Motivation and emotion/Book/2021/Psychopathy and violence

What is the relationship between psychopathy and violent behaviour?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

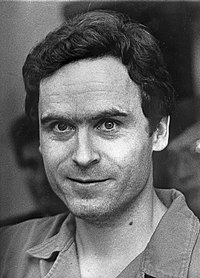

When thinking of psychopathy, most people tend to think of serial killers and violent, manipulative offenders. Ted Bundy is a prime example of a psychopathic serial killer. He is known for the violent murders and acts of necrophilia on approximately 30 women. Bundy was charismatic, intelligent, highly manipulative and deceitful, which aided his ability to escape legal grasps for many years (Ramsland, 2013). It is evident that psychopathic tendencies are commonplace among serial killers and violent offenders, as depicted by numerous famous killers in history (e.g. Ed Gein, Albert DeSalvo, and Jeffrey Dahmer). However, not all psychopaths are violent. So what is the relationship between aggression and psychopathy?

Many researchers have attempted to understand psychopathy and its origins over the years but there is yet to be a unified understanding of the construct (Brzovic et al., 2017). Understanding the association of psychopathic personality traits and aggression is imperative for predicting future violent behaviour and understanding the source of violence exhibited by these individuals. Theories from the cognitive model, biological model, and environmental influences assist with understanding psychopathy. As will research relating to the motivations behind aggressive behaviour in psychopathic individuals.

Focus questions:

|

Understanding psychopathy

[edit | edit source]Psychopathy is largely characterised by a lack of empathy and remorse, callousness, and impulsivity (Miller & Lynam, 2015; Marcus et al., 2011). Psychopathy is not listed as a mental disorder under the DSM-5; it is primarily viewed as a personality construct or disorder defined by a number of personality traits (Miller & Lynam, 2015). Hare (2003) developed a checklist to identify individuals with psychopathy and psychopathic traits. It is referred to as the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) and it recognises 20 personality traits and constructs that define psychopathy. The PCL-R allows researchers and clinicians to measure and identify individuals with psychopathic tendencies using self-report methods. These traits can be divided into four major components, namely superficial charm, pathological lying, manipulation, and grandiosity (Miller & Lynam, 2015). There are multiple theories that explain the aetiology of psychopathy and how it can be understood.

Cognitive perspective of psychopathy

[edit | edit source]Cognitive theorists consider psychopathy a developmental disorder, resulting from cognitive dysfunction. There are two major sources of dysfunction, which are attentional and emotional processing (Blair, 2013). The response modulation hypothesis suggests that psychopathic individuals have issues with attention towards secondary information and non-dominant cues, including emotional cues (Blair, 2013; Anderson & Kiehl, 2015). Meaning it is more difficult for individuals with psychopathy to pay attention to information that is not central to goal-directed behaviour. Secondly, deficits in emotional processing have been found. Individuals with psychopathy present with decreased ability to recognise emotional expressions, specifically sadness, happiness, and fear, however, they can recognise expressions of anger and disgust. Moreover, they have impaired automatic responses to other people's pain and suffering (Blair, 2013).

|

Case study

Derek is focused on getting to the coffee shop before it closes. He sees a woman in front of him blocking the path. She is in pain, this is evident by the expression on her face. Derek snaps at her to get out of the way, he does not realise she is distressed and is determined to make it to the coffee shop. Unlike most people, Derek does not react to the distress of others. Most people would feel empathy and assist the woman in pain, however Derek is purely focused on obtaining his goal and cannot process the secondary stimuli around him, such as emotional expressions. |

Neurobiological theories of psychopathy

[edit | edit source]

Neurobiological theories of psychopathy suggest that psychopathic individuals have abnormalities in the structure of the brain. Specifically, areas that involve higher-order processing of emotions. These include the limbic and paralimbic networks of the brain. Blair's neurobiological model argues that the amygdala is dysfunctional, leading to deficits in forming associations between environmental cues and emotional states (Anderson & Kiehl, 2015). Blair (2010) found that individuals with psychopathic tendencies show impaired functioning on tasks utilising the amygdala, such as fearful face recognition, passive avoidance learning, and aversive conditioning. Further, abnormalities in other areas of the brain have also been implicated in explaining psychopathy. These include the prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, insula, cingulate cortex, and anterior temporal cortex. For example, damage to the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate has been linked to deficits with cognitive control, disinhibition, and hostility (Anderson & Kiehl, 2015).

Environmental influences

[edit | edit source]Psychosocial factors such as abuse, particularly from caregivers, and growing up in foster care have been associated with higher rates of psychopathic traits (Campbell et al., 2004). Parenting practices have also been linked with development of psychopathic traits. Children who were subjected to harsh and negative parenting were more likely to display antisocial behaviour, callous-unemotional traits, manipulation, and erratic lifestyle as adults (Dotterer et al., 2021).

Do certain psychopathic traits lead to aggression?

[edit | edit source]Psychopathy is one of the greatest risk factors for violent behaviour (Thomson et al., 2019). So what is it about this notorious personality construct that leads to violent and aggressive behaviour? Extensive research has strived to understand this question. Psychopathy is characterised by a range of personality traits, from manipulation and lack of remorse to erratic and antisocial behaviour. Research suggests that specific psychopathic personality traits correspond with different subtypes of aggression.

Instrumental vs reactive aggression

[edit | edit source]Instrumental aggression is goal-driven. The individual is motivated to reach a certain outcome, in other words, there is a purpose behind the aggressive behaviour. In comparison, reactive aggression is viewed as an emotional response driven by anger, impulsion, and defensiveness in response to a threat. Evidence suggests psychopathy is significantly associated with both instrumental and reactive aggression (Miller & Lynam, 2003; Reidy et al., 2007). It has further been proposed that different traits and factors of psychopathy manifest differently in different types of aggression (Reidy et al., 2007). Affective aspects of psychopathy, such as pathological lying, grandiosity, lack of empathy and remorse, has been associated with a higher risk of both types of aggression. Antagonism was significantly linked with this factor of psychopathy, and predicted all types of aggressive behaviour. Contrastingly, socially deviant aspects of psychopathy, such as impulsivity, juvenile delinquency, and early behavioural problems, have been associated with reactive aggression. This antisocial factor of psychopathy is high in neuroticism and thereby aggression is triggered by provocation (Reidy et al., 2007).

Other types of aggression

[edit | edit source]Another type of aggression associated with psychopathic tendencies is relational aggression. Relational aggression refers to non-physical aggressive behaviour that harms an individual's feelings of acceptance and group inclusion, and damages relationships. Relational aggression can be direct or indirect. Direct relational aggression includes threats to end a relationship or social exclusion when the individual does not get what they want and the victim does not conform with demands. Conversely, indirect aggression refers to manipulative, bullying behaviours. These can include covert manipulation tactics, spreading rumours and gossiping (Czar et al., 2010). It is worth noting, this type of aggression can be common in the corporate workplace. Research suggests that supervisors and directors with psychopathy are associated with increased aggressive behaviour in the workplace (Smith & Lilienfield, 2013).

A study conducted by Czar and colleagues explored the relationship between relational aggression and psychopathic personality traits. They also examined differences between males and females. They found that individuals with psychopathic tendencies were at higher risk of demonstrating relational aggression. When comparing males and females with psychopathic traits they found both demonstrated a higher likelihood to engage in this form of aggression. Socially deviant components of psychopathy were associated with relational aggression and, unlike previous research, they also found affective factors of psychopathy were associated (Czar et al., 2010). Further, it has been theorised that the relationship between psychopathy and relational aggression can be explained by physiological cortisol levels. Whereby, higher levels of cortisol correlate with antisocial factors of psychopathy, and lower levels of cortisol are linked to callous and cold-hearted factors of psychopathy (Vaillancourt & Sunderani, 2011).

The dark triad and aggression

[edit | edit source]

The dark triad refers to a group of personality constructs that are considered malevolent and socially-averse (Muris et al., 2017; Pailing et al., 2014). These include psychopathy, machiavellianism, and narcissism. Psychopathy is characterised by low empathy and callousness, whereas machiavellianism is associated with selfishness and manipulation, and narcissism is characterised by grandiosity and self-affirmation (Pailing et al., 2014). Studies have examined the relationship between the dark triad and aggression and found associations with violence. However, the association is primarily with psychopathy, rather than narcissism and machiavellianism. When measured for aggressive tendencies, psychopathy was the only personality construct to positively correlate with physical aggression. Although, machiavellianism was associated with hostility, whereas narcissism negatively correlated with both (Jones & Neria, 2015). Further, a study conducted by Pailing and colleagues found that psychopathy was the only personality trait that significantly predicted violent behaviour. Moreover, they noted that psychopathy was the "darkest" personality construct within the dark triad, with machiavellianism coming in second (Pailing et al., 2014).

Specific psychopathic traits can predict violent or aggressive behaviour. Findings from Jones and Neria's study, which examined the relationship between aggression and dark triad personalities, supported this statement. They suggested that the psychopathic trait of manipulation was not associated with aggression but erratic, antisocial, and callous behaviours were (Jones & Neria, 2015).

Emotional regulation and psychopathy

[edit | edit source]Emotional regulation refers to the ability to effectively manage emotions. Without this mechanism, people would be unable to cope with emotional experiences and strenuous situations in daily life (Rolston & Lloyd-Richardson, 2017). An early theory of psychopathy proposed by Cleckley, referred to an inclusion of psychopathy criteria as an "absence of nervousness or psychoneurotic manifestations". This account of psychopathy emphasises the absence of emotion (Garofalo et al., 2020).

Emotional dysregulation

[edit | edit source]It is clear that individuals with psychopathy display deficits in emotional functioning, such as lacking empathy and guilt. Research exploring the relationship between emotional regulation and psychopathy has been fruitful (John & Eng, 2014; Garofalo et al., 2020). A study conducted by Garofalo and colleagues measured self-reported emotional regulation and psychopathic traits among community and offender samples to determine the extent of the relationship, and whether some psychopathic components were more significantly associated. The findings indicated a strong association between psychopathic personality traits and emotional dysregulation. Moreover, there was no difference between psychopathy factors and emotional regulation, meaning poor emotional regulation levels were consistent across affective and antisocial factors of psychopathy. These findings suggest that emotional dysregulation plays a significant role in understanding psychopathy and the maladaptive functioning of individuals with psychopathic tendencies (Garofalo et al., 2020).

Explaining the psychopathy-aggression relationship

[edit | edit source]Evidently, emotional regulation is associated with psychopathy. In addition, emotional regulation has been linked with aggressive behaviour, and it is clear that psychopathy is also associated with aggression. It has been suggested that that psychopathy indirectly affects aggression through emotional dysregulation (Garofalo et al., 2020). Garofalo and colleagues found emotional dysregulation mediated part of the relationship between aggression and psychopathic traits. Further, these indirect effects accounted for all types of aggression and psychopathic traits. However, some associations were stronger than others, for example, the indirect effect on reactive aggression was significantly higher than proactive aggression (also referred to as instrumental aggression). This demonstrates that emotional regulation plays an important role in the explanation of psychopathy-related aggression, however, it does not fully account for it. The important application of these findings is the implications for treating and preventing aggression and violent behaviour in offending psychopathic individuals (Garofalo et al., 2020).

It has been indicated emotional regulation plays a role in impulsive aggression, which is commonly exhibited by individuals with psychopathy. Ireland and colleagues noted an association between the sensitivity to emotion aspect of poor emotional regulation and aggression. Moreover, they found a link between emotional detachment, which includes callousness, unemotional, and uncaring properties, psychopathy and instrumental aggression. These findings suggest instrumental aggression associated with psychopathy is influenced by emotional dysregulation. Notably, emotion regulation associated with emotional detachment significantly explains the psychopathy-aggression relationship (Ireland et al., 2019).

|

Case study

Monty has completed a psychopathy test before and has noticed he scores highly, particularly on impulsivity and erratic behaviour. If someone or something frustrates him he immediately reacts aggressively. For example, one day Monty was driving to work and someone cut him off. This angered him and impulsively he started beeping his horn and trying to run the other vehicle off the road. Monty is displaying poor emotional regulation and reactive aggression, it is possible these are associated with psychopathic tendencies. |

Measuring and predicting violent behaviour

[edit | edit source]The ability to measure psychopathy is essential for understanding and researching the disorder. A common tool for measuring psychopathy is the use of checklists and inventories, also referred to as 'tests'. As briefly discussed at the beginning of the chapter, the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised is a well-known test used to determine psychopathy levels in clinical and research settings. It is comprised of 20 sections to measure traits and behavioural components associated with psychopathy. The items are scored out of three and can be divided into two factors of psychopathy. These consist of affective and interpersonal components of psychopathy (Factor 1), and antisocial and criminal behaviour aspects of psychopathy (Factor 2) (Smith & Lilienfield, 2013). The Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised (PPI-R) also assesses psychopathy, focusing on personality factors and excluding antisocial behaviour aspects. Aligning with the PCL-R, the PPI-R also supports a two-factor approach. The two factors are Fearless Dominance, consisting of fearlessness, social potency, and stress immunity; and Self-Centred Impulsivity, which consists of impulsive nonconformity, Machiavellian egocentrism, carefree nonplanfulness, and blame externalisation. There is a final item, coldheartedness, which does not fit under either factor (Marcus et al., 2013).

The usefulness in these scales for understanding and researching psychopathy is imperative for predicting future violent behaviour. Both scales have been found to significantly predict violence (Camp et al., 2013). A study conducted by Camp and colleagues compared the PCL-R and PPI to examine the prediction of violence, focusing on the two factors of psychopathy and motivation for violence. The study measured psychopathic traits on both scales from a sample of prison inmates and followed up three months later to determine if the participants had engaged in violent behaviour. The PPI strongly predicted immediate and future violence, with the majority of participants motivated by reactive aggression. Impulsive and antisocial behaviour were associated with violence motivated by instrumental reasons, and predictive of long-term patterns of violent behaviour (Camp et al., 2013). Measuring psychopathic traits and motivations for violence is crucial in predicting violence and implementing intervention and prevention strategies.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]This chapter dissected the relationship between psychopathy and aggression. Psychopathy is a complex construct that has been widely researched, and there is undoubtedly an association between aggressive behaviour and psychopathic tendencies. Theories suggest that psychopathy stems from a level of dysfunction and impairment in structures of the brain and cognition. Some of these impairments indicate deficits in emotional processing. Emotional regulation is negatively correlated with psychopathic traits, and poor emotional regulation has been associated with some types of aggression. Psychopathic traits have consistently been associated with aggression, including instrumental, reactive, and relational aggression. Specifically, psychopathy has been linked with aggression through emotional dysregulation. Additionally, affective components of psychopathy have been associated with all three types of aggression, whereas the antisocial aspects of psychopathy have been primarily associated with reactive and relational types of aggression. Understanding the relationship between psychopathy traits, aggression, and emotional regulation is significant for future preventative measures to reduce aggressive behaviours in offenders. Further, measuring psychopathic traits is fundamental for understanding and researching psychopathy, including predicting violence. Predicting violent behaviour is crucial for implementing intervention and prevention strategies for individuals with psychopathic tendencies.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Dark Triad Personality and Emotion (Book chapter, 2021)*Psychopathy (Book chapter, 2010)

- Psychopathy and emotion (Book chapter, 2015)

References

[edit | edit source]Blair, R.J.R. (2010), Psychopathy, frustration, and reactive aggression: The role of ventromedial prefrontal cortex. British Journal of Psychology, 101, 383-399. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609X418480

Blair, R. J. R. (2013). Psychopathy: cognitive and neural dysfunction. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 15(2), 181. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.2/rblair

Brzović, Z., Jurjako, M., & Šustar, P. (2017). The kindness of psychopaths. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 31(2), 189-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698595.2018.1424761

Camp, J. P., Skeem, J. L., Barchard, K., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Poythress, N. G. (2013). Psychopathic predators? Getting specific about the relation between psychopathy and violence. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 81(3), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031349

Czar, K. A., Dahlen, E. R., Bullock, E. E., & Nicholson, B. C. (2011). Psychopathic personality traits in relational aggression among young adults. Aggressive behavior, 37(2), 207-214. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20381

Dotterer, H., Vazquez, A., Hyde, L., Neumann, C., Santtila, P., Pezzoli, P., . . . Burt, S. (2021). Elucidating the role of negative parenting in the genetic v. environmental influences on adult psychopathic traits. Psychological Medicine, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0033291721002269

Garofalo, C., Neumann, C. S., Kosson, D. S., & Velotti, P. (2020). Psychopathy and emotion dysregulation: More than meets the eye. Psychiatry Research, 290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113160

Garofalo, C., Neumann, C. S., & Velotti, P. (2020). Psychopathy and Aggression: The Role of Emotion Dysregulation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519900946

Hare, R. D. (2003). The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (2nd edn). Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.

Ireland, J. L., Lewis, M., Ireland, C. A., Derefaka, G., Taylor, L., McBoyle, J., Smillie, L., Chu, S., & Archer, J. (2020). Self-reported psychopathy and aggression motivation: a role for emotions? The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 31(1), 156-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2019.1705376

John, O. P., & Eng, J. (2014). Three approaches to individual differences in affect regulation: Conceptualizations, measures, and findings. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 321–345). The Guilford Press.

Jones, D. N., & Neria, A. L. (2015). The Dark Triad and dispositional aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 360-364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.018

Marcus, D. K., Fulton, J. J., & Edens, J. F. (2013). The two-factor model of psychopathic personality: Evidence from the Psychopathic Personality Inventory. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 4(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025282

Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2003). Psychopathy and the five-factor model of personality: A replication and extension. Journal of personality assessment, 81(2), 168-178. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8102_08

Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2015). Understanding psychopathy using the basic elements of personality. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(5), 223-237. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12170

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., & Meijer, E. (2017). The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the dark triad (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616666070

Pailing, A., Boon, J., & Egan, V. (2014). Personality, the Dark Triad and violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.018

Ramsland, K. (2013). THE MANY SIDES OF TED BUNDY. Forensic Examiner, 22(3), 18-25. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/1439533531?fromopenview=true&pq-origsite=gscholar

Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., Miller, J. D., & Martinez, A. M. (2007). Psychopathy and aggression: Examining the role of psychopathy factors in predicting laboratory aggression under hostile and instrumental conditions. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.001

Rolston, A., & Lloyd-Richardson, E. (2017). What is emotion regulation and how do we do it. Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery, 1-5.

Smith, S. F., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2013). Psychopathy in the workplace: The knowns and unknowns. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(2), 204-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.007

Thomson, N. D., Kiehl, K. A., & Bjork, J. M. (2019). Violence and aggression in young women: The importance of psychopathy and neurobiological function. Physiology & behavior, 201, 130-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.11.043

Vaillancourt, T., & Sunderani, S. (2011). Psychopathy and indirect aggression: The roles of cortisol, sex, and type of psychopathy. Brain and Cognition, 77(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2011.06.009

External links

[edit | edit source]- Exploring the mind of a psychopathic killer (TED Talk)