Motivation and emotion/Book/2013/Attributions and emotion

Attributions and emotion: How do attributions affect emotion?

[edit | edit source]

|

Introduction

Overview[edit | edit source]This book chapter aims to discuss attributions and emotions, how cognition affects our way of seeing the world, and what we can do to fix our negative outlook on things. The history and theory of attributions is discussed, to give readers an in-depth understanding of what attributions are. Knowing about how we make attributions and why is aimed at helping the reader to fully understand themselves so that they can be mindful and aware of it next time they appraise a situation. Emotional states such as depression and stress will be discussed, with some handy self-help tips to guide you as you read. What are attributions?[edit | edit source]Attributions are judgements we make about our environments and the people in them. They are explanations we give ourselves that affect how we think about others (Weiner, 1985). During the early 20th century, Fritz Heider was among the first to explore this topic. He questioned why and how people attributed characteristics to an imagined object such as the smell, colour, texture, shape, and size. (Malle, 2004). People’s desire to explain their life events and interactions is at the core of Attribution Theory (Heider, 1958; Weiner, 1980, 1985, 1986). Questioning the reasons of why things happen, why they did not happen, why they bought something, why are they friends with that person; attributions are the explanation to the cause of an event and we use this to explain our queries (Weiner, 1985, 1986). For example, if you are pulled over while driving you may ask yourself ‘why did I get pulled over?’ The answer to this could be ‘because I was speeding; because I did not see that stop sign; because I was being tailgated’, which makes impatience the attribution used to explain the behaviour. This is your way of understanding the event without having to acknowledge that in reality, you might just be an inconsiderate driver. How does this affect your emotions? Attributions affect our emotions based on our understanding of the outcome of a particular event (Weiner, 1985, 1986). For example, you are angry because you were speeding and were caught; you are sad because you genuinely did not see that stop sign and you still got a fine; you are frustrated because you were being tailgated, which made you speed up, which got you pulled over. Lets consider emotions more closely. What are emotions?[edit | edit source]Emotions are comprised of feelings that make us feel in a certain way in a certain situation (Izard, 1993; Reeve, 2009). Emotions are the result of biological reactions that occur in order to help us adapt to the changing environment or situation we find ourselves in (Reeve, 2009). Our minds (cognition) and our bodies (biological) react to a given stimulus that then produces emotion. Two perspectives that aim to explain what causes emotion are the cognitive and biological perspectives. Cognitive perspective argues that people cannot experience emotion without first having evaluated their situation. This appraisal (good/bad, frightening/boring) elicits an emotional response. Alternatively, the biological perspective argues that people do not need to evaluate their situation before experiencing emotion. We experience the physiological response that then influences our emotions. What makes the biological perspective more plausible than the cognitive perspective is that Izard, Hembree, Dougherty and Spizzirri (1983) conducted studies on infants and their emotional responses. Everyone knows infants are not cognitively developed enough to appraise a situation and decide their emotions based on this appraisal. The fact that Izard and colleagues' (1983) infants smiled at a high pitched voice (Reeve, 2009; Wolff, 1969) and displayed anger as a response to pain (Izard et al., 1983; Reeve, 2009), indicates that cognition does not influence emotional causality, but in fact biology does. However there are other theories that argue that a combination of the two systems causes emotion. Buck (1984) put forward this idea that both cognition and biology work together activating and regulating emotion. When considering how attributions affect emotion, the cognitive perspective provides some clues. Attributions are our evaluations of our surroundings and explanations for why things occur - this is considered a part of the cognitive appraisal system. The attributions we place on things in our lives elicit certain responses from ourselves (i.e. an internal attribution: I failed that math test, because I did not study, this makes me upset; as opposed to an external attribution: I failed that math test, because it was too hard (neglecting the fact that you did not study), this makes me annoyed). |

|

Theories of attribution

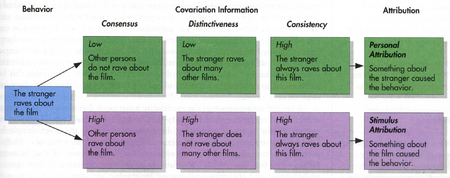

Attribution theories[edit | edit source]Among several theories of attribution, Harold Kelley's Covariation Model and Weiner's Three-dimensional Model will be focused on in understanding how this affects our emotions and how we can use this to improve our lives and general well-being.

|

|

Attribution bias

|

|

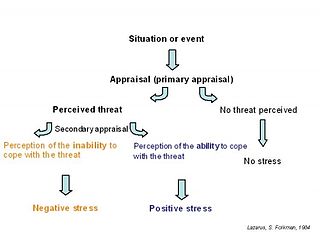

Emotions

Emotional states and attributions[edit | edit source]There are many contributing factors that affect emotional responses. However, the cognitive perspective is more applicable to this chapter, as it argues that it is our appraisals of situations and people that elicit our emotional responses. Several theorists (Lazarus, 1984; Scherer, 1994, 1997; Weiner, 1986) claim that cognitive processing and appraisals are necessary to emotional production (Reeve, 2009). Lazarus (1991a, 1991b; Reeve, 2009) believes that it is the way we understand an event as relating to us personally that creates an emotional response. It is our appraisal of the events affect on our personal safety and well-being that elicits the emotion, rather than the actual event. For example, Lucy has depression. She feels stressed and fearful because the man next to her has a hammer. She is worried he will hurt her. Lucy feels she attracts bad things. However, Lucy may feel differently if she appraised the situation more positively. If Lucy appraises the situation in a more positive manner, she would see that the man is a builder at work. This could make Lucy feel relieved. Therefore, Lucy's appraisal of the man with the hammer could elicit a different emotional reaction based on how she looks at the situation. As previously noted, Weiner (1986; Reeve, 2009) uses the outcomes of life events and the appraisals of these outcomes as the catalyst for emotional reaction. If we attribute success to ourselves and personal skill, we may feel pride and joy. So, if you receive an HD on your book chapter assignment; you attribute this grade to your hard work and dedication to the class, you feel pride. Alternatively if you attribute your HD grade to all the feedback you received, not to your hard work, the emotional response may change from pride to gratitude (Reeve, 2009). Despite the outcome being the same, it is clear that when we attribute a situation differently the emotional response is affected. Depression[edit | edit source]

When someone says they feel depressed they may exhibit the following symptoms:

Depression is the mood state that affects how we perceive the world. Depressed individuals see the negative side of life. Gladstone and Kaslow (1995) conducted a meta-analytic review of the attributions of teenagers and children when depressed. Over 28 studies, they found that higher levels of depression were linked to external and unstable attributions that were made for events that were positive (i.e. receiving a good grade). For events that were negative (i.e. receiving a bad grade), attributions made by depressed individuals were more internal and stable. Depression help[edit | edit source]Awareness:

If you want to change your attributions to be happier, you must be aware. Consciously changing your negative attributions of things to positive attributions helps. If you are upset because you were rejected at your fourth job interview because you believe you are not good, attractive or smart enough for the part; actively recognising this negative attribution would mean you alter it to look at the economic state instead (Sanger, 2011). Stress[edit | edit source]Changing and being mindful of your negative attributions toward situations can helpful if you always feel stressed. Mindfulness is a good way to be aware of your cognitive processes. Once you are aware of them, you are able to change them for the better. If you are aware that you are feeling overwhelmed by your book chapter assignment and you can see that your appraisal of its existence is negative, you can change your thinking to be positive. This will not only decrease your stress levels but also increase your confidence and self-efficacy. Stress help[edit | edit source]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]This chapter aimed to give readers the insight and tools in understanding how their appraisals of life can affect their emotional states. We have defined attributions and emotions, looked at the differing theories and causes of different attributions. Moreover, we have explored the effects depression and stress has on our perceptions and consequently how our perceptions then cause further distress. |

|

For your information...

See also[edit | edit source]Extrinsic Motivation 2013 Book Chapter Intrinsic Motivation 2013 Book Chapter Failure and Happiness 2013 Book Chapter References[edit | edit source]Allen, F. (2010). Health psychology and behaviour in Australia. North Ryde, NSW: McGraw-Hill. American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Fourth edition text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (4th ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. Aron, A., Aron, E.N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of the other in the self-scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 596-612. Bierbrauer, G. (1979). Why did he do it? Attribution of obedience and the phenomenon of dispositional bias. European Journal of Social Psychology, 9, 67—84. Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203—210. Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 745-774. Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 21-38. Gladstone, T. R. G., & Kaslow, N. J. (1995). Depression and attributions in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23(5), 597-606. Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley. Hewstone, M., & Jaspars, J. (1987). Covariation and causal attribution: A logical model of the intuitive analysis of variance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53,(4), 663-672. Izard, C. E. (1993). Four systems for emotion activation; Cognitive and noncognitive development. Psychological review, 100, 68-90. Izard, C. E., Hembree, E. A., Dougherty, L. M., & Spizzirri, C. C. (1983). Changes in facial expressions of 2- to 19-month-old infants following acute pain. Developmental Psychology, 19, 418-426. Jones, E. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (1971). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press. Kassin, S. M., Fein, S., & Markus, H. R. (2010). Social psychology (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Kelley, H. H. (1971). Attribution in social interaction. New York: General Learning Press. Kelley, H. H. (1972). Causal schemata and the attribution process. New York: General Learning Press. Kelley, H. H. (1973). The process of causal attribution. American psychologist, 28(2), 107-128. Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill. Lazarus, R. S. (1984). On the primacy of cognition. American Psychologist, 39, 124-129. Lazarus, R. S. (1991a). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press. Lazarus, R. S. (1991b). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46, 819-834. Malle, B. F. (2004). How the mind explains behaviour: Folk explanations, meaning, and social interaction. London: MIT Press. Munton, A. G., Silvester, J., Stratton, P., & Hanks, H. (1999). “Attributions in Action: A practical approach to coding qualitative data”. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding motivation and emotion (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Roesch, S. C., & Amirkham, J. H. (1997). Boundary conditions for self-serving attributions: Another look at the sports pages. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27, 245–261 Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The 'false consensus effect': An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 279—301. Sanger, S. (2011). Attributional style and depression: How your explanations influence your mood. Retrieved from Psych Central: http://psychcentral.com/lib/attributional-style-and-depression-how-your-explanations-influence-your-mood/0008591 Sapolsky, R. M. (2003). Taming stress. Scientific American, 289(3), 89-95. Scherer, K. R. (1994). An emotion's occurrence depends on the relevance of an event to the organism's goal/need hierarchy. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 227-231). New York: Oxford University Press. Scherer, K. R. (1997). Profiles of emotion-antecedent appraisal: Testing theoretical predictions across cultures. Cognition and Emotion, 11, 113-150. Schwarz, N. (2006). Attitude research: Between ockham’s razor and the fundamental attribution error. Journal of Consumer Research, 33, 19-21. Shaver, K. G. (1970). Defensive attribution: Effects of severity and relevance on the responsibility assigned for an accident. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 14(2),101-113. doi: 10.1037/h0028777 Weiner, B. (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. Morristown: General Learning Press. Weiner, B. (1979). A theory of motivation for some classroom experiences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(1), 3-25. Weiner, B. (1980). Human motivation. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548-573. Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springer-Verlag. Weiner, B. (1992). Human Motivation: Metaphors, theories and research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Weiner, B. (2006). Social motivation, justice, and the moral emotions: An attributional approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. |