Motivation and emotion/Book/2022/Natural disasters and emotion

How do people respond emotionally to natural disasters and how can they be supported?

Overview

[edit | edit source]My Family, Fire and Fear

When I was eight I experienced my first ever natural disaster, the 2003 Canberra Bushfires. When the fire arrived I had an all encompassing feeling of terror, I didn’t fully understand what exactly was going on but I knew I was in danger. My dad however was focused and determined to get our family to safety. We didn’t know where my mother was as we were arriving back from a holiday when the fire hit. My mum chose to stay at home to look after my younger brother who was only a baby. When we arrived to the street I lived on, the entire suburb was ablaze. My dad told me and my sister to stay in the car while he went to see if my mum was still inside our home. Shielding his eyes he dashed past the flames coming from the house at the end of the street, a moment of bravery that he says to this day was his most fearful moment.

Thankfully he survived, he couldn’t find my mum or brother, so he took us to our grandparents house assuming my mum would have gone there to make sure they were okay. He wasn’t wrong, my grandmother said she did come here but they sent her to the evacuation centre which was set up at a local college. They didn’t go with her because the fire was heading towards their house and they wanted to grab a few things. My dad refused their insistence he go as well to the evacuation centre and instead stayed to help them.

We made it to the evacuation centre, and there were crowds of people, all talking to one another. The evacuation centre personnel didn’t seem to know what to do with everyone, but looking back on it, we kind of just all automatically worked together to get comfortable that night. People were already helping one another to find family members, and a lovely lady helped us find my mum. Although she was covered in ash, she was alive and well. I haven’t had many tears of joy in my life but that moment was one of them, when we all hugged as a family.

Fast forward to 2019, once again disaster had struck. The southern Canberra suburbs were in the line of the Orrorall Valley fire. People were being readied to evacuate should the need arise, yet at no point did I feel afraid for my safety, but I was very afraid for my dad's safety. He was no longer the young man able to run into the flames for others. I spent that entire week at his place ensuring I was ready to help if needed.

The above story about my families experiences with bushfires possibly seems a bit strange. There is the usual emotions one would expect from a disaster—fear. Yet that fear isn’t just about ones own survival, there’s more to the fear both me and my family experienced. Theres also feelings of joy in the story, how could a traumatic experience like a disaster illicit the emotion of joy? As we explore the psychology of emotions relating to natural disasters, hopefully you will see there is explanations for these emotions.

Additionally it is crucial to understand that although emotions during disasters are experienced individually, they are rarely experienced alone. Natural disasters impact individually but also impact whole communities of people. The harsh reality is that more people and communities will experience natural disasters, as they are only increasing due to climate change (World Meteorological Association, 2021). Now is the best time to understand the emotions in relation to disasters. This chapter draws heavily from studies of survivors of natural disasters to describe the emotions at play, as well as providing evidence based methods for supporting peoples emotions when disaster strikes.

Before we even explore the emotions, it is a good idea to gain an understand the stages of a disaster in an emotional context. According to Myers & Wee (2005), emotions and when they occur during a disaster can be best understood when dividing a disasters lifespan into different sections. Those sections being the pre-disaster, Impact, honeymoon, disillusionment and restructuring. Keep these phases in mind as you read about the emotions and how to support yourself and others with their emotions

Phases of disaster recovery

[edit | edit source]

Pre-disaster Phase: This is the phase when knowledge of a disaster is present and individuals act accordingly to prevent harm, this phase is often logic driven based on advice or prior experience

Impact phase: This is the phase when the disaster hits and individuals are most likely to experience purely survival minded emotions

Honeymoon phase: this is the phase where relief is experienced and safety is commonly found following the impact of the disaster, following this stage with the right conditions some individuals can go on to restructure their understanding of the experience in a healthy manner. If they don’t have the right conditions they become disillusioned

Disillusionment phase: This is when individuals feel distressing emotions and franticly search for ways to cope, this phase often results in negative outcomes unless individuals are provided the right tools to cope positively. This phase can lead people to re-experience the impact of the disaster, even when they are safe

Restructuring phase: This is when individuals begin the path of acceptance, and rebuild their life and communities.

How do people react emotionally to natural disasters?

[edit | edit source]It is a common assumption that emotions relating to natural disaster are mostly fear-based, and pass when the disaster subsides. While it is true that fear is one of the most common emotional reactions to a disaster, it is by no means the only one. Further, fear can have a multitude of different presentations in the context of a disaster. Emotions are not a singular event when it comes to traumatic life experiences, multiple emotions can occur simultaneously, and at different times during the course of a disaster.

Fear

[edit | edit source]Given fear is one of the most commonly associated emotions connected with mass threats like natural disasters (Espinola, et al. 2016), it perhaps is the best emotion to start exploring. Fear is one of the core emotions, it is often considered to be negative; however fear serves its purpose by encouraging us to find safety from a threat (Steimer, 2002). One of the most commonly used definitions of fear is that it is an emotion in response to a known adverse environmental stimuli, both before the stimulus is present and/or within its presence (Steimer, 2002). What is important to remember with fear is that it is a known threat, when we experience fear we are aware of what the threat is or might be.

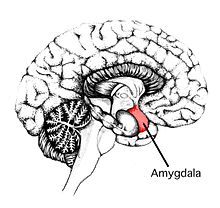

A good place to start with fear is to look at it from inside the brain. There is a structure in the brain called the amygdala, its responsible for recognising threats and relaying messages to other areas of the brain (Öhman, 2005). This is done to begin the process of causing a bodily reaction that culminates in the fight, flight or freeze response. The amygdala upon recognising a threat sends a signal to the hypothalamus, which then relays this signal to the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the blood stream (Grey & Bingaman, 1996). ACTH’s main function is to increase epinephrine production from the adrenal gland. Epinephrine plays an important role in enabling the bodily requirements for the immediate fight, flight or freeze response (Kozlowska, et al. 2015).

During the fight, flight or freeze response the parasympathetic nervous system prioritises bodily functions typically needed for survival (McCory, 2007). Muscles become tense, heart rate and breathing increases and digestion slows; this aids us in automatically doing what or body decides needs to be done in order to ensure our survival in the face of something that has caused the fear. During a disaster scenario it is not uncommon to hear of people talking about being so afraid they ran faster than they thought they ever could, pulling off feats of strength they didn’t know they could do or completely being frozen by fear. This all comes down to the brain and how it processes fear in the face of an imminent threat to our survival.

It is understandable given how our body reacts to fear to think it is only about ones own safety when presented with a threat. This may not be entirely accurate when it comes to disasters. In 2016-2017, central Italy was impacted by earthquakes, hundreds of people lost their lives and many structures were destroyed (Mollaioli, et al. 2019). A study by Massazza, Brewin & Joffee (2021) looking into the ‘peritraumatic reactions’ or the thoughts, feelings and behaviours due to trauma found survivors of Italys earthquakes had an interesting experience with fear. The studies participants were asked in an interview setting to describe how they felt during the impact of the disaster; 78 percent of the 104 participants mentioned feeling fear for the safety of others and 70 percent mentioned feeling fear for their own safety. This shows that fear during a disaster may not just be an emotional response about ones own wellbeing but also the wellbeing of others.

Thought Time: Lingering fear

With the Italian earthquake study they also found that majority of the participants were struck with continual increased general fear and anxiety. When we experience a major threat to ourselves and others the fear and anxiety we experience can sometimes become ongoing even when the threat passes. The amygdala is responsible for recognising something fearful and readying our response, yet it serves another purpose. A study by Duvarci, Bauer & Pare (2009) found that aside from sending signals to hormone response areas of the brain the amygdala also sends messages to an area known as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. They found that the bed nucleus is critical for long term generalised emotional arousal, the more significant a message is sent between the amygdala and the bed nucleus the more likely one will experience ongoing general fear that something may occur.

Think of a time you have experienced intense fear, did that feeling linger? If it did, how long did it last? And was that fear the same intensity as what you originally experienced?

Young adults across cultures have been observed to experience less fear of being harmed by natural disasters than older adults or young children. A study of Macedonian, Turkish and Serbian young adults found a markedly increased fear for others than themselves pre-disaster, specifically there was fear across all three countries for their parents and childrens safety (Cvetkovic, Ocal & Ivanov, 2019). This could be an example of ‘sandwich generational squeeze’ which is the name for the phenomenon that is young to middle age adults feeling compelled to attend the needs of both their elderly parents as well as their own children (Brody, 2003). In a disaster scenario, as the need is one relating to survival, it’s possible the fear for the survival of the elderly and children outweighs the feelings of fear for ones own survival.

Sadness

[edit | edit source]Sadness is also common during times of disaster, often sadness presents in the honeymoon and disillusionment phases of a disasters. Once the threat has abated, even with the knowledge it wasn’t their fault, individuals can experience intense sadness (Izard, 1991). One of the reasons this could be is due to an individual having time to assess their loss in the aftermath of the disaster. What can happen following this assessment and experiencing the accompanying sadness, an individual may attempt to regain some control as a means to cope with their loss (Vandervoort, 2001). This was seen at play with hurricane Katrina; the higher the loss the individual experienced after the storm the more they would drink or smoke in an effort to not experience intense feelings of sadness (Flory, et al. 2009). There was even increased instances of addiction amongst the impacted communities following Katrina (Beaudoin, 2011).

It is not just vices such as alcohol people use to avoid experiencing sadness and loss of control. Researchers looking at consumption and buying habits post-Katrina found a significant number of the population were buying needless items directly after the disaster (Sneath, Lacey & Kennett-Hensel, 2009). Participants of the consumption study struggled to explain why they purchased so many items but a common reason put forward was often that they didn’t like seeing all their possessions destroyed and feeling incredibly sad even distressed because of this. One of the participants impulse bought because they felt numb due to sadness and wanted to feel more positive. Impulse buying has an emotional component (Eysenck et al,.1985), and its driven in a disaster scenario by a need to restore how we felt prior to the disaster, or reduce the emotional impact in the moment of experiencing loss.

Anger

[edit | edit source]Anger arises when there is something in the way of a goal we care about, sometimes this can be a small event, or it can be massive like a disaster destroying your community (Stephens & Groeger, 2011). Anger is most often seen much later following a disaster, usually in the disillusionment and restructuring phases. The anger is commonly directed towards failings on a community level. Anger makes individuals far more likely to recognise injustices (Keltner, Ellsworth & Edwards, 1993); when local authorities fail to provide the needs of a community during a disaster, no matter how inevitable, it is often responded to with aggression. Anger is also a precursor to change and adaptation, it sends the message that this injustice will not be accepted again. As an emotion, anger is less about motivating ourselves and more about ensuring others are motivated to do better.

While we think of anger as a negative emotion, in the aftermath of a disaster it actually serves a positive purpose. Anger in the wake of a disaster can lead to collective action by a community, this action can even involve individuals who are not impacted by the disaster (Vestergren, Uysal & Tekin 2022). This collective action occurs mostly due to anger from the disaster shedding light on the disproportionate effects on minority or vulnerable groups (Templeton, et al. 2020). Members of the community may then band together in anger and frustration at the injustice, this creates a sense of shared identity and increased community connection (Cocking, et al., 2009). This spurs change, and is vital in building a more connected and disaster resilient community in the future.

Thought Time: Common Fate

There exists an idea amongst disaster literature about ‘common fate’, common fate explains why we don’t take an every man for themselves approach to a disaster, instead we often turn towards one another even with little knowledge of who the other person is. Drury, et al. (2010) interviewed groups of individuals who experienced various disasters and nearly all of the groups spoke of the sense of connection and shared support during each of the disasters. The researchers suggest the reason for this comes down to how we recognise a common fate, and that all other ideas of who an individual is dissipates, we then view each other on the same social level. As we have seen; fear, sadness and anger are never just about ourselves during times of disaster. Some element of our emotions during times of disaster are involving others.

Do you think ‘common fate’ may provide a possible reason why during times of natural disaster there’s almost always emotion involving others?

Joy

[edit | edit source]Joy is just as common as negative emotions during a disaster, during the honeymoon phase of the disaster it is one of the positive emotions people experience most. In El Salvadore, during the days following a devastating earthquake, survivors in the evacuation centre reported experiencing joy (Vazquez, et al. 2005). The adult survivors spoke specifically about the joy of being alive, and of their family members surviving. They also spoke about being given the chance to connect to the community and that increased the shared sense of joy amongst the adults. The children within the centre spoke specifically of the joy relating to the positive experiences at the evacuation centre, as well as being given time to spend with their peers.

Social media is also an effective way to examine emotions in real time during the course of a disaster. Social media posts during the Kerala floods in India showed that overall there was an increase in positive sentiment, such as joy, within tweets after the immediate impact of the disaster, as opposed to negative sentiment during the impact (Mendon, et al. 2021). Joy can actually enable us to broaden our perspectives (Fredrickson, 1998); so the joy at spending time with family may have broadened individuals views on the impact of the disaster from a negative to a positive experience. The social media posts and evacuation experiences could also indicate people engaging in reappraisals, or reshaping the experience to a more positive emotion (John & Gross, 2004). This would aid another effect joy has, which is its ability to sooth our overall experience (Levenson, 1999), even when that experience is a traumatic one.

Quiz

[edit | edit source]

How can those affected be supported?

[edit | edit source]Now that we know the different types of emotions, its time to look at how we can support peoples emotional well being over the course of a disaster. There’s no sure-fire right or wrong way to support yourself or others to cope. Some ways may work better than others, but it all comes down to the individual. To understand ways of supporting yourself and others we will break down the different potential methods by the different phases of the disaster.

Pre-disaster

[edit | edit source]Effective and clear communication is key in this phase, this is not just about communicating the best methods for preparation but also about communicating information on what the disaster even is. It's a good idea to encourage people you know, and even yourself to read local emergency services communications on the disaster. The more individuals understand exactly what they will be facing the more likely they are to experience reduced fear and still act in a manner which best supports their survival (Bonanno & Gupta, 2012). For vulnerable groups communication needs to be adapted to best support their situation, in some cases using plain direct language will be important or providing information directly instead of via computer devices (Howard, Bevis & Blackmore, 2017),

Reach out to your elderly family members, and vulnerable people you know. If you are worried about their safety, work with them on setting up an evacuation or emergency plan before a disaster strikes. This is particularly important for supporting those you know with a disability, or increased needs when the disaster impacts. This will help to calm any fears you may have for their safety and enable you the ability to prioritise your own emergency plan.

Thought Time: Disaster ready

With your disaster plan, its a good idea to consider the following:

-What you plan on taking from your residence?

-Do you have your id documents in one spot?

-Do you have any items that cant be replace that you could easily transport?

-What medications, medical equipment or other health related items you will require?

-Who are your emergency contacts?

-What to do about your pets, where will they stay, how will you transport them?

BUT, you should also consider these things:

-What is something that helps keep you calm when you are stressed?

-Do you know already how you react in high intensity situations? have you written this down so family members or emergency personnel can easily understand how you are behaving?

Your disaster plan should also incorporate your mental wellbeing, it cant just be about your physical safety!

Impact phase

[edit | edit source]Supporting emotions during the impact phase can only commence once an individual has found safety. Governments ensuring adequate facilities for shelter is crucial, this also means adequate facilities for vulnerable communities such as the elderly and those with disabilities. Supporting vulnerable groups has been identified as a key improvement area cross-culturally in impact disaster response (Kako, et al. 2020). If not already implemented emergency personnel should be made aware at a local level of any vulnerable members of the community who may require additional support. Disability services should engage with their clients on how the evacuation, and shelter process is going to work and what supports will be available.

Once adequate safety is obtained, individuals have time to asses their situation, this is when negative emotions like sadness and fear for others are most likely to start arising. Use the time while sheltering to speak with someone you trust, vocalising how you are feeling can help to alleviate some of the fear. Reduce over usage of news material, aim to only access news material that relates to your specific situation (like emergency broadcasts), over indulging in news can increase fear (Bodas, et al. 2015). This also applies to social media, aim to only use it to reach out to converse with family and friends instead of scrolling for more information on the unfolding disaster.

Honey-moon phase

[edit | edit source]This phase is the best time to build and encourage positive habits in the wake of the disaster. Firstly alcohol and other vices should be avoided as a means of coping, as we saw above this can lead to addiction. If you are going to engage in addictive substances it is best to do it in a positive social situation and place a limit on yourself.

Another method for supporting your emotional wellbeing is to engage in a regular routine, this creates a sense of normalcy even in the absence of normal. This could be as simple as setting a specific time to get up each morning, or creating a meal plan to follow. Something that is consistent and regular will help to reduce lingering feelings of fear by increasing a sense of ‘normal’ (Bonnano, et al, 2007)

Lastly during this phase, avoid making big life decisions, when we have gone through a period of emotional turmoil we don’t have the best judgment (Ross III & Coambs, 2018 ). If a big life decision does present itself, allow or request time to consider it, don’t be afraid of explaining the reason you need time. As you saw above its common for others to understand and accept that you will be struggling for abit given the situation. Its best to not add any additional stress during the honeymoon phase.

Disillusionment phase

[edit | edit source]If you feel your emotions becoming overwhelming or increasingly negative post-disaster you are likely in the disillusionment phase. For supporting emotions during this phase it's all about social connection. As with the impact phase, voicing how you feel to someone you trust can alleviate the immediate pressure or distress you may feel. For young adults and teenagers this is particularly important, as increased negative emotions during this phase can turn towards criminality (Nuttman-Shwartz, 2019). With teenagers if their emotions are leaning towards negative coping strategies, It may be a good idea to include them in simple community rebuilding tasks as an effective way of creating purpose, social connection and providing a sense of accomplishment. Teenagers are highly adaptable in turning negative emotions relating to disasters into positive community action (Nuttman-Shwartz, 2019)

For adults support groups are a good way to meet others in similar situations and to engage in emotional reciprocation. When we share how we feel with others who understand the situation we often gain new perspectives and feel a reduction in negative emotions, this is known as situation modification (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). This is also a perfect time to practice reappraisals, which as we saw above in the section on joy, is when we change how to think about an emotion eliciting situation to reduce its impact (John & Gross, 2004). There are many different avenues in regards to reappraisals, but the simplest is to find a single positive, no matter how small and remind yourself of it whenever you feel distressed. Instead of ‘The storm destroyed everything’ reframe it as ‘Yes the storm destroyed my home, but my family are alive’.

Socialisation during this phase isn’t just a net positive for teenagers and adults but also young children. A study by La Greca, et al (2013) was conducted looking at children’s distress and recovery trajectories following the devastating Hurricane’s Andrew and Katrina. The study found that overall children experience a similar increase resilience level post-disaster compared to adults; these resilient children in the immediate aftermath of the disaster were encouraged to engage heavily in socialisation. Children that didn’t engage in socialisation developed negative emotional regulation strategies and their recovery trajectory didn’t lend its-self towards resilience. It doesn’t need to be complicated, simply allowing kids to spend time playing with each other has huge benefits on emotional regulation and recovery trajectories.

If you don’t feel confident being apart of a support group or talking to others, you could also turn to a creative pursuit to vent how you feel. Art is an incredible way of exploring how you feel without the need to meet with others (Reynolds, et al. 2000 ), it doesn’t need to be perfect or complex, a simple pen and paper can do. If your emotions become to intense and upsetting, you could use the creative pursuit to distract yourself from these emotions instead, drawing is considered one of the go to methods of distraction (Dalebroux, Goldstein & Winner, 2008).

Reconstruction phase

[edit | edit source]This phase is when you move on from the disaster, moving on doesn’t mean the negative feelings of fear, sadness and anger go away, it simply means they become more manageable. This is a perfect time to engage in community rebuilding pursuits or collective actions to vent any anger at social issues raised by the disaster. Engage in supporting local rebuilding and disaster support groups like the red-cross. You may also want to use the reconstruction as a time to see if a memorial of the disaster and of lives lost will be established. Communities which create spaces of remembrance often gain a good deal of appreciation, cohesion and acceptance following the disaster (Maddrell & Sidaway, 2010). You could even just organise time with friends and family to conduct your own private acknowledgement of the disaster.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]We have reached the end of our exploration of disasters and emotions, there’s several key take aways I hope you have recognised. The first is that emotions during disasters are not singular, we can experience many emotions over the life-span of the disaster. The next takeaway; in the event of a disaster, you will never be alone in how you feel. In fact there is a high chance you will hold emotions for family members, or find support in dealing with your emotions from those close to you or potentially even from complete strangers. The last takeaway; although disasters have a habit of upheaving our whole life, there is always positive moments to be had. Though I sincerely hope you never experience a natural disaster, if you do, I hope you can recognise why you experience certain emotions and are well equipped to support these emotions to a positive outcome.

See also

[edit | edit source]

References

[edit | edit source]Bodas, M., Siman-Tov, M., Peleg, K., & Solomon, Z. (2015). Anxiety-inducing media: The effect of constant news broadcasting on the well-being of Israeli television viewers. Psychiatry, 78(3), 265-276.

Bonanno, G. A., & Gupta, S. (2012). Resilience after disaster.

Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75 (5), 671. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671

Brody, E. M. (2003). Women in the middle: Their parent-care years. Springer Publishing Company.

Cocking, C., Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2009). The nature of collective resilience: Survivor reactions to the 2005 London bombings. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 27(1), 66-95.

Cvetković, V. M., Öcal, A., & Ivanov, A. (2019). Young adults’ fear of disasters: A case study of residents from Turkey, Serbia and Macedonia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 35, 101095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101095

Dalebroux, A., Goldstein, T. R., & Winner, E. (2008). Short-term mood repair through art-making: Positive emotion is more effective than venting. Motivation and Emotion, 32(4), 288-295.

Drury, J., Cocking, C., & Reicher, S. (2009). Everyone for themselves? A comparative study of crowd solidarity among emergency survivors. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(3), 487-506.

Duvarci, S., Bauer, E. P., & Paré, D. (2009). The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis mediates inter-individual variations in anxiety and fear. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(33), 10357-10361. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2119-09.2009

Espinola, M., Shultz, J. M., Espinel, Z., Althouse, B. M., Cooper, J. L., Baingana, F., ... & Rechkemmer, A. (2016). Fear-related behaviors in situations of mass threat. Disaster health, 3(4), 102-111. doi: 10.1080/21665044.2016.1263141

Eysenck, S. B., Pearson, P. R., Easting, G., & Allsopp, J. F. (1985). Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personality and individual differences, 6(5), 613-619.

Flory, K., Hankin, B. L., Kloos, B., Cheely, C., & Turecki, G. (2009). Alcohol and cigarette use and misuse among Hurricane Katrina survivors: psychosocial risk and protective factors. Substance use & misuse, 44(12), 1711-1724. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080902962128

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions?. Review of general psychology, 2(3), 300-319.

Gray, T. S., & Bingaman, E. W. (1996). The amygdala: corticotropin-releasing factor, steroids, and stress. Critical Reviews™ in Neurobiology, 10(2).

Howard, A., Agllias, K., Bevis, M., & Blakemore, T. (2017). “They’ll tell us when to evacuate”: The experiences and expectations of disaster-related communication in vulnerable groups. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 22, 139-146.

Izard, C. E. (1991). The psychology of emotions. Springer Science & Business Media.

John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of personality, 72(6), 1301-1334.

Kako, M., Steenkamp, M., Ryan, B., Arbon, P., & Takada, Y. (2020). Best practice for evacuation centres accommodating vulnerable populations: a literature review. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 46, 101497.

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of personality and social psychology, 64(5), 740.

Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L., & Carrive, P. (2015). Fear and the defense cascade: clinical implications and management. Harvard review of psychiatry.

La Greca, A. M., Lai, B. S., Llabre, M. M., Silverman, W. K., Vernberg, E. M., & Prinstein, M. J. (2013, August). Children’s postdisaster trajectories of PTS symptoms: Predicting chronic distress. In Child & youth care forum (Vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 351-369). Springer US.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.

Levenson, R. W. (1999). The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 13(5), 481-504.

Maddrell, A., & Sidaway, J. D. (Eds.). (2010). Deathscapes: Spaces for death, dying, mourning and remembrance. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd..

Massazza, A., Brewin, C. R., & Joffe, H. (2021). Feelings, thoughts, and behaviors during disaster. Qualitative Health Research, 31(2), 323-337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320968791

Mendon, S., Dutta, P., Behl, A., & Lessmann, S. (2021). A Hybrid approach of machine learning and lexicons to sentiment analysis: enhanced insights from twitter data of natural disasters. Information Systems Frontiers, 23(5), 1145-1168.

Mollaioli, F., AlShawa, O., Liberatore, L., Liberatore, D., & Sorrentino, L. (2019). Seismic demand of the 2016–2017 Central Italy earthquakes. Bulletin of earthquake engineering, 17(10), 5399-5427.

McCorry, L. K. (2007). Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 71(4).

Myers, D., & Wee, D. F. (2005). Disaster mental health services. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 7(3), 261.

Nuttman-Shwartz, O. (2019). Behavioral responses in youth exposed to natural disasters and political conflict. Current psychiatry reports, 21(6), 1-9.

Öhman, A. (2005). The role of the amygdala in human fear: automatic detection of threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(10), 953-958.

Reynolds, M. W., Nabors, L., & Quinlan, A. (2000). The effectiveness of art therapy: does it work?. Art Therapy, 17(3), 207-213.

Ross III, D. B., & Coambs, E. (2018). The impact of psychological trauma on finance: Narrative financial therapy considerations in exploring complex trauma and impaired financial decision making. Journal of Financial Therapy.

Sneath, J. Z., Lacey, R., & Kennett-Hensel, P. A. (2009). Coping with a natural disaster: Losses, emotions, and impulsive and compulsive buying. Marketing letters, 20(1), 45-60.

Steimer, T. (2002). The biology of fear-and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialoagues in Clinical Neuroscience, 4 (3), 231-249.

Stephens, A. N., & Groeger, J. A. (2011). Anger-congruent behaviour transfers across driving situations. Cognition & emotion, 25(8), 1423-1438. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.551184

Templeton, A., Guven, S. T., Hoerst, C., Vestergren, S., Davidson, L., Ballentyne, S., ... & Choudhury, S. (2020). Inequalities and identity processes in crises: Recommendations for facilitating safe response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3), 674-685.

Vandervoort, D. J. (2001). Cross-cultural differences in coping with sadness. Current Psychology, 20(2), 147-153.

Vázquez, C., Cervellón, P., Pérez-Sales, P., Vidales, D., & Gaborit, M. (2005). Positive emotions in earthquake survivors in El Salvador (2001). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19(3), 313-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.03.002

Vestergren, S., Sefa Uysal, M., & Tekin, S. (2022). Do disasters trigger protests? A conceptual view of the connection between disasters, injustice, and protests–the case of COVID-19. Frontiers in Political Science.

World Meteorological Association. (2021, August 31). Weather-related disasters increase over the past 50 years, causing more damage but fewer deaths. [Press release]. https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/weather-related-disasters-increase-over-past-50-years-causing-more-damage-fewer

External links

[edit | edit source]

World Meterological Association press release on increasing natural disasters