Motivation and emotion/Book/2013/How to get more sex

Secrets of sexual motivation

Overview

[edit | edit source]

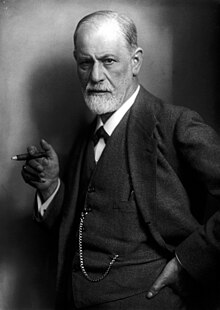

Sexual motivation seems to be a driving force of human nature. As such a fundamental part of the human condition, sexuality has a huge prevalence in popular culture. Evolutionary perspectives of human sexuality favour the theory that women desire a male mate as the protector of their offspring, while males desire more sexual contact to spread their seed and maintain their legacy (Meirmans & Strand, 2010). These ideas place all the focus on reproduction and ignore the other socio-cultural or psychological factors of sexual interactions. We’ve come a long way since then, with pioneering researchers such as Alfred Kinsey studying the sexual practices of both men and women and other revolutionary sexologists, such as Masters and Johnson developing models of the human sexual response cycle, outlining the stages that occur during sexual activity. These researchers focussed less on sexual motivation and more on what happened to humans during sexual arousal. However, when looking directly at sexual motivation, Sigmund Freud famously coined the term of libido as the driving force behind all behaviour, particularly during the psychosexual stages of development. It is a term most commonly used today to refer to sexual drive or motivation. This chapter will focus on the reasons behind what motivates people to have sex, from the basics of reproducing, all the way to more complex psychological motivations and the impact of learned attitudes on influencing sexual behaviour. In an attempt to understand sexual motivation, the following questions will be addressed:

|

Why do people have sex?

[edit | edit source]For most people, sex is a pleasurable activity. Therefore, it seems reasonable that people would like to engage in it. But research has shown that there are many, much more complex motives behind sexual activity. Procreation may seem like the most obvious, but there are also psychologically derived motives that can influence sexual acts. Furthermore, people may be influenced to have sex by values and attitudes learned from their environment. The multitude of reasons that people have sex may surprise you.

Procreation

[edit | edit source]The need to reproduce has long been seen as the most important reason for sexual activity in all species, which makes sense when we look at things from an evolutionary perspective. But with new technology constantly being invented, sex is no longer the primary method of reproduction, even though it may be the most practical and enjoyable! With procreation no longer a driving force behind sex, the evolutionary perspective of sex is now considered outdated and simplistic.

Pleasure

[edit | edit source]Another reason for sex is pleasure seeking. For most people, sex and orgasms feel good, and orgasms have many positive physical and emotional side effects. Some people seek sexual activity outside of relationships purely for the pleasure, rather than intimacy or esteem needs (though these may play a part). The clitoris is an organ designed purely for the purpose of pleasure and even children have been shown to engage in physical touch of their genitals in order to invoke such feelings (de Graaf, Vanwesenbeeck, Woertman, & Meeus, 2011). These findings suggest that sex was not only meant for reproductive purposes, though some might argue that the pleasure sex offers is designed as an encouragement for reproduction. However in studies of sexual motivation, pleasure and reproduction are not the only reasons found for people to have sex.

Psychological factors

[edit | edit source]Freud was notorious for his view that human nature was driven by libido. His theories around the psychosexual stages of development from infancy to early childhood looked at the pleasure seeking nature of humans. He suggested that development through each stage would influence personality later on in life (Cotti & Zarka, 2008). His theories were controversial as they offered little evidence on the efficacy of his theories and made large assumptions on the influence libido has in motivating behaviour. When trying to understand what sexually motivates humans, Freud's theories left large gaps, but they paved the way for more inclusive theories of sexual behaviour.

Learning attitudes toward sex

[edit | edit source]Interesting research on the influence of familial relationships has looked at how people can learn sexual behaviour from their parents. A study on father-daughter relationships theorised that women whose fathers had low involvement in their lives, learned from their cues of disengagement that it may not be worthwhile to invest long term in relationships with males (DelPriore & Hill, 2013). It found that women with disengaged fathers desired to have sex with more men and were more open to sex than females who had more positive relationships with their fathers. Another avenue for learning is something that has an impact on many of our daily lives; television. Viewing sex on television has been shown to shape males and females expectations of sex by increasing acceptance of casual sexual relationships and expectations of peers to be engaged in more sex (Ward & Rivadeneyra, 1999). In turn, these shaped attitudes have acted as predictors of male sexual activity (Ward & Rivadeneyra, 1999). Other studies have also suggested that males and females learn about gender roles and sexual expectations through the viewing of sexually explicit material (Brown & L'Engle, 2009). Increased viewing of this type of material has been shown as an indicator of being more sexually open and engaging in sexual activity earlier in adolescence (Brown & L'Engle, 2009). These findings suggest that we may learn our attitudes toward sex based on the factors within our environment, which can then influence our actual sexual activity.

|

Why is sex good for us?

|

Illness and psychological disorders

[edit | edit source]There are some illnesses and psychological disorders that may increase the desire for sexual activity. Excessive sexual desire can be a symptom of something more serious. Hypersexuality is one such scenario. It involves an overabundance of sexual appetite and can lead to sexual behaviour that is inappropriate or out of control (Kaplan & Krueger, 2010). Disorders that involve hypersexuality are sex addiction, bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Having symptoms of hypersexuality does not necessarily mean that you have one of these disorders, but there has been some debate over whether it can be classed as its own disorder after it's exclusion from the DSM-V. The lay term for hypersexuality is nymphomania. This may sound appealing to some, but it can be very debilitating to sufferers. They may feel deep guilt and shame for their activities, and research has found hypersexuality can lead to an increased risk of HIV and STI's (Kaplan & Krueger, 2010). Other illnesses such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's also have symptoms of hypersexuality (Kaplan & Krueger, 2010). There has been some talk of personality factors as an indicator of engaging in certain types of sexual activities, but this has not been extensively researched (though those with risk taking personality traits are more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour) (Heaven et al., 2003). However looking at abnormal psychology may not the best way of assessing sexual motivation due to the extreme nature of these conditions.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

[edit | edit source]Humans may have desires that are not related to procreation or pleasure influencing them to have sex.

| Intrinsic Motivational Factors | Extrinsic Motivational Factors |

|---|---|

| Pleasure Intimacy Self esteem Stress release |

Duty Social status Security Revenge |

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors have been looked at as a more encompassing way of assessing motivational factors behind sexual engagement. Intrinsic motivations are internally driven desires for doing things, because it is personally rewarding (Ryan & Deci, 2000), e.g. engaging in sex because it is pleasurable for you. Extrinsic motivations are externally driven desires for doing things; to avoid punishment or to get an external award (Ryan & Deci, 2000), e.g. engaging in sex because you feel it is a duty or to get a job promotion. It recognizes that people have many complex reasons for sex, but also includes factors such as procreation (it can be argued that sex for procreation could be an extrinsic factor to make family members happy, or as an intrinsic factor to increase happiness) (Meston & Buss, 2007). This theory is more comprehensive than Freud's psychosexual stages of development or any evolutionary perspectives as it can include learning, and learning certain attitudes toward sex may play a part in defining the intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors of sex.

What determines attraction?

[edit | edit source]So, now we know why people have sex, but this does not necessarily help us in getting more sex. To do this, we need to understand what determines sexual attraction to another person. If we understand this, we can attempt to attract others more readily. There is an abundance of books to guide men and women on how to seduce others and increase their own levels of attractiveness, however many of the factors that sexually attract others are actually subconscious.

|

The emergence of the “pick up artist”

The fame of books such as “The Game” and “The Pickup Artist” have led to an increased popularity in men using seduction techniques to obtain sex from women. These books use strategies to entice women into sex, but do have a basis of psychological factors of attraction that underpin them. With the incredible success of these types of books in popular culture, it is easy to buy into the idea that seduction is as easy as following a number of steps. However, success stories do not necessarily take into consideration that there are underlying influences that underpin attraction other than the seduction technique. So, for the gentlemen who may find that these strategies aren’t working, don’t feel disheartened…it may be due to factors that are completely out of your control. |

Physiological factors

[edit | edit source]The physiological factors that can influence sexual desire and attraction are numerous. Studies have found that hormones, pheromones and body odours all play a part in the subconscious attraction of others. You may see yourself as a great catch but wonder why you do not have men and women flocking to you for sex. It may be because of the physiological factors of attraction outside of your control.

Hormones

[edit | edit source]Within the human body, hormones are produced by the endocrine glands. These chemicals are responsible for making changes within certain organs of the body. Testosterone and estrogen are such hormones that are in charge for the development of the sex organs in men and women. In particular, estrogen in women is responsible for the development of secondary sex characteristics such as pubic hair and breasts and also regulates menstruation. Though there is not a clear link between whether estrogen plays a part in sexual desire, studies have shown that women who have the ability to menstruate and ovulate show greater attraction towards men with symmetrical features (a sign of strong genes)and are more attracted to these features during ovulation (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). Though this does not necessarily mean that higher levels of estrogen increases desire, estrogen's role in regulating these cycles means it may have an implication in attraction. Testosterone is a little more straight forward. It is responsible for the development of the prostate gland and the testes and is actually used in Viagra, a medication that is used to elicit sexual desire (erections) in males (van Anders, 2012). Testosterone is present in higher levels in men than in women and is therefore said to account for the higher sexual desire felt by males (van Anders, 2012).

Body odour and pheromones

[edit | edit source]It may seem logical that bad body odour is a turn off when selecting mates, but research has shown that body odour has a major role in subconscious attraction. Genetically determined molecules which are linked to our immune functioning, called Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules are said to play a part in natural body odour (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). If the composition of a potential mates MHC molecules are significantly different to the composition in our own bodies, we may find ourselves more attracted to them. Reproducing with those of similar genetics may increase the risk of weak genes. The subconscious desire to mate with genetically dissimilar mates (as subconsciously determined by smell) adds greater variance to the gene pool and increases the likelihood of strengthened resistance to genetic disadvantage and weakness (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). Studies have also shown that normally ovulating women tend to be more attracted to the scent of males with more symmetrical features, which is a sign of good genes and fitness for reproduction (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). Those who are not heterosexually inclined have been shown to have different body odour preferences to heterosexuals (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). Pheromones are another aspect of the human body that are thought to be detected through smell. Pheromones are chemicals excreted by the body and are present in humans, animals and even some plants. They can be used to communicate, raise alarms and to attract sexual mates. Though there is some debate about whether humans use pheromones to attract mates, there seems to be some basis for the argument of smell subconsciously attracting mates.

Genetics

[edit | edit source]Though body odour, hormones and pheromones are all part of our genetics, another important aspect of attraction is physical attraction. When asking a person what they find attractive in another, they are more than likely to mention physical features such as eye or hair colour, breast size or facial hair. Attraction to many of these features are due to the evolutionary perspective of sexual motivation; that we are attracted to physical features that are signs of good genes (Buss & Barnes, 1986). Breast size, a smaller waist and wider hips are attractive in females as it suggests fertility (Buss & Barnes, 1986). Facial hair, broad shoulders and a strong jaw are attractive in males as it suggests strength and virility (Buss & Barnes, 1986). These findings have been replicated time and time again, suggesting great strength for this argument. We can change these outward appearances through surgery or other means, but more often than not, we are stuck with what we're born with. It is not all bad news though; research has shown that courtship signals are used as a method of letting another know that we are interested in sex. These typical mating signs in humans include dancing, eye contact and open body language; actions that are involved in what we describe as flirting (Hugill, Fink, & Neave, 2010). We do not need to be genetically privileged or physically enhanced to display these signals, so it is a more inclusive and successful way of increasing attraction.

Celibacy and sexual de-motivation - what turns us off?

[edit | edit source]

Funnily enough, the path to increased sexual activity can be more fully revealed when we look at the reasons people don't have sex. The act of abstaining from sexual activity is known as celibacy (Terry, 2012). To some, the act of celibacy seems to go against the very fibres of our human nature! So, what motivates celibacy and a lack of sexual interest? Often it can be because of health reasons and associated medications, which can leave a person feeling sexually unmotivated (Beck, Robinson, & Carlson, 2013). Hormones can contribute to lowered libido and so can a number of psychological factors and disorders (Davison & Davis, 2011). Vows of celibacy are also common in many religious circles and some people choose to be celibate because of their beliefs surrounding sex before marriage (Stewart, 2006). However, some studies have shown that abstaining from sex can lead to negative health outcomes and a lower quality of life (Terry, 2012). To better understand sexual de-motivation, let's take a closer look at the factors that can lead us to feeling less 'in the mood'.

Medication and health factors

[edit | edit source]Stress and illness may affect one's ability to engage in sex due to weakness or just decreased libido. In addition, some drugs used to treat illness and mental disorders are well known to decrease libido. Anti-depressant, anti-psychotic and blood pressure medications can all decrease sexual interest (Hartmann, 2007). Over-the-counter antihistamines and decongestants can cause erectile dysfunction or problems with ejaculation (Bang-Ping, 2009). Illicit drugs can affect the ability become sexually aroused or maintain an erection (Bang-Ping, 2009). These are not long term effects and can desist once medication is stopped, but for those who rely on these medications long term, it can be very personally stressful and negatively impact their relationships.

Psychological factors and disorders

[edit | edit source]|

Are you a female concerned about your level of sexual desire? Take the test here. |

Sexual dysfunction and mental disorders such as depression can be responsible for feeling less desire (Hartmann, 2007). Sexual dysfunction disorders contribute to having difficulties with sexual arousal, pain or discomfort during sex, and the inability or difficulty in having an orgasm (Zamboni & Crawford, 2002). It can deeply affect relationships because of the difficulties in having enjoyable sexual interactions and can also result in feelings of guilt or shame due to not being able to perform sexually (Zamboni & Crawford, 2002). These feelings can make a person feel afraid or just disinterested in sex because they know it will not be enjoyable for them. The nature of depression means that a person will be naturally inclined to have a decreased libido due to their lack of energy and motivation (Hartmann, 2007). If you feel concerned about your level of sexual desire and feel that it is unnaturally low or high, treatment strategies can be put into place by a professional. Health professionals use self report inventories to assess whether sexual desire is at a normal level. Often masturbation is used to treat those with low levels of desire that aren't able to be explained by the presence of other health factors or mental illness (Zamboni & Crawford, 2002).

Gender differences

[edit | edit source]It may not surprise you that there can be significant gender differences between what attracts men to women and vice versa in heterosexual relationships. In addition, men and women also seem to differ in their reasons for engaging in sex. Some of these are due to evolutionary, biological and learned socio-cultural differences already discussed in this chapter. Of course everyone is different, and not all men and women conform with these findings, especially as research has shown that those engaging in homosexual relationships differ in what they find attractive in potential mates (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). Common differences between heterosexual men and women are outlined in the table below.

| Males | Females |

|---|---|

| Have more sexual partners (van Anders, 2012) Have a more permissive attitude to casual sex (Brown & L'Engle, 2009) Masturbate more (van Anders, 2012) Attracted to younger women with full lips, breasts and hips, smaller waist and shiny hair (Buss & Barnes, 1986) Attracted to women displaying happiness (Tracy & Beall, 2011) More likely to have sex for reasons of pleasure, peer pressure and conformity (Meston & Buss, 2007) |

Less sexual partners (van Anders, 2012) Less permissive to casual sex (Ward & Rivadeneyra, 1999) Masturbate less (van Anders, 2012) More attracted to older men with strong jaws, facial hair, broader shoulders, narrower hips, muscular build, intelligence, high social status and money (Buss & Barnes, 1986) More attracted to men displaying pride (Tracy & Beall, 2011) More likely to have sex for reasons of love (Meston & Buss, 2007) |

How to get more sex?

[edit | edit source]Looking back at the focus questions from the beginning of the chapter, we can see that there are a wide variety of reasons that people have sex. Procreation and pleasure are obvious factors with evolutionary underpinnings that may seem outdated, but are still relevant when we also take into account intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors. These factors can be influenced by values and attitudes we have learned within our environments. Attraction is partially determined by physical features that we deem attractive based on our subconscious view of what constitutes healthy genes, but can also be increased through courtship signals we call flirting. Other issues can impact on our desire for sex, including illness, medication and mental disorders. By taking all of these factors into account, we can find the best way to attract sexual partners and get more sex.

|

How to increase your libido

|

TIPS:

- Increase your libido to get yourself more in the mood.

- Increase the libido of your preferred mate so they will be more interested in having sex. But first, remember to ask their permission. You could do this by asking them to engage in a physical non-sexual activity with you (such as a bike ride) or organising a picnic with aphrodisiacs on the menu (oysters, chocolates and strawberries).

- Don't expect men or women to fall into your lap. Not all of us look like Brad Pitt or Miranda Kerr; we need to put some effort into attracting a mate. Make your intentions known by engaging in flirtatious behaviour (eye contact, compliments and open body language) which have been shown as courtship signals to attract others.

- Choose your preferred mate carefully. Talk to them. By learning of their attitudes toward sex, you are in a better position to gauge whether they are open to the kind of sexual activity you are interested in.

- If you are in a relationship, you could have a dialogue about the amount of sex you would prefer. If you are single, avoid asking strangers outright for sex. Even attractive females can be rejected sexually, and you may be in danger of your request being confused for soliciting sex.

| If you have tried all of these tactics and are still unable to find a willing sexual partner, relax....you may just be trying too hard. Instead, when engaging with others, be yourself and allow things to happen naturally. By the law of averages you are likely to eventually find a willing mate and good things often come to those who wait. |

See also

[edit | edit source]- Motivation and relationships

- Sexual orientation

- Intrinsic motivation

- Extrinsic motivation

- Testosterone and emotion

- Oxytocin and emotion

References

[edit | edit source]Bang-Ping, J. (2009). Sexual dysfunction in men who abuse illicit drugs: A preliminary report. Journal Of Sexual Medicine, 6(4), 1072-1080. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00707.x

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2013). Sexual values as the key to maintaining satisfying sex after prostate cancer treatment: The physical pleasure–relational intimacy model of sexual motivation. Archives Of Sexual Behavior, doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0168-z

Brown, J. D., & L'Engle, K. L. (2009). X-rated: Sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with U.S. early adolescents' exposure to sexually explicit media. Communication Research, 36(1), 129-151. doi:10.1177/0093650208326465

Buss, D. M., & Barnes, M. (1986). Preferences in human mate selection. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 50(3), 559-570. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.559

Cotti, P., & Zarka, M. (2008). Freud and the sexual drive before 1905: From hesitation to adoption. History Of The Human Sciences, 21(3), 26-44. doi:10.1177/0952695108093952

Davison, S. L., & Davis, S. R. (2011). Androgenic hormones and aging—The link with female sexual function. Hormones And Behavior, 59(5), 745-753. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.12.013

de Graaf, H., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Woertman, L., & Meeus, W. (2011). Parenting and adolescents’ sexual development in western societies: A literature review. European Psychologist, 16(1), 21-31. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000031

DelPriore, D. J., & Hill, S. E. (2013). The effects of paternal disengagement on women’s sexual decision making: An experimental approach. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 105(2), 234-246. doi:10.1037/a0032784

Hartmann, U. (2007). Depression and sexual dysfunction. Journal Of Men's Health & Gender, 4(1), 18-25. doi:10.1016/j.jmhg.2006.12.003

Heaven, P. L., Crocker, D., Edwards, B., Preston, N., Ward, R., & Woodbridge, N. (2003). Personality and sex. Personality And Individual Differences, 35(2), 411-419. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00203-9

Hugill, N., Fink, B., & Neave, N. (2010). The role of human body movements in mate selection. Evolutionary Psychology, 8(1), 66-89.

Kaplan, M. S., & Krueger, R. B. (2010). Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of hypersexuality. Journal Of Sex Research, 47(2-3), 181-198. doi:10.1080/00224491003592863

Meirmans, S., & Strand, R. (2010). Why are there so many theories for sex, and what do we do with them?. The Journal of Heredity, 101(1), S3–S12. doi:10.1093/jhered/esq021

Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives Of Sexual Behavior, 36(4), 477-507. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54-67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Stewart, C. (2006). Monastic perspectives on celibacy. In L. Cahill, J. Garvey, T. Kennedy (Eds.) , Sexuality and the U.S. Catholic church: Crisis and renewal (pp. 120-125). New York, NY US: Herder & Herder/Crossroad Publishing Company.

Terry, G. (2012). 'I'm putting a lid on that desire': Celibacy, choice and control. Sexualities, 15(7), 871-889. doi:10.1177/1363460712454082

Thornhill, R., & Gangestad, S. W. (1999). The scent of symmetry: A human sex pheromone that signals fitness?. Evolution And Human Behavior, 20(3), 175-201. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00005-7

Tracy, J. L., & Beall, A. T. (2011). Happy guys finish last: The impact of emotion expressions on sexual attraction. Emotion, 11(6), 1379-1387. doi:10.1037/a0022902

van Anders, S. M. (2012). Testosterone and sexual desire in healthy women and men. Archives Of Sexual Behavior, 41(6), 1471-1484. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9946-2

Ward, L., & Rivadeneyra, R. (1999). Contributions of entertainment television to adolescents' sexual attitudes and expectations: The role of viewing amount versus viewer involvement. Journal Of Sex Research, 36(3), 237-249. doi:10.1080/00224499909551994

Zamboni, B. D., & Crawford, I. (2002). Using masturbation in sex therapy: Relationships between masturbation, sexual desire, and sexual fantasy. Journal Of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2-3), 123-141. doi:10.1300/J056v14n02_08