Motivation and emotion/Book/2021/Criminal culpability and motivation

How does motive impact on criminal culpability?

Overview

[edit | edit source]| “ | No man can be judged a criminal until he is found guilty; nor can society take from him the public protection until it has been proved that he has violated the conditions on which it was granted. What right, then, but that of power, can authorize the punishment of a citizen so long as there remains any doubt of his guilt? | ” |

| — Beccaria, 1819 - On crime and punishment | ||

Motivation refers to an individual’s internal drive or effort to engage in a particular behaviour persistently. In a criminal context, motive refers to an individual's reason/s for committing a crime. There are numerous motives for an individual to engage in criminal behaviour but there are a few which have been consistently used to explain why people commit crime: power, greed, jealousy, hatred, anger, revenge and sexual desire.

Once a crime has been committed and a suspect has been arrested, the defendant is taken into custody where they are put on trial in court (see Figure 1.). During these criminal proceedings, the prosecutor has the task of establishing the burden of proof or culpability and the defendant's lawyer or defence has the task of creating doubt in the prosecutions case.

Are there psychological theories to explain criminal behaviour, and what motivates an individual to engage in this behaviour? Also what is criminal culpability and are there certain attributes and behaviours which make an individual more or less culpable? This chapter answers these questions and addresses whether criminal culpability is affected by motive.

Focus questions:

|

What are the main psychological theories of criminal behaviour?

[edit | edit source]There are many different perspectives which endeavour to define why people commit crime. Those who practice and research in psychology have theorised possible causes for criminal behaviour. Below are some of the main theories attempting to explain the reasoning for and causes of criminal behaviour.

General theory of crime

[edit | edit source]Michael Gottfredson and Travis Hirschi were notable American criminologists focused on self-control and its influence on criminal behaviour and together were responsible for the development of the General Theory of Crime (Bernard, 2021c). The authors were interested in the explanation of crime and sought to discover a relationship between an individual's level of self-control and crime (Wikert 2019a). According to Gottfredson and Hirschi, low self-control is a trait which is acquired during childhood as a result of inadequate socialisation. This low self-control presents as recklessness and risky behaviour, with an individual embodying narcissistic and volatile characteristics (as cited by Lianos & McGrath, 2017). The likelihood that an individual will participate in criminal and antisocial behaviour is greater when they have low self-control. The basis for this concept that individuals with low self-control are lacking the ability to regulate their actions when pursuing something they desire (Gottfredson & Hirschi as cited by Lianos & McGrath, 2017). There are some that contend that low self-control cannot be defined as the cause of all types of crime due to lack of observed evidence (Wilkert, 2019a). Furthermore, Akers and Sellers emphasise that low self-control is the only underlying cause of criminal behaviour (as cited by Wilkert, 2019a). Additionally, Bensen and Moore found that Gottfredson and Hirschi's theory could not be used to explain white-collar crime (DeLisi & Vaughn, 2008).

Strain theories

[edit | edit source]Robert Merton was considered to be one of the most influential sociologists in America of the 20th Century. His research focused on the motivations (both rewards and punishments) that contribute to behaviour (Kaufman, 2003). He also played a significant role within the criminology discipline by developing the strain theory. Merton describes that a strain is the lack of cultural, social or ethical standards that prevent an individual from suceeding in society. As a result of this strain, the individual is often compelled to engage in criminal behaviour (Ozbay et al. 2006).

. Although there is much support for this theory, it is not without its criticisms. According to Bernard, empirical testing of this theory was unable to find a significant correlation between strain and delinquency (1984; Farnworth & Leiber, 1989). Similarly, Rebellon et al., assert individuals experiencing stressful life events may turn to crime as an outlet, but these events were not found to be correlated the standards mentioned by Merton (2009). Additionally, Agnew argues that the range of strains were limited (2001).Furthermore, Agnew posits this theory has insufficient categories for a wide range of strains to be explained or measured (2001). This wide scope impedes the ability for researchers to refute (Agnew, 2001).

Robert Agnew is a sociology professor at Emory University but is more well-known for his work in the criminology field, focusing on the explanation of why crime occurs and its causes. His research led to the innovation of General Strain Theory (GST; Hunt, 2016). Agnew asserts GST is exhibited when individual's experience additional strains or stressors in their lives, which can create a negative emotional state (2001).These negative emotions often causes their behaviour to be reactive and corrective, often displayed in the form of crime (Grobbink et al., 2015).

Aileen Wuornos (see Figure 2) is a good example of Agnew's GST. In her childhood, Wuornos experienced multiple traumatic events or strains which accumulated, leading to the murders she committed in her later life. According to Arrigo and Griffin, at a young age, Wuornos and her brother were abandoned by their mother to live with their grandparents and while her father was imprisoned, he committed suicide (2004). Whilst living with her grandparents, Wuornos had been physically and emotionally abused by her grandfather. Additionally she was kicked out of her grandparents home when she was a teenager due to pregnancy and was forced into a transient lifestyle (Arrigo & Griffin, 2004). It is difficult to determine which strain provoked Wuornos to react in such an extreme way, though it can be said that the accumulation of this strain can be correlated to this.

Differential association & social learning theory

[edit | edit source]Edwin Sutherland was a prominent criminologist whose work was said to be significantly influential to the field of criminology during the 20th Century (Friedrichs, 2016; Bernard, 2021). Sutherland was renowned for his development of differential association theory of crime (Bernard, 2021a). According to Moon et al (2011) differential association (DA) asserts that criminal behaviour, like lawful behaviour, can be learnt. If an individual’s associates (i.e., friends and family) engage in behaviours considered to be deviant or antisocial, the individual is more likely to also participate in those behaviours. It should be noted, behaviour is dependent on the frequency, duration, priority and intensity of an individual's associations (Moon et al, 2011).

A classic example of Sutherland's DA is the infamous couple, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Champion Barrow (see Figure 3). In 1934, Bonnie and Clyde were wanted for a string of robberies, suspected murders and a kidnapping. Although, before an arrest could be made, the couple were ambushed and shot to death by police officers (FBI, n.d.) Although it is impossible to distinguish whether Bonnie and Clyde would have encountered the same fatal end if they had not met, it is clear that the association of these individuals played a significant role in their learnt criminal behaviour.

Although DA has been well received by the criminology and psychology disciplines, there are still those that challenge this theory (Vinney 2021; Lokanan; 2018). According to Vinney, the concept of individual differences is one area that DA fails to explain (2021). Every individual is unique, and with that uniqueness comes a different motivation behind their behaviour (Vinney, 2021). Due to this inability to explain these differences, DA is therefore unable to be applied to group differences in criminal behaviour (Lokanan, 2018).

Similarly, Akers social learning theory (SLT), which is based on Sutherland's DA, implies there are significant learning principles that determine individual differences in criminal behaviour (Morris & Higgins, 2010). Ronald Akers was a sociologist and criminologist whose key interest was determining whether learning was responsible for criminal behaviour (Bernard, 2021b). According to SLT, individuals employ the values, attitudes, and behaviours learnt through vicarious experience from those they associate with, whether it be prosocial or antisocial. Therefore, these individuals are more likely to participate in deviance and criminal behaviour whether they have peers who also employ these values, attitudes and behaviour (Moon et al., 2011).

Despite the significance of Akers SLT, recent critiques have identified areas where this theory is unable to explain certain aspects of criminal behaviours. Firstly, there has been debate regarding empirical support for this theory. According to Proctor and Neimeyer, limited empirical testing has been performed on the key fundamental principles of SLT, (i.e., operant conditioning and vicarious reinforcement; 2020). Further, when empirically tested, these principles produced insignificant results (Proctor & Neimeyer, 2020).

What motives do individuals have for engaging in criminal?

[edit | edit source]Generally, motive or motivation for one's behaviour is the internal drive to attain an object or position of desire (Reeve, 2018, p. 8). In a criminal context, motive is what causes the individual to commit a criminal offence. It is said that what a person wants and/or needs will establish what their motive is for their criminal behaviour (Australian Law Commission, 2014). The range of motives for criminally inclined individuals is seemingly endless but there are several motives that are often considered for crime.

Power and greed

[edit | edit source]Power is an individual's ability to influence the thoughts, feelings and actions of others. An individual's need for power can be explained using McClelland's trichotomy of needs. According to McClelland's theory, an individual’s level of motivation is based on one of three needs: need for achievement, need for affiliation and need for power (as cited by Harrell & Stahl, 1981).When an individual is motivated by a need for achievement, they constantly require the acknowledgement and recognition for the things that they do, with a main focus on fulfilling the task at hand. Those motivated by a need for affiliation require meaningful and harmonious relationships with others. Individuals motivated by affiliation are motivated to the development and maintenance of social connections. Individuals motivated by a need for power are compelled to seek positions in which they can influence, control or have authority over others (Dehgan Nayeri & Jarafour, 2015).

Greed is often referred to as a seemingly limitless desire for tangible (i.e., money) or intangible (i.e., power) things than what is needed (Seuntjens et al 2014). When considering needs, Maslow's hierarchy of needs provides a basis for understanding greed. According to Maslow's hierarchy of needs (see figure 4), individuals require certain needs to acheive optimum development. These needs fall into one of five categories: physiological, safety and love/belonging which are deficiency needs (low order) and esteem and self-actualisation which are growth needs (high order; Noltemeyer et al., 2021).

Physiological needs are those that are required for biological functioning (food, water, shelter, etc.), and safety needs are those essential for maintaining security (employment, family etc.). Love/belonging needs are those necessary for developing and sustaining relationships. Esteem needs are those involved with self-worth and accomplishment, esteem needs are divided into two groups: self-esteem and status among peers. Finally, self-actualisation needs refer to the realisation of one's potential (McCleod, 2020). Maslow proposed that until the deficiency needs are maintained adequately, an individual is unable to advance to realising their growth needs (as cited by Noltemeyer et al., 2021).

|

In 2008,Bernie Madoff was arrested for what is still considered one of the largest Ponzi schemes in American history. Over 20 years, Madoff succeeded in deceiving thousands of victims into investing in his company, where he obtained over $20 billion (Ortner, 2019). So, what happened in Madoff’s life which led him down this path? Whilst in prison, Madoff revealed that he had watched his father lose everything after his sporting goods store went bankrupt. This prompted him to swear to do ‘whatever it took’ to succeed in his career (Hayes, 2021). Although, it is unclear what was going through Madoff's mind, one can speculate that seeing his father broke, significantly impacted psychological well-being and motivated him to commit fraud. You can read more about Bernie Madoff's crimes via: A Case Study of a Con Man: Bernie Madoff and the Timeless Lessons of History's Biggest Ponzi Scheme |

Jealousy

[edit | edit source]Jealousy occurs when an individual feels or expresses resentment towards someone and perceived success, possessions or position. According to Rydell and Bringle, jealousy can be divided into two types: reactive and suspicious. Reactive jealousy refers to the actual indiscretions which can occur in a relationship which severs the bond whereas suspicious jealousy occurs in response to cues of jealousy without the presence of actual events to provoke jealousy (2007).

The dynamic functional model of jealousy (DFMJ) has been used to describe mechanisms of jealousy. According to Chung and Harris, DFMJ takes a Darwinian approach to emphasise that negative emotions were developed out of the necessity from threats faced by an individual’s ancestors (2018). Furthermore, independently, emotions are used to motivate behaviour in response to a threat (Chung & Harris, 2018). In this regard, jealousy can be explained with the same approach. When an individual appraises a person as a threat to their relationship, the feeling of jealousy arises. This emotion can be displayed in one of two ways, fixating on the relationship or fixating on the object of their jealousy (Chung & Harris, 2018). Additionally, jealousy is said to motivate an individual to insert themselves between their loved one and rival as a way of preventing them interacting, in hopes of restoring the relationship with the loved one (Chung & Harris, 2018).

Hatred

[edit | edit source]Hatred occurs when an individual extremely dislikes something or someone. According to Opotow and McClelland, the emergence of hate in an individual stems from precursory experiences, situational factors and illogical attitudes or beliefs. This forms an individual’s inclination to be hateful and is a consequence of negative affect, accessibility to social groups and moral justifications (2007). The intensification of hating has been used to describe the phenomenon of hate. Opotow and McClelland affirm that there are five components to this theory: antecedents, affect, cognitions, morals, and behaviours (2007).

Another significant theory used to explain hate is the duplex theory of hate. According to Sternberg, hate can be explained by two in-sync components. The first being the triangle of hate which contain three parts: negation of intimacy, passion, and commitment. The second component is comprised of a series of narratives personifying the object of hate which produce opposing triangles of hate (2018). The most infamous hate crime is the September 11 attacks in New York, USA (see figure 6)

Anger

[edit | edit source]An individual experiences anger in response to a comment, person or situation which is insensitive, provocative or threatening in nature. A person's anger can fluctuate from slight agitation to blind rage. Anger is a common motive for individuals to engage in criminal behaviour. There is a notable typical theory of anger: t the general aggression model (GAM; Anderson & Bushman, 2018). According to Anderson and Bushman, GAM consists of two components: personality development and social encounters, which are applied to anger and aggressive behaviour. These components demonstrate the differences between risk factors and processes that are stable and long-term and those that are temporary and short-term (2018). Anderson and Bushman also concede that there are potential mediating factors: internal states, which are the thoughts, feelings, and the physiological arousal related to anger and appraisal and decision making processes, which are automatic and controlled.

Revenge

[edit | edit source]Revenge is when an individual causes pain or harm to another person as retribution for a real or perceived harm done to them. Grobbink et al., stated that feelings such as hostility and hatred are often associated with revenge (2014). Bies et al., suggest that after individuals experience a traumatic event (real or imagined), there is a tendency to ruminate about it and blame the person responsible. Depending on the appraisal of the situation, will determine the likelihood of the individual becoming angry, and fantasising or behaving in a vengeful manner (as cited by Grobbink et al., 2014). Furthermore, attribution theory assert that individuals attribute blame either internally or externally for negative situations they experience. Therefore, an individual will often direct their vengeful or aggressive urges inwardly or outwardly (Grobbink et al., 2014). A good example of an outward display of vengeful behaviour when an individual murders another due to adultery with the individual's wife.

|

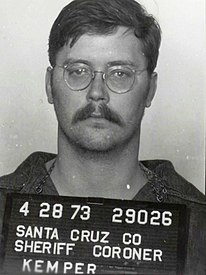

Edmund Kemper was famously known as the 'co-ed' killer', a nickname he obtained through his murders of six young females. However, these were not Kemper's first crimes, in fact, he murdered his grandparents at the age of fifteen just to 'see what it felt like' (Greig, 2010). After serving 5 years at Atascadero State Hospital (maximum-security detention for those deemed psychologically unfit), Kemper was released into his mother's care. Doctor's were against this living arrangement due to the psychological and emotional abuse Kemper had suffered at the hands of his mother (Innes, 2004). This fact makes it easy for one to assume that he killed women, including his mother, out of a need for revenge. You can read more about Edmund Kemper's murders via: Edmund Kemper Biography |

Sexual desire

[edit | edit source]Sexual desire is an individual's appetite for activities or objects of a sexual nature. When discussing sexual desire as motive for crime, there are two notable theories: the incentive model of sexual motivation and the integrated theory of sexual offending (ITSO; Smid et al., 2019; Ward & Beech, 2006). According to Smid et al., sexual motivation comprises of liking, wanting, and (dis)inhibition processes, to demonstrate sexual behaviour (2019). The incentive model of sexual motivation asserts that engaging in sexual interaction and reaching gratification allows the motivational cycle of liking, wanting, and disinhibition to be recurring. Furthermore, the cycle is described as:

| “ | A competent sexual stimulus (in vivo or fantasy) triggers a liking and wanting reaction that, if not inhibited, leads to action/approach in search of a stronger sexual stimulus. Experience (in vivo or fantasy)contributes to the incentive salience of a stimulus. The cycle repeats itself toward sexual gratification.Other emotional stimuli can increase sexual motivation through excitation transfer and may become included in the cycle (sexual deviance) | ” |

| — Smid et al., 2019 | ||

Whereas, Ward and Beech., ITSO suggests that sexual offending occurs as a result of causal variables that interact with one another (2006). ITSO comprises of three different factors: biological (i.e., genetics and brain) ecological (i.e., social and cultural) and neuropsychological (Ward & Beech., 2006).

|

Theodore Bundy is thought to be one of the most notorious and disturbing serial killers in American history. Though, the number of women that were murdered by Bundy, authorities believe that the numbers reached over forty women (Jenkins, 2021). Bundy's crimes were particularly sexually sadistic and, at times necrophiliac, so it is easy to understand how he was profiled as sexually motivated (Williams, 2018). Bundy's childhood could have also played a role in his crimes (Greig, 2010). Bundy was raised to believe that his mother was his sister, where his grandfather (her father) brutally abused them (Serena, 2021). You can read more about Ted Bundy's murders via: Ted Bundy Biography |

What is criminal culpability and what factors increase/decrease culpability?

[edit | edit source]When an individual is legally responsible for a criminal offence, they are said to be culpable. Essentially, how accountable the person is for a crime. Culpability also brings into question the mental state of an offender of criminal behaviour.

Mitigating & aggravating factors

[edit | edit source]Mitigating factors refers to any evidence or information presented by an offenders council to the court which may result in a lesser or reduced charge. If an individual possesses one or more of these factors, it is likely to mitigate a lesser sentence:

- They have not previously been convicted of a crime,

- How good their character is - how they conduct themselves and where their morals lie,

- How likely they are to be rehabilitated into society,

- They show genuine remorse for their criminal behaviour,

- Their age - if they are young or they are elderly

- If they have a physical illness or impairment,

- If a family member/s depend on them,

- If there is evidence of social disadvantages, childhood abuse or trauma (Warner et al., 2018).

Whereas, Aggravating factors refers to any information or conditions that increase an individual's culpability for a criminal offence. If an individual possesses one or more of these factors, it is more likely the individual will be found culpable for the crime:

- If they were in position of trust or power and abused it,

- If their victim was vulnerable - age or disabled,

- If they have caused a substantial amount of harm,

- If there evidence that the crime was planned,

- If they have previously been convicted of a crime,

- If they are on bail, parole or in breach of suspended sentence/ community order (Warner et al., 2018).

Other factors

|

|

Aaron Hernandez was a NFL tight end for the New England Patriots who managed to maintain an exceptional career in professional football. This career was terminated abruptly when Hernandez was arrested and convicted for the murder of Odin Lloyd, a semi-pro footballer. Two years into his jail sentence, Hernandez was found dead in his cell from suicide (Bertram, 2021). Upon his death, Hernandez was discovered to have chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which is caused by repetitive trauma to the brain affecting judgement, decision-making and cognition (Henne & Ventresca 2019; Kilgore, 2017). So, with this knowledge, did Aaron Hernandez have criminal mind or did his brain condition cause him to commit murder? You can read more about Aaron Hernandez via: A criminal mind? A damaged brain? Narratives of criminality and culpability in the celebrated case of Aaron Hernandez |

How do motives impact the criminal culpability of an individual?

[edit | edit source]| Actus reus non facit reum nisi mens sit

"an individual cannot be culpable for a crime unless the offence (actus reus) is committed with the knowledge or intent was criminal or wrong (mens rea)" (De Caro, 2020). |

It has been said that motive plays an important role in determining the criminal culpability of an individual. When an individual decides to criminally act upon their motive, two concepts are established. Firstly, motive explains and provides understanding for the crime they have committed. Secondly, motive impacts an individual's responsibility or culpability for that crime (Brax, 2016). Additionally, Nadler and McDonnell assert that criminal culpability could influence motive in the pursuit of linking an individual's criminal behaviour with their criminal background.In contrast, motive can be applied to aid an individual in their defence, that is, avoiding criminal culpability (2012). For example, an individual could physically assault a person in self-defence of being attacked, and this motive could help in preventing or reducing a criminal conviction (see Figure 10). Similarly, Hessick emphasises that when motive is often raised in criminal trial to convince the judge and/or jury that individual is culpable for the crime (2006).

While, substantial support has been provided for the concept that culpability is influenced by motive, there critics that believe there are significant limitations. Firstly, the way in which an individual evaluates their behaviour as morally appropriate is subjective (Eldar & Laist, 2017). Secondly, an individual's motive for committing crime is often not revealed out loud with themselves let alone with others, so it often remains inside the individual's mind. This concept makes it difficult for prosecution to prove intent. Furthermore, intent is an easier construct to find a causal relationship with offending than with motive is. This is due to the fact that a motive needs to be examined more thoroughly as an offender's mental state is subjective (Naidoo, 2017). Finally, Naidoo discovered some disharmony with legality principle, which states that culpability should not be rely on the individual's morals or motives (2017).

Quiz

[edit | edit source]

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Overall, criminal behaviour can be explained by four main psychological theories: general theory of crime, strain theory, Sutherland's differential association and Aker's social learning theory. The number of motives that people use for engaging in criminal behaviour is seemingly endless, there are common ones that seem to be used frequently: power/greed, jealousy, hatred, anger, revenge and sexual desire. Case studies of Bernie Madoff, Edmund Kemper, Ted Bundy and Aaron Hernandez have been used to demonstrate some the motives presented.

Individual's who engage in criminal behaviour must also have the intent of committing crime before they can be found culpable. Mitigating factors aid a defendant in a reduced sentence after being convicted of a crime while aggravating factors increase the defendant's culpability of the crime in question. Criminal culpability can be impacted by motive but this concept does have its limitations. The reader is encouraged to make up their own mind about whether the argument that motive does impact criminal culpability.

|

Take home message: Guilty act (criminal offence) + guilty mind (motive and intent) = guilty person (culpability) |

See also

[edit | edit source]

Criminality (Book chapter, 2011)

Criminology (Wikipedia)

Forensic psychology (Wikipedia)

Sexual violence motivation (Book chapter, 2014)

Serial killing motivation: (Book chapter, 2014)

Violent crime motivation (Book chapter, 2010)

References

[edit | edit source]Anderson, C., & Bushman, B. (2018). Media violence and the general aggression model. Journal Of Social Issues, 74(2), 386-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12275

Arrigo, B., & Griffin, A. (2004). Serial murder and the case of Aileen Wuornos: attachment theory, psychopathy, and predatory aggression. Behavioral Sciences & The Law, 22(3), 375-393. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.583

Brax, D. (2016). Motives, reasons, and responsibility in hate/bias crime legislation. Criminal Justice Ethics, 35(3), 230-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/0731129x.2016.1243826

Brezina, T. (2017). General strain theory. Oxford Research Encyclopedia Of Criminology And Criminal Justice. 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.249

Chung, M., & Harris, C. (2018). Jealousy as a Specific Emotion: The Dynamic Functional Model. Emotion Review, 10(4), 272-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073918795257

De Caro, M. (2020). “Actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea”. The concept of guilt in the age of cognitive science. Neuroscience And Law, 69-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38840-9_4

Dehghan Nayeri, N., & Jafarpour, H (2015). Relationship between clinical competence and motivation needs of nurses based on the McClelland theory. Nursing Practice Today, 1(2).

DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. (2007). The Gottfredson–Hirschi critiques revisited: Reconciling self-control theory, criminal careers, and career criminals. International Journal Of Offender Therapy And Comparative Criminology, 52(5), 520-537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x07308553

Eldar, S., & Laist, E. (2017). The irrelevance of motive and the rule of law. New Criminal Law Review, 20(3), 433-464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X07308553

Farnworth, M., & Leiber, M. (1989). Strain theory revisited: Economic goals, educational means, and delinquency. American Sociological Review, 54(2), 263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095794

Friedrichs, D. (2016). Edwin H. Sutherland: An improbable criminological key thinker — for critical criminologists and for mainstream criminologists. Critical Criminology, 25(1), 55-69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-016-9320-0

Gottfredson, M., & Hirschi, T. (2016). The criminal career perspective as an explanation of crime and a guide to crime control policy. Journal Of Research In Crime And Delinquency, 53(3), 406-419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427815624041

Greig, C. (2010). Evil serial killers: In the minds of monsters (6th ed., pp. 32-129). Arcturus.

Grobbink, L., Derksen, J., & van Marle, H. (2015). Revenge: An analysis of its psychological underpinnings. International Journal Of Offender Therapy And Comparative Criminology, 59(8), 892-907. doi: 10.1177/0306624x13519963

Harrell, A., & Stahl, M. (1981). A behavioral decision theory approach for measuring McClelland's trichotomy of needs. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 66(2), 242-247. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.66.2.242

Henne, K., & Ventresca, M. (2019). A criminal mind? A damaged brain? Narratives of criminality and culpability in the celebrated case of Aaron Hernandez. Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal, 16(3), 395-413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659019879888

Hessick, C. (2006). Motive's role in criminal punishment. Southern California Law Review, 80(1), 89-150.

Innes, B. (2004). Profile of a criminal mind (pp. 62-65). Index.

Lianos, H., & McGrath, A. (2017). Can the general theory of crime and general strain theory explain cyberbullying perpetration?. Crime & Delinquency, 64(5), 674-700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128717714204

Lokanan, M. (2018). Informing the fraud triangle: Insights from differential association theory. The Journal Of Theoretical Accounting Research, 14(1), 55-98. Retrieved 11 October 2021, from.

Moon, B., Hwang, H., & McCluskey, J. (2011). Causes of school bullying: Empirical test of a general theory of crime, differential association theory, and general strain theory. Crime & Delinquency, 57(6), 849-877. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128708315740

Morris, R., & Higgins, G. (2010). Criminological theory in the digital age: The case of social learning theory and digital piracy. Journal Of Criminal Justice, 38(4), 470-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.04.016

Nadler, J., & McDonnell, M.-H. (2012). Moral Character, Motive, and the Psychology of Blame. Cornell Law Review, 97(2), 255–304. https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/14

Naidoo, K. K. (2017). Reconsidering motive's irrelevance and secondary role in criminal law. Journal of South African Law, 2017(2), 337-351.

Noltemeyer, A., James, A., Bush, K., Bergen, D., Barrios, V., & Patton, J. (2020). The relationship between deficiency needs and growth beeds: The continuing investigation of Maslow’s theory. Child & Youth Services, 42(1), 24-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935x.2020.1818558

Opotow, S., & McClelland, S. (2007). The intensification of hating: a theory. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 68-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0033-0

Ortner, S2019). Capitalism, kinship, and fraud: The case of Bernie Madoff. Social Analysis, 63(3), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2019.630301.

Özbay, Ö., & Özcan, Y. (2006). Classic strain theory and gender. International Journal Of Offender Therapy And Comparative Criminology, 50(1), 21-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x05277665

Reeve, J. (2019). Understanding motivation and emotion (7th ed., p. 8). John Wiley & Sons.

Rybnicek, R., Bergner, S., & Gutschelhofer, A. (2019). How individual needs influence motivation effects: a neuroscientific study on McClelland’s need theory. Review Of Managerial Science, 13(2), 443-482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0252-1

Rydell, R., & Bringle, R. (2007). Differentiating reactive and suspicious jealousy. Social Behavior And Personality: An International Journal, 35(8), 1099-1114. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.8.1099

Smid, W., & Wever, E. (2019). Mixed Emotions: An incentive motivational model of sexual deviance. Sexual Abuse, 31(7), 731-764. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063218775972

Schulze, C., & Bryan, V. (2017). The gendered monitoring of juvenile delinquents: a test of power-control theory using a retrospective cohort study. Youth & Society, 49(1), 72–95. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1177/0044118X14523478

Sternberg, R. (2018). FLOTSAM: A model for the development and transmission of hate. Journal Of Theoretical Social Psychology, 2(4), 97-106. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts5.25

Tripp, T., Bies, R., & Aquino, K. (2007). A Vigilante Model of Justice: Revenge, Reconciliation, Forgiveness, and Avoidance. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 10-34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0030-3

Vereshaa, R. (2021). Determination motive through the prism of the general concept of the motives of human behaviour. International Journal Of Environmental & Science Education, 11(11), 4739-4750. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1114942.pdf.

Warner, K., Spiranovic, C., Freiberg, A., Davis, J., & Bartels, L. (2018). Aggravating or mitigating?: Comparing judges’ and jurors’ views on four ambiguous sentencing factors. Journal of Judicial Administration, 28(1), 51–66. https://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1223834/Aggravating-and-Mitigating.pdf

Ward, T., & Beech, A. (2006). An integrated theory of sexual offending. Aggression And Violent Behavior, 11(1), 44-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.05.002

Williams, D. (2019). Is serial sexual homicide a compulsion, deviant leisure, or both? Revisiting the case of Ted Bundy. Leisure Sciences, 42(2), 205-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2019.1571967

Winter, D. (2000). David C. McClelland (1917–1998): Obituary. American Psychologist, 55(5), 540-541. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.540

External links

[edit | edit source]

- Love, lust, loathing or loot — what makes a killer kill?

- Crime, culpability, and the adolescent brain

- Criminal culpability: the possibility of a general theory

- Theories and causes of crime

- Culpability levels in criminal law

- Aaron Hernandez suffered from most severe CTE ever found in a person his age (Kilgore, 2017)

- Aaron Hernandez: Timeline of his football Career, murder trials and death (Bertram, 2021)

- A common law principle (Australian Law Reform Commission, 2014)

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bernard-madoff.asp Bernie Madoff (Hayes, 2021)

- Bonnie & Clyde (FBI, n.d.)

- Does Ted Bundy’s Childhood Hold The Key To His Madness? (Serena, 2021)

- Edwin Sutherland (Bernard, 2021a)

- General theory of crime (Wikert, 2019a)

- https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html Maslow's hierarchy of needs (McCleod, 2020)

- Quote (Beccaria, 1819)

- Robert Agnew (Hunt. 2016)

- Ronald L. Akers (Bernard, 2021b)

- Social learning theory (Wikert, 2019b)

- Sutherland's differential association theory (Vinney, 2021)

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ted-Bundy Ted Bundy (Jenkins, 2021)

- Travis Hirschi (Bernard, 2021c)