Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Intranasal oxytocin and emotion

What are the emotional effects of intranasal oxytocin?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Research on oxytocin has increased drastically over the past half century, due to growing evidence of its numerous functions in human social behaviour and cognition. Initially recognised for its vital role in childbirth, lactation and sex, the nonapeptide has risen through the ranks, and has even been given nicknames such as the 'love', 'cuddle' or 'miracle' hormone just to name a few. Yet, despite the cute nicknames, oxytocin has gained even more attention due to its emerging potential as a medical intervention.

While medicinal oxytocin has been utilised for decades in intravenous form for childbirth and lactation, intranasal oxytocin (IN-OT) has been gaining popularity. This chapter will discuss intranasal oxytocin, its effects on emotion, and how it can be utilised to improve our emotional processes.

|

Focus questions:

|

Oxytocin

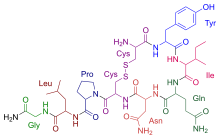

[edit | edit source]Oxytocin (OT) is a peptide hormone and a neuropeptide that plays a key role in reproductive and sexual behaviours, prosocial behaviour, social bonding, and interpersonal interactions. Manufactured in the hypothalamus, oxytocin is released by the posterior pituitary gland and released both in the brain and into the bloodstream (see Figure 1). (Kalat, 2018) It has widely been recognised for its role in childbirth and lactation, being released by the hypothalamus to induce uterine contractions to begin childbirth labour, as well as during lactation, playing a significant role in maternal behaviours and bonding. There is also a growing body of research that has implicated OT in processes of social cognition, such as increasing trust, empathy, pair bonding and social cognition. (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2011) Such evidence has demonstrated evolutionary, physiological and psychological functions of the nonapeptide.

Functions

[edit | edit source]The numerous forms of oxytocin allow for the neuropeptide and hormone to provide different functions throughout the brain and body. As a hormone and neurotransmitter, oxytocin has a large role in the physiological process of childbirth and lactation. Additionally, oxytocin plays a key role on the formation of maternal bonding, and further extends its importance in human social attachment and behaviours. (Magon & Kalra, 2011) It's influence stems from an evolutionary function.

Evolutionary

[edit | edit source]Oxytocin has a key role in mammalian social behaviour, with an evolutionary function from reproductive behaviours to coping with stress. Oxytocin is most well-known for its role in reproductive and maternal behaviours, with evidence demonstrating OT to be released during sexual arousal and orgasm, childbirth and lactation. (Young & Zingg, 2017) Such behaviours are also linked to that of maternal and social bonding and affiliation behaviours, which in turn are vital in the safety and continuation of a species. Furthermore, much like cortisol to the 'fight vs flight' response, oxytocin has been associated with the 'tend-and-befriend' stress response. The surge of OT release drives the individual to 'tend' to and protect their offspring and themselves, alleviating stress and promoting safety, whilst 'befriending' to establish a social network in which they may maintain this safety. (Taylor et al., 2000) This response has been suggested by researchers to promote the survival of species, and thus serving an evolutionary function. (Taylor et al., 2000)

Physiological

[edit | edit source]OT has both central and peripheral functions throughout the human body. When released into the body, OT induces contractions of the uterus during labour through a positive-feedback system, while also stimulating milk ejection through the milk let-down reflex. (Young & Zingg, 2017)

Additionally, evidence has found increased OT plasma levels in the cerebral spinal fluid upon physical intimacy, sexual arousal and orgasm, as well as OT receptors in both female and male genitalia (see Figure 2). (IMagon & Klara, 2011) Such findings suggest OT plays a preparatory function of sex, as well as facilitating reproductive behaviours and pair bonding.

Within the brain, OT shares a close relationship with vasopressin, which somewhat performs as OT antagonist, despite sharing a similar molecular structure. Both neuropeptides are released by the hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary gland, and are implicated in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis, a mechanism aroused by psychological stressors. (Quirin et al., 2011) Where vasopressin levels rise, oxytocin levels are seen to decrease, as with an increase in oxytocin levels correlates with a decrease in vasopressin levels. Such a correlation relationship will be further discussed later in this chapter.

Psychological

[edit | edit source]Oxytocin has demonstrated the facilitation of trust, empathy, bonding and relationships, as well as social affiliation and cognition. It has been implicated as a key role in romantic love, working closely with vasopressin and the dopamine system to make leave feel rewarding (De Boer et al., 2012, Feldman, 2017) It is released by and motivates feelings of social affiliation, physical intimacy and social support in times of psychological distress.

Intranasal oxytocin: Endogenous vs. exogenous

[edit | edit source]The effects of endogenous (internally made) oxytocin have been researched for the last century, but there is still limited but growing research on the effects of exogenous (externally administered) oxytocin. While intravenous administered oxytocin has been well long used to help induce childbirth and lactation, the nasal form is still being explored. Despite its popularity as the intravenous form, and the growing potential as a nasal spray, the current literature and research yields discrepancies in the efficacy of IN-OT as a medical treatment.

How does intranasal oxytocin affect emotion?

[edit | edit source]While much of the research emphasises the role of oxytocin on social behaviours, to understand such mechanisms we must also consider the emotional processes that underlie them, due to the social nature of humans. This section will discuss the current literature on and effects of intranasal oxytocin on several aspects of emotion.

Emotional recognition

[edit | edit source]Oxytocin has been dubbed the 'moral molecule' due to evidence demonstrating its potential to enhance emotional recognition, and therefore empathy. (Zak, 2011)

A study conducted by Campbell and colleagues (2014) aimed to test oxytocin's influence on emotional recognition among healthy adults, particularly between age cohorts, due to recognised decline in emotional perception accuracy with age. Having conducted a double-blind design, they administered intranasal oxytocin (IN-OT) to two groups of healthy adults, either old (60+) or young (18-30), and found improved emotional recognition levels in men in the older cohort when compared to the placebo group. While their results yielded no difference in emotional recognition for women or those in the younger cohort, this is consistent with the literature which has found both younger age and women to have higher levels of oxytocin, compared to older age or men respectively.

These results have been supported by many other studies, with growing support of OT enhancing the processing of socially relevant information, and thus improving social cognition. (Bernaerts et al., 2016)

Emotional regulation

[edit | edit source]Due to its well-know role in social behaviours, it is no surprise that of oxytocin has been found to have a key role in emotional regulation and stress. While endogenous oxytocin has cortisol reducing properties, IN-OT has also been found to have the same stress buffering effects. Heinrich and colleagues (2003) demonstrated this effect in a study with a double-blind placebo-control group, where participants either had oxytocin or the placebo, and additionally had social support from a friend or were alone in a preparation task. Results found that those who had received the IN-OT had experienced an anxiolytic effect, with social support resulting in suppressed cortisol levels, and the combination of both resulting in the significantly lower cortisol levels, anxiety and increased calmness. (Heinrich et al., 2003) Similarly, Ditzen and colleagues (2008) conducted a study in which they had couple engage in a conflict discussion, acting as the stressor and increasing cortisol levels. As a double-blind placebo-control design, one group was given the nasal spray containing oxytocin, whilst the other was given a placebo prior to the discussion, and with cortisol levels taken throughout the experiment. The results showed that those who had received the IN-OT compared to the placebo had significantly reduced cortisol saliva levels, as well as an increased use of positive communication as opposed to negative behaviours, thus supporting IN-OT as independently capable of protecting against stress.

Furthermore, there is also evidence of a dampening effect of IN-OT on amygdala reactivity to fearful faces.

Sociability

[edit | edit source]The most well-known function of oxytocin is its role to facilitate prosocial behaviour and enhance social cognition. Elevated oxytocin levels have been associated with greater chances of 'seeking out' social support in times of need, relative to the 'tend-and-befriend' response. (Cardoso, 2016) In a now well-known study, Kosfeld and colleagues (2005) tested trustworthiness after administration of intranasal oxytocin, and found that administered IN-OT resulted in increased levels of trust and trustworthiness in complete strangers compared to the placebo. (Kosfeld et al., 2005, Zak, 2011) While this measurement of trust did not measure social capabilities per se, these results demonstrated an underlying mechanism of social interactions and affiliation. (Kosfeld et al., 2005)

Moreover, such research further shines on the critical role oxytocin plays in human social behaviour. This has further enticed researchers to explore the correlations and effects of reduced or deficits in endogenous oxytocin and its receptors. From this, evidence has showcased a correlation with lower oxytocin levels in those with psychiatric disorders characterised by social deficits and impaired trust, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder and schizophrenia.(Amirhossein et al., 2013)

The dark side of oxytocin

[edit | edit source]While oxytocin has been found to increase prosocial behaviours in both intranasal and endogenous forms, these effects have been found to be somewhat inhibited by higher testosterone levels. (Zak, 2011) Paul Zak (2011) discussed in a TedTalk how these elevated testosterone levels were associated with less influence of the prosocial behaviours of oxytocin, and a greater outcome of selfish behaviours. These findings also support the disparities in genders in relation to oxytocin.

Research has also shown individual differences and social contexts to modulate the effects of oxytocin, leading to anti-social behaviours, such as aggression and envy. (Shamay-Tsoory & Abu-Akel, 2015)

Theoretical frameworks

[edit | edit source]Both biological and cognitive approaches in psychology attempt to explain how oxytocin influences emotional and cognitive processes.

Tend-and-befriend theory

[edit | edit source]While oxytocin has demonstrated it's stress buffering capabilities, researchers have suggested its implication in alternative stress response, known as the 'tend-and-befriend' mechanism. (Taylor et al., 2000) This theory was proposed in contrast to the well known fight-or-flight response, as evolutionarily, such an approach to threats would have been too great of a risk for female and their offspring. Instead, this approach proposes females more inclined to release of oxytocin when faced with a threat or stressor, much like the release of cortisol. The hormones would then signal for the individual to protecting both themselves and their offspring (tend), while seeking and establishing social support (befriend) to ensure their safety. This gives a possible explanation as to why intranasally administered oxytocin facilitates greater levels of trust and empathy, while also dampening amygdala reactivity to fearful faces. (Gorka et al., 2015)

Social salience hypothesis

[edit | edit source]While oxytocin may be the product of an evolutionary stress response, the social salience theory emphasises the emotional recognition capabilities. This theory states that the release of oxytocin facilitates greater brain activities in the brain regions used to identify emotional and social cues, therefore improving abilities to identify socially contextual relevant information. (Shamay-Tsoory & Abu-Akel, 2015) This would be in line with studies of IN-OT increasing eye-gaze, emotion recognition accuracy and empathy when compared to control groups.

James-Lange theory

[edit | edit source]The James-Lange theory of emotion stipulates emotion as a product of physiological arousal, and could be related to IN-OT well. In a time of psychological and physiological arousal and distress, one may endogenously release, or intranasally administer OT. This would then reduce physiological responses such as increased heart rate, shallowed breathing and sweating, and thus result in a an emotional state of calm. For a more detailed example, refer to the case study.

|

Case Study Amelia is a 2nd year university student who studies psychology at the University of Canberra. While she thoroughly enjoys her classes and learning, the workload of university was more than she had initially anticipated, resulting in her to struggle throughout her first year of university. However, in her second semester of 2nd year she volunteered as a participant for a research study looking into the stress buffering effects of intranasal oxytocin. She took part in the hopes that it could help her cope with 2nd years more advanced content, and was given a nasal spray and instructed to record the time of administration and her experience of the effects, if any. Right before an exam, Amelia found herself the be sweating profusely, pounding heart and with shallow breaths. She realised that she was becoming stressed and administered the nasal spray. 20 minutes later she recorded a slowing of breath and heart rate, as well as cooling down, and had realised she felt calm. |

How can intranasal oxytocin be used to improve emotion?

[edit | edit source]While there is a growing body of research regarding intranasal oxytocin as a medical intervention, there are still gaps within the research that require filling. Yet despite this, the future direction of IN-OT looks promising, particularly in regard to the treatment of a range of psychopathologies. Due to the significant role on social behaviours and cognition, IN-OT has been particularly focused on the treatment of disorders with social deficits, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), schizophrenia, post-traumatic disorder (PTSD) and anxiety.

One studied has demonstrated IN-OT increased social memory and accuracy in an emotional recognition audio task when compared to placebo in individuals with ASD. (Hollander et al., 2007) Other studies have also looked into the effects of IN-OT on increasing levels of trust and empathy, particularly for the treatment of schizophrenia and ASD, as such disorders are characterised by social challenges such as paranoia and a lack of Theory of Mind.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Intranasal oxytocin has demonstrated significant effects on emotion and emotional processes, and has great potential as a medical intervention. While some evidence yields results suggesting its effectiveness on both healthy and impaired individuals from the use of IN-OT, there is still some inconsistencies in the literature. Therefore, suggesting only those with OT level or receptor deficits would benefit significantly from IN-OT as a medical intervention. Yet, while there are still gaps within the research, more studies and greater consistencies in terms of measuring the concepts involved could lead to a greater understanding of how we can utilise such a versatile hormone for both clinical and possibly everyday use. (Quintana, Smerud, Andreassen & Djupesland, 2018) Though initially considered to be a primarily female hormone, then upgrading to 'moral molecule' and 'bonding hormone', the research on IN-OT has expanded, though there is still debate on the negative implications of oxytocin and its role beyond (pro)social behaviour. However, there is still a great promise in IN-OT as a medical intervention, with further studies required to help solidify and support such research and understanding in a way to achieve the best health outcome.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Emotion (Wikiversity)

- Oxytocin and emotion (Book chapter, 2013)

- Schadenfreude (Book chapter, 2015)

References

[edit | edit source]Cardoso, C. (2016). The Role of Oxytocin in Distress-Motivated Social Support Seeking (Ph. D). Concordia University.

Ditzen, B., Schaer, M., Gabriel, B., Bodenmann, G., Ehlert, U., & Heinrichs, M. (2009). Intranasal Oxytocin Increases Positive Communication and Reduces Cortisol Levels During Couple Conflict. Biological Psychiatry, 65(9), 728-731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.011

Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., & Ehlert, U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological Psychiatry, 54(12), 1389-1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00465-7

Hollander, E., Bartz, J., Chaplin, W., Phillips, A., Sumner, J., & Soorya, L. et al. (2007). Oxytocin Increases Retention of Social Cognition in Autism. Biological Psychiatry, 61(4), 498-503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.030

Gorka, S., Fitzgerald, D., Labuschagne, I., Hosanagar, A., Wood, A., Nathan, P., & Phan, K. (2014). Oxytocin Modulation of Amygdala Functional Connectivity to Fearful Faces in Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(2), 278-286. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.168

Kalat, J. (2018). Biological psychology (13th ed.). Cengage.

Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Zak, P., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435(7042), 673-676. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03701

Magon, N., & Kalra, S. (2011). The orgasmic history of oxytocin: Love, lust, and labor. Indian Journal Of Endocrinology And Metabolism, 15(7), 156. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.84851

Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Domes, G., Kirsch, P., & Heinrichs, M. (2011). Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(9), 524-538. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3044

Nephew, B. (2012). Behavioral Roles of Oxytocin and Vasopressin. Neuroendocrinology And Behavior. https://doi.org/10.5772/50422

Quintana, D., Smerud, K., Andreassen, O., & Djupesland, P. (2018). Evidence for intranasal oxytocin delivery to the brain: recent advances and future perspectives. Therapeutic Delivery, 9(7), 515-525. https://doi.org/10.4155/tde-2018-0002

Shamay-Tsoory, S., & Abu-Akel, A. (2016). The Social Salience Hypothesis of Oxytocin. Biological Psychiatry, 79(3), 194-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.020

Taylor, S., Klein, L., Lewis, B., Gruenewald, T., Gurung, R., & Updegraff, J. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411-429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411

Uvnäs-Moberg, K., & Petersson, M. (2005). Oxytocin, ein Vermittler von Antistress, Wohlbefinden, sozialer Interaktion, Wachstum und Heilung/ Oxytocin, a mediator of anti-stress, well-being, social interaction, growth and healing. Zeitschrift Für Psychosomatische Medizin Und Psychotherapie, 51(1), 57-80. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2005.51.1.57

Young, L., & Zingg, H. (2017). Oxytocin. Hormones, Brain And Behavior, 259-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-803592-4.00056-0

Zak, P. (2011). Trust, Morality and Oxytocin [Video]. Retrieved 10 August 2020, from https://www.ted.com/talks/paul_zak_trust_morality_and_oxytocin.