-flight state, where the body prepares physical and mental resources for them to defeat the 'enemy'.[24]

- With repetitive exposure to a certain stimulus, anger can become automatic, meaning minimal things can trigger a big reaction. This can influence an individual’s response to other events, without any awareness of the connection.[26]

- There is unrealistically high confidence of who is to blame, and how to change the outcome.[11] This can lead to narrow, self-focused way of interpreting the situation (which isn't always correct), resulting in preferences for self-serving, impulsive, risky, and unethical behaviour (e.g., seeking revenge).[24] The individual may focus more on punishing, rather than problem-solving.

|

Kate doesn't have a good relationship with Ebony, her co-worker; they are both competing over the same promotion. Kate overheard Ebony conversing with their boss. Later that day, the boss decided to promote Ebony. Kate is suspicious that Ebony may have been bad-mouthing her, and decides to take revenge by slashing her tires. |

Fear

[edit | edit source]It arises in response to identifiable or anticipation of vulnerability, threat or harm; those feelings can be real or imagined, physical or psychological, often caused by the individual's lack of coping ability.[26] This can include fear for insects, horror movies, feelings of being followed in a dark environment, and so on.

- The body alerts the individual and prepares for protection, such as providing warning signs (gut feeling), the fight-or-flight response, and facilitate learning for new coping responses to avoid future encounters with that stimulus.[24]

- When the ‘flight’ option is inaccessible, fear generates anxiety. Anxiety then create cognitive overload, reduce performance on cognitively demanding tasks.[9] It can impair the quality of judgment due to certain brain regions shutting down.[8]

- The individual can develop an external locus of control.[9] Opposite to anger, they believe the events are unpredicted and uncontrollable. This can lead to individuals have a pessimistic judgement about the future, avoid overpowering stimuli and reduce risky behaviours.[8]

|

[[

File:Phantom Open Emoji 1f640.svg|Phantom_Open_Emoji_1f640|30px]] Case study 5Keira is worried about the side effects of her anti-depressants. She refuses to take them even though it was suggested by her GP. |

Sadness

[edit | edit source]Sadness often happens after experiences of separation, loss, helplessness or failure.[26]

- It promotes for compensatory actions, in hopes to restore the environment back to its original state, or facilitate personal reflection or reconsideration of plans and goals to accommodate for the loss.[27]The loss of something valued (lack of control) leads to an unconscious sadness-consumption effect e.g., pay more to acquire new goods, more consumption of tasty, fattening, unhealthy food products than usual. The effect helps to create a sense of control due to the increased choice, and temporarily attenuate sadness’ effect.[25]

- Same as fear, it can lead to pessimistic thinking and promote the development of an external locus of control.[25] The brain downplays the value of an achievement or a reward, and focuses on more self-defeating behaviours e.g., rumination, irrational buying, overthinking[27]. This increases the likelihood of developing depression[26].

- The individual may find themselves more interested in new products, experiencing more difficulty making decisions, or unable to imagine how differently things could turn out.[12][26]

|

Beth's favourite celebrity couple just broke up. After binge eating a tub of ice-cream, she thought to herself "If those two broke up, there will be no hope for a happy and lasting relationship!"

|

Are emotions bad for the decision-making process?

[edit | edit source]There are assumptions where emotions often have a negative relationship with quality decisions; however, it all depends on how the emotional information are used.[1] The ability to generate appropriate responses relies on emotional information. This means, it will not be possible for someone to decide without the support of emotions.[28] Studies suggest, the way a person experiences, handles, and use their emotions can determine it's helpfulness to the decision-making process.[1] High performance typically encourages when an individual has sufficient understanding of their emotional states, and keeps it from interfering with their ability to think rationally; thus, emotion regulation tools may be useful to develop a coherent and effective channel of communication within the self, to enhance the decision-making process (see table 5).[7]

| Tools | Definition and impact | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Time delay | To avoid direct impact of emotional states on decision-making, it may be helpful to give the brain some time to rationalise the situation and bring the intense emotions back to baseline.[29] This provides more options for the individual to decide how to act, what is appropriate, and state facts instead of using potentially harmful emotional words.[28] | Stepping back and take a walk |

| Reappraisal | Reframe the event. A stressful experience can be reconstructed as meaningful, which motivates for emotional growth.[29] | From "I messed it up" to "I have learnt my lesson and will know how to better approach it next time." |

| Awareness | Increasing awareness of emotions reduces misattribution.[28] Instead of avoiding or suppressing the emotional experience, it should be identified and dealt with. Appraisal tendencies will be deactivated when the individual becomes more cognitively aware of the decision-making process.[29] | Regular journaling and self-reflections |

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Theories (appraisal theories, affect-as-information model, valence-based approach) and research on choice and emotion are important in order to understand the conscious or unconscious influence on an individual's cognition and physical experiences. This includes bodily reactions, facial expression, appraisal, attention, goal, content and depth of thought.[2] Emotions do not cause bad choices, but rather how people decide to use it.[28] There are emotion regulation tools that can enhance emotional management and perceived choice; when used well, it becomes possible to optimise the decision making process, and enhance the individual's wellbeing.[7] In short, raising awareness of an emotion, and its impact on your decision-making process can be beneficial for future outcomes, whether if its personal or social.[20]

|

Thinking back..

Going back to the first case study, if you were X (who had their belongings stolen), what do you think would be the best way to approach Y about this situation?

|

See also

[edit | edit source]- Emotions in decision making (Wikipedia)

- Choice overload: What is choice overload? What is the optimal amount of choice? (Book chapter, 2022)

- Glasser’s choice theory: What is choice theory and how can it be applied to improve motivation and emotion? (Book chapter, 2019)

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ahsan Khodami et al., 2021

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mirabella, 2018

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Lerner et al., 2015

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Taquet et al., 2016

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bruch & Feinberg, 2017

- ↑ Huff & Johnson, 2014

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Wang et al., 2020

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Scherer et al., 2022

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Wake et al., 2020

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Izard, 2009

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kauscheke et al., 2019

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Citron et al., 2014

- ↑ Lerner et al., 2015

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Roseman, 2013

- ↑ Smith & Ellsworth, 1985

- ↑ Gneezy et al., 2014

- ↑ Smith & Ellsworth, 1985

- ↑ Gu et al., 2019

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Moors, 2020

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Kozlowski et al., 2017

- ↑ Gu et al., 2019

- ↑ Seligman, 2002

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Lei, 2022

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Lerner & Tiedens, 2006

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Compare et al., 2014

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Masters et al., 2023

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Kempt et al., 2014

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Gneezy & Imas, 2014

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Price & Hooven, 2018

References

[edit | edit source]- Ahsan Khodami, M., Hassan Seif, M., Sadat Koochakzadeh, R., Fathi, R., & Kaur, H. (2021). Perceived stress, emotion regulation and quality of life during the Covid-19 outbreak: A multi-cultural online survey. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2021.02.005

- Bruch, E., & Feinberg, F. (2017). Decision-making processes in social contexts. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053622

- Citron, F. M. M., Gray, M. A., Critchley, H. D., Weekes, B. S., & Ferstl, E. C. (2014). Emotional valence and arousal affect reading in an interactive way: Neuroimaging evidence for an approach-withdrawal framework. Neuropsychologia, 56, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.01.002

- Compare, A., Zarbo, C., Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Marconi, C. (2014). Emotional regulation and depression: A potential mediator between heart and mind. Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology, 324374, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/324374

- Gneezy, U., Imas, A., & Madarász, K. (2014). Conscience accounting: Emotion dynamics and social behavior. Management Science, 60(11), 2645–2658. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1942

- Gu, S., Wang, F., Patel, N. P., Bourgeois, J. A., & Huang, J. H. (2019). A model for basic emotions using observations of behavior in drosophila. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(781). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00781

- Huff, S., Johnson, A. (2014). Clicking through overload: When choice overload can actually increase choice. J Direct Data Digit Mark Pract 16, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2014.37

- Izard, C.E. (2009). Emotion theory and research: Highlights, unanswered questions, and emerging Issues. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 1–25. https://dio.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163539

- Kauschke, C., Bahn, D., Vesker, M., & Schwarzer, G. (2019). The role of emotional valence for the processing of facial and verbal stimuli—positivity or negativity bias? Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01654

- Kemp, E., Kennett-Hensel, P. A., & Williams, K. H. (2014). The calm before the storm: Examining emotion regulation consumption in the face of an impending disaster. Psychology & Marketing, 31(11), 933–945. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20744

- Kozlowski, D., Hutchinson, M., Hurley, J., Rowley, J., & Sutherland, J. (2017). The role of emotion in clinical decision making: An integrative literature review. BMC Medical Education, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1089-7

- Lei, X. (2022). The impact of emotion management ability on learning engagement of college students during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.967666

- Lerner, J.S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P. and Kassam, K.S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 799–823.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043

- Lerner, J.S. and Tiedens, L.Z. (2006). Portrait of the angry decision maker: How appraisal tendencies shape anger’s influence on cognition. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 115–137.https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.515

- Masters, N., Lloyd, T., & Starmer, C. (2023). Do emotional carryover effects carry over? Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4527014

- Mirabella, G. (2018). The weight of emotions in decision-making: How fearful and happy facial stimuli modulate action readiness of goal-directed actions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01334

- Moors, A. (2020). Appraisal theory of emotion. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_493

- Price, C.J. and Hooven, C. (2018). Interoceptive awareness skills for emotion regulation: Theory and approach of mindful awareness in body-oriented therapy (MABT). Frontiers in Psychology, 9(798). doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00798.

- Roseman, I. J. (2013). Appraisal in the emotion system: Coherence in strategies for coping. Emotion Review, 5(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912469591

- Scherer, K. R., Costa, M., Ricci-Bitti, P., & Ryser, V.-A. (2022). Appraisal bias and emotion dispositions are risk Factors for depression and generalized anxiety: Empirical evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.857419

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Free Press.

- Smith, C. A., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1985). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(4), 813–838. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.4.813

- Taquet, M., Quoidbach, J., de Montjoye, Y.-A., Desseilles, M. and Gross, J.J. (2016). Hedonism and the choice of everyday activities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(35), 9769–9773. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519998113

- Wake, S., Wormwood, J., & Satpute, A. B. (2020). The influence of fear on risk taking: a meta-analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 34(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1731428

- Wang, X., Zheng, Q., Wang, J., Gu, Y., & Li, J. (2020). Effects of regulatory focus and emotions on information preferences: The affect-as-information perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01397

- Xing, C. (2014). Effects of anger and sadness on attentional patterns in decision making: An eye-tracking study. Psychological Reports, 114(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/10.2466/01.04.pr0.114k14w3

External links

[edit | edit source]- Emotions & decision-making: The neuroscience(Feelings Matter)

- The psychology behind irrational decisions(TED-Ed)

- DERS-16 emotional regulation test (The Attachment Project)

- DBT skills: Emotion regulation and acceptance (Self-Help Toons)

- How to manage your emotions (Ted-Ed)