Motivation and emotion/Book/2014/Guilt and motivation

How does guilt work as a motivator in a social world?

Overview

[edit | edit source]|

Consider this story and after reading it, take a moment to think how you would feel if it happened to you? “You are house-sitting for a friend's parents. It's a pretty easy task actually. All you have to do is eat their food, collect the mail, and feed their bird. Everything is going just fine until one morning you discover that the bird died during the night. You turned the air-conditioning on "high" during the day and forgot to turn it down at night as you had been instructed. The bird died from the excessive cold.” (p. 588)[1] |

This story was used in a study to investigate differences between guilt and shame, and was rated to elicit higher levels of guilt; was this your experience?

The study suggests that one significant difference between shame and guilt is that shame provokes people to think about their personal qualities, and that with guilt the focus is more about their behaviour and specific actions.[2] Considering this focus on behaviour when experiencing guilt, what is the connection between guilt and motivation?

Guilt can be considered either a cognitive or an emotional experience that arises when an individual transgresses against their own standard of conduct or societal norms and considers or believes that they bear responsibility for it.

Motivation "concerns those process that give behaviour its energy and direction”.[3] Motivation can be looked at as a cycle where thoughts influence behaviours, and behaviours drive performance, performance impacts thoughts and the cycle begins again. Each stage of the cycle is composed of many dimensions including attitudes, beliefs, intentions, effort, and withdrawal which can all affect the motivation that an individual experiences.

In the psychological literature guilt is generally looked at in two very different manners. On one hand, the emphasis is on the destructiveness of guilt: it can inflict pain and punishment for an individual's errors, or transgressions against society or mores, and can lead to psychopathology (e.g., depression). On the other hand, it is a motivator for social and cultural acceptable behaviours, and playing by the 'rules'.[4]

Many people believe that the experience or avoidance of negative affective states, such as guilt, illustrate and illuminate many moments of our life. The current understanding of these affective states suggests that they are involved in nurturing an individuals’ adaptation to societal norms, and influencing their decisions, judgments, and attitudes.[5]

It is generally accepted that emotions facilitate the connection between the individual and their environment, and prepare the individual to adapt to situations quickly and effectively. They also communicate, and are communicated, to assist with the regulation of societal mores, particularly in regards to morals and cultures.[6]

Guilt in the individual

[edit | edit source]Appraisal theories suggest that emotions are based on an individual’s interpretation of an event in the context of their beliefs, desires, and goals[7]. Goals are the object of a person's aim or desired results, an ambition or effort; and emotions can help guide and enable an individual through events that influence their goals.[8][9] Connecting goals and emotions is relevant when discussing guilt, particularly when looking at ethical, moral, and cultural mores and behaviours.[10] Guilt can also function as a facilitating emotion to assist with integration of an individual into a community and motivating them to accept and adapt to the societal mores and avoid ostracisation.[11] Emotions like guilt can influence judgements in determining behaviour, motivate cooperative behaviour, and elicit prosocial actions.[12][13][14]

Guilt is considered one of the moral (self-conscious) emotions; others include shame, embarrassment, and pride; and has been likened to an indicator of morality and the social acceptance of certain behaviours.[15]

|

Comparisons with shame and embarrassment

It's a very fine line between guilt, shame, and embarrassment, and it's not one easily negotiated:

The significant difference between shame and guilt is the focus on self with shame and the feeling of responsibility that comes with guilt. A recent view of embarrassment is that it is a less intense feeling of shame and more adaptive and functional. |

In most cases, guilt indicates that an individual has stepped outside of societal mores or personal values, showing them that their actions are jeopardising a goal, for example, being a moral person and is highly linked to morality and the prevention of immoral actions[16][17], and the growth of moral attitudes.[18][19]

When researchers have examined the consequences of guilt by inducing people to transgress, or imagining that they have (as in the Overview story), participants generally will do whatever they can to expunge the guilt and restore their self image.[20] This reflects individuals' needs to reclaim a public image, and they are significantly more likely to act prosocially when another is aware of the situation.[21]

On the other hand, people can experience guilt without having contravened societal mores. For example, it has been shown that an individual may feel guilty from succeeding, when others have failed, even when not responsible for the inequity.[22]

Guilt has been found to motivate individuals, or motivate an individual's actions to alleviate their distress and keep their societal position or relationships, for example, asking for forgiveness or trying to make amends[23]. Research has also shown correlations between guilt and improved interpersonal skills [24], an inclination toward empathy [25], increased self-esteem [26], and improved control of anger.[27]

Some researchers think that the actions motivated from feeling guilty are focused on diminishing the individual’s discomfort irrespective of the ability to repair the damage or elicit forgiveness from the person who suffered the transgression.[28] However, there has been a shift more recently towards studying the relational consequences of a transgression and guilt has been considered an adaptive response to improve social outcomes as it can help the individual to develop connections to others by generating preoccupation for their well-being.[29][30] This view states that guilt is caused by an individual damaging one of their relationships and the resulting emotion is a prosocial occurrence aimed at eliciting actions that help maintain, reinforce and protect important relationships.[31][32] So, it can be said that guilt can maintain group cohesion by eliciting reparatory acts from individuals, for example, helping their neighbours; communicating their affections; and being attentive to the feelings of others.[33][34].

Guilt in society

[edit | edit source]At a societal level, research suggests that guilt may not be sufficient to produce significant change, though it may encourage individuals to act and feel they have done something to alleviate the problem. [35] Researchers have also found positive associations between well-being and prosocial activities, leading them to suggest that guilt-motivated behaviours may be beneficial to the individual. [36] However, sometimes the prosocial behaviours triggered in this way can be made at the expense of others in the society; their focus on making reparations blinding them to their neglect of those around them.[37]

Appraisal and attribution theory

[edit | edit source]Appraisal theory

[edit | edit source]Appraisal theory is a cognitive construct in understanding emotions, and we can extend this to look at how appraisals cause emotions which then triggers an action.[38]. An appraisal is how an individual believes the situation they are experiencing is significant for them and whether, or how, it has implications for their well-being[39] Appraisal theory suggests that these interpretations are what makes an event significant, and generates emotions; and the appraisal of the event is as important as what actually took place, and applies to guilt in that an event occurs and the individual appraises it as something they should not have done, and hence they feel guilt; which would probably motivate them to make reparatory actions.[40]

During appraisal, an individual uses their frontal cortex, memory and decision making, to generate possible outcomes of the situation and how to interact with the people and objects involved in it[41]. Once the appraisal has been made, a positive appraisal generates an approach tendency, and a negative appraisal generates an avoidance tendency [42]. When the individual has determined a course of action, the hippocampal brain circuits, the limbic system.[43], autonomic and endocrine systems[44], and the general arousal systems[45] activate the parts of the brain involved in that course of action and behaviour occurs.[46]

Attribution theory

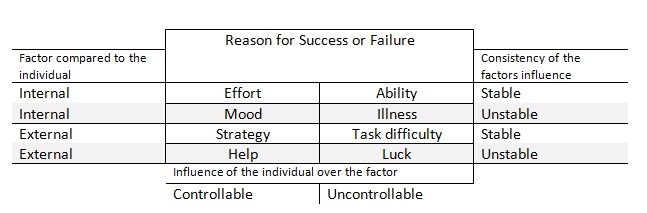

[edit | edit source]In psychology, attribution is the process of how individuals try to understand the cause of the situation. Generally, an individual attempts to explain the causes of an event or situation as either internal or external, unstable or stable, controllable or uncontrollable.

Internal vs. external

[edit | edit source]In an internal, or dispositional, attribution, an individual attributes the cause is due to personal factors such as feelings, traits, or abilities. In an external, or situational, attribution, an individual attributes the cause is due to situational factors.

Example: Peter crashes his RC car. If he believes it crashed because of his driving ability, he is making an internal attribution. If he believes that the crash happened because the track is bad, he is making an external attribution.

Stable vs. unstable

[edit | edit source]When an individual makes a stable attribution, they believe that the cause is a stable, unchanging factor. When making an unstable attribution, an individual believes that the cause is a unstable, temporary factor.

Example: Maria fails an exam. If she attributes the failure to the fact that she always has bad luck, she is making a stable attribution. If she attributes the grade to the fact that she didn’t have much time to study that week, she is making an unstable attribution.

Controllable vs. uncontrollable

[edit | edit source]When an individual believes that they can alter the factor that is causal if we wish to do so, then that is a controllable factor. An uncontrollable factor is one that an individual does not believe they can alter even if they really want to do so.

Example: Shayne comes second in a fun-run. If she attributes the placing to the fact that she didn't try harder, but knows she can do better, she is making an internal controllable attribution. If she attributes the placing to the other runner being better, and that she's not good enough to beat them, than she is making an external uncontrollable attribution.

Table 1.

Descriptions of how attributions interact.

Research has found that causal attributions of an event that lead to an experience of guilt were positively correlated to internal, unstable, controllable attributions (i.e. mood)[47]. People who perceive events as internal and controllable believe that they can alter the situation and experience a more positive outcome; this may be due to a more pro-active attitude and believing that they can bring about and initiate change to deal with their distress.[48]

Physiological considerations

[edit | edit source]As individuals prepare to, and engage in activities, brain circuits activate and the nervous and endocrine systems manufacture and release neurotransmitters, hormones, et cetera; that provide the physiological underpinnings of motivational and emotional states.[49]

The reasons why people are motivated to behave cooperatively are not clear; it has been suggested that the anticipation of feeling guilty is one of the reasons, and they have physiological evidence to back up their claim. [50] It was examined whether the anticipation of guilt elicited cooperative behaviour by assessing the neural structures involved with a participant’s decision to act cooperatively or not.[51] They found that a willingness to cooperate was correlated to activity in areas involved in processing negative emotional states, as well as with the experience of social rejection; when participants chose not to cooperate the areas involved were associated with the processing of reward.

Both shame and guilt do share some common brain circuitry in the temporal lobe, however research has indicated that guilt triggers greater activity in the amygdala and the insula; this increased activity could indicate an attempt to suppress negative emotions, or it could be an affective response.[52] It has also been shown that individuals feeling guilt experience prolonged cardiac sympathetic arousal, increased BAS activity, and higher BIS sensitivity, which indicates that the experience inhibits ongoing behaviour, and elicits reparatory behaviour to alleviate distress (i.e. a punishment cue).[53] This view is backed up by findings that guilt is initially associated with a reduced approach motivation (sympathetic arousal, BIS sensitivity), followed by an increased approach motivation during engagement in prosocial activity.[54]

Introjected regulation

[edit | edit source]According to self-determination theory[55] there are several different levels of motivation, ranging in a continuum from external (nonself-determined) to internal (self-determined); one of the more extrinsic levels is introjected regulation. This level is where an individual is primarily motivated out of a sense of guilt, or being controlled by a feeling that they ‘have to’ or ‘should’ be acting in a certain way.[56] The individual has partially internalised the motivation and is emotionally rewarding themselves for socially appropriate behaviour, and emotionally punishing themselves for poor behaviour.[57] It generally consists of a sense pressure or tension to act in the introjected-motivated manner and the individual could be considered to be carrying society’s instructions and it’s those instructions that are generating the motivation to act.

Self-Determination theory suggests that the most effective way to move from an introjected (guilt-based) style of motivation to a more internal and integrated style is through an autonomy-supportive environment. Autonomy support refers to the attitudes and behaviours of individuals, and societies, to facilitate another’s self-regulation and research has identified some components including understanding another’s perspectives, unconditional regard, supporting choices, and minimising pressure and control.[58]

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Guilt is a painful emotion, and one that individuals tend to avoid, generally by acting in a prosocial or normative manner. The motivation that comes from guilt often works in two distinct manners; one is the avoidance by an individual of any action that may cause guilt, and focusing on acting within their own code of conduct and social norms; the other is performing approach and prosocial behaviours that a person feels will expunge their guilt after they have been 'caught' acting in a manner that transgresses their or society's norms. Neurobiological investigations back up this idea that guilt can motivate individuals to engage in prosocial behaviour, either as a punishment cue, or eliciting an approach motivation to prosocial behavior. Appraisal theory suggests that the way the individual chooses how to interpret an event or another's behaviours, and attribution theory suggests that the way an individual chooses to interpret the cause of an event or another's behaviours, can change they way they feel about the situation and this can change they way they react to it. In general, research has determined that experiencing guilt from the way an individual appraises, or attributes cause to, an event can motivate prosocial behaviours. Self-Determination theory suggests that for the guilt prone they focus more on building their sense of autonomy, and work towards building themselves a autonomy-supportive environment.

- Take home message

Guilt is painful, but it can motivate an individual to act prosocially to feel better.

If you are someone who feels they are guilt-prone and let guilty feelings control your life, build a sense of control and autonomy in your life.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Motivation

- Category:Guilt (Wiki Commons)

- Shoplifting Motivation (Book chapter, 2014)

- Attributions and Motivation (Book chapter, 2014)

- Religiosity and Emotion (Book chapter, 2013)

- Saying Sorry (Book chapter, 2013)

- Criminality (Book chapter, 2011)

- Negative Thinking and Emotion (Book chapter, 2011)

- Shame (Book chapter, 2011)

- Guilt and empathy (Book chapter, 2018)

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Niedenthal, P. M., Tangney, J. P., & Gavanski, I. (1994). "If only I weren't" versus "If only I hadn't": Distinguishing shame and guilt in conterfactual thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 585-595.

- ↑ Niedenthal, et al., 1994.

- ↑ Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding Motivation and Emotion. NJ:Wiley.

- ↑ Carnì, S., Petrocchi, N., Del Miglio, C., Mancini, F., & Couyoumdjian, A. (2013). Intrapsychic and interpersonal guilt: A critical review of the recent literature. Cognitive Processing, 14, 333-346. doi:10.1007/s10339-013-0570-4

- ↑ Carní et al., 2013

- ↑ Carní et al., 2013

- ↑ Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46, 819-834. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

- ↑ Scherer, K.R. (2001). Appraisal considered as a process of multi-level sequential checking. In: Scherer, K.R., Schorr, A., Johnstone. T. (Eds). Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. New York:Oxford University Press, pp 92-120

- ↑ Carní et al., 2013

- ↑ Carní et al., 2013

- ↑ Kroll, J., & Egan, E. (2004). Psychiatry, moral worry, and the moral emotions. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 10, 352-360.

- ↑ Smith, A. (1759). The theory of moral sentiments. Penguin.

- ↑ Frank, R. H. (1988). Passions within reason: The strategic role of the emotions. WW Norton & Co.

- ↑ Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In: Davidson, R.J., Scherer, K.R., Goldsmith, H.H. (Eds.). Handbook of affective sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp 852-870

- ↑ Haidt, 2003

- ↑ Sabini, J., & Silver, M. (1997). In defense of shame: Shame in the context of guilt and embarrassment. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 27(1), 1-15.

- ↑ Smith, R. H., Webster, J. M., Parrott, W. G., & Eyre, H. L. (2002). The role of public exposure in moral and nonmoral shame and guilt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 138-159.

- ↑ Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 665-697.

- ↑ Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2003). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press.

- ↑ De Hooge, I. E., Nelissen, R., Breugelmans, S. M., & Zeelenberg, M. (2011). What is moral about guilt? Acting “prosocially” at the disadvantage of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 462-473.

- ↑ De Hooge, et al., 2011.

- ↑ Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: an interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 243-267.

- ↑ Carní et al., 2013

- ↑ Covert, M. V., Tangney, J. P., Maddux, J. E., & Heleno, N. M. (2003). Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and interpersonal problem solving: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 22(1), 1-12.

- ↑ Fontaine, J. R., Luyten, P., De Boeck, P., & Corveleyn, J. (2001). The test of self‐conscious affect: Internal structure, differential scales and relationships with long‐term affects. European Journal of Personality, 15, 449-463.

- ↑ Leith, K. P., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Empathy, shame, guilt, and narratives of interpersonal conflicts: Guilt-prone people are better at perspective taking. Journal of Personality, 66(1), 1-37.

- ↑ Lutwak, N., Panish, J. B., Ferrari, J. R., & Razzino, B. E. (2001). Shame and guilt and their relationship to positive expectations and anger expressiveness. Adolescence, 36, 641-653.

- ↑ Carní et al., 2013

- ↑ Baumeister et al., 1994

- ↑ Tangney & Dearing, 2003

- ↑ Baumeister et al., 1994

- ↑ Hoffman, M. L. (1997). Varieties of empathy-based guilt. In: Bybee, J. (Eds.). Guilt and children. Waltham:Academic Press., pp. 91-112

- ↑ Baumeister et al., 1994

- ↑ Tangney, J. P. (1998). How does guilt differ from shame?. In J. Bybee (Eds.), Guilt and children (pp. 1-17). San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-012148610-5/50002-3

- ↑ Thomas, et al., 2009

- ↑ Toussaint & Freidman, 2009

- ↑ De Hooge, 2011

- ↑ Reeve, 2009

- ↑ Reeve, 2009

- ↑ Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2006). Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: Support for a theoretical model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(10), 1339-1351.

- ↑ Reeve, 2009

- ↑ Reeve, 2009

- ↑ Holstege, G., Kuypers, H. G., & Dekker, J. J. (1977). The organization of the bulbar fibre connections to the trigeminal, facial and hypoglossal motor nuclei II. An autoradiographic tracing study in cat. Brain, 100, 265-286.

- ↑ LeDoux, J. E., Iwata, J., Cicchetti, P. R. D. J., & Reis, D. J. (1988). Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. The Journal of Neuroscience, 8, 2517-2529.

- ↑ Krettek, J. E., & Price, J. L. (1978). Amygdaloid projections to subcortical structures within the basal forebrain and brainstem in the rat and cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 178, 225-253.

- ↑ Reeve, 2009

- ↑ Tracy & Robins, 2006

- ↑ Wang, Q., Bowling, N. A., & Eschleman, K. J. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of work and general locus of control. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 761-768.

- ↑ Reeve, 2009

- ↑ Chang, L. J., Smith, A., Dufwenberg, M., & Sanfey, A. G. (2011). Triangulating the neural, psychological, and economic bases of guilt aversion. Neuron, 70, 560-572.

- ↑ Chang et al., 2011

- ↑ Michl, P., Meindl, T., Meister, F., Born, C., Engel, R. R., Reiser, M., & Hennig-Fast, K. (2014) Neurobiological underpinnings of shame and guilt: A pilot fMRI study. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9, 150-157.

- ↑ Fourie, M. M., Rauch, H. G., Morgan, B. E., Ellis, G. F., Jordaan, E. R., & Thomas, K. G. (2011). Guilt and pride are heartfelt, but not equally so. Psychophysiology, 48(7), 888-899.

- ↑ Amodio, D. M., Devine, P. G., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2007). A dynamic model of guilt implications for motivation and self-regulation in the context of prejudice. Psychological Science, 18, 524-530.

- ↑ Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). A self-determination theory approach to psychotherapy: The motivational basis for effective change. Canadian Psychology, 49, 186-193. doi:10.1037/a0012753

- ↑ Homey, K. (1937). The neurotic personality of our time. New York: W. W. Norton.

- ↑ Reeve, 2009

- ↑ Deci and Ryan, 2008

External links

[edit | edit source]- Is Guilt a good motivator A Huffington Post blog about the topic at hand.