Motivation and emotion/Book/2010/Indigenous Australians and motivation

Overview

[edit | edit source]This chapter explores motivational psychology within Indigenous Australians. This is far from an easy topic because of the lack of dedicated psychological literature to date. Indigenous psychology only became a teaching requirement within the psychology curriculum in Australia during the 2000s and there are still limited resources on this topic. This is, in part, because there are few Indigenous psychologists and social science researchers. Much of current Indigenous research work pertains to Aboriginal health and social issues, and not necessarily to specifically understanding motivational psychology. Nevertheless, this chapter seeks to identify some motivational psychology groundwork to improve on the psychological understanding of the impact of European settlement on Indigenous Australians' motivation and values.

- Focus questions

- What are the traditional values and motivations of Indigenous Australians?

- What are the contemporary values and motivations of Indigenous Australians?

- What are the motivational differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian cultures?

- What kind of impact has European settlement had on influencing or affecting values and motivations within Indigenous Australian cultures?

Historical context

[edit | edit source]

- It was estimated that Indigenous Australians first arrived on the Australian continent around 68,000 years ago. This was a period in time when Australia was closer to Indonesian shores and Tasmania was still apart of the mainland.

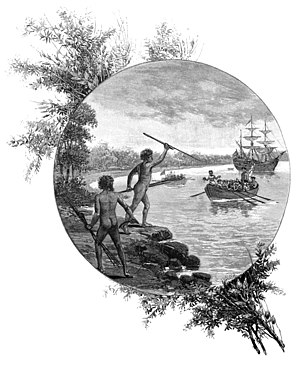

- Around 1606, Dutchman Willem Janszoon sailed to west coast Australia. Janszoon was the first European to meet with Indigenous Australians, where he discovered their semi-nomadic hunting and gathering behavioural habits (Broome, 1994).

- In 1788 the First Fleet arrived in Australia. Indigenous Australian political structure was far different from European political structure, as a result, a cultural gap formed between Indigenous Australians and Europeans.

- Lack of cultural understanding and acceptance lead to violent interactions between the two cultures. Many Indigenous people were slaughtered defending territory, family and cultural beliefs (Broome; Clancy 2004 & Kauffman, 2000).

- Introduction of feral animals and plants added to the devastating loss in native wildlife and habitat destruction. The arrival of foreign species meant that new diseases were introduced, to which Indigenous Australians had no naturally immunity (Colley, 2002).

- 1869 saw the removal of Indigenous Australian children from their families. These children later became known as the Stolen Generation.This period greatly added to the cultural gap already formed at the time (Broome).

- In 1967 a referendum allowing Indigenous Australians to be recognised as Australian citizens was accepted throughout the Australian population (Murphy, 2008).

- 1991-2000 saw the endorsement of the Declaration for Reconciliation (Kauffman, 2000).

- 2000 to 2010 saw the Australian government issuing a public apology for the wrongful acts in the past, such as the stolen generation. Today, there is more acceptance and acknowledgment of the Indigenous Australian culture (Bretherton & Mellor, 2006).

|

Aboriginal/Indigenous

Comes from Latin word ab origine, meaning "from the origin or beginning". Have prior or historical ownership of a land, maintain parts or all of their distinct traditions and associations with the land. Aborigines differentiated in some way from the surrounding populations and dominant nation’s culture. |

Traditional values and motivations of Indigenous Australians

[edit | edit source]

The power of Dreaming on Indigenous motivations, beliefs and life

[edit | edit source]Traditional values and motivations within the Indigenous culture are conveyed through Dreaming. This narrative styled law reflects an understanding of truth, goodness and life values. Some of these values include equality, justice and the importance of family and community. Dreaming can be seen as a form of extrinsic motivation, in the sense that if these cultural values and expectations are achieved, then a person will be rewarded in the spirit world. From a non-Indigenous perspective, dreaming can be interpreted, as a religion that motivates and encourages a particular style of thinking and living within the world. This style of thinking is unique and spiritual. There are behavioural and cognitive motives that can be characterised by certain rituals within this spiritual religion, that have been preserved and passed down through Indigenous generations. Some examples of these rituals include ceremonial dances and dream time stories (Colley, 2002; Howard, Thwaites & Smith, 2001; Kauffman, 2000 & Stasiuk & Kinnane, 2010).

|

Motivation

An internal state that arouses, directs and encourages individuals towards some form of goal (Lei, 2010). |

Importance of storytelling in reflecting motivations and values

[edit | edit source]|

Summary of 'The Bat and the Butterfly' dreaming story "A young man abducts a woman, and keeps her as a prisoner in a cave. Her family is not able to rescue her. As a final resort she turns into a butterfly and escapes. When her captor turns into a bat to chase her he is driven back into the cave by the hunters in the girl's family". The lesson to the listeners of this story is that however talented you may be, when you behave like a coward and don't follow society's laws then you may be banished to live as another form forever in the darkness. This story also explains the origins of the bat and the butterfly. Stories such as these highlight values and beliefs the mold a society. Dreaming stories act as social models of how individuals are expected to live. The stories create awareness and direct behaviour that is influenced by environmental, social and cultural elements. For the video interpretation of "The Bat and the Butterfly" and other dream time stories click here |

Stories from the Dreamtime are extremely complex and sacred, as such, the full meaning is only understood within Indigenous culture itself. For the non-Indigenous population the surface meaning is only explained. Therefore, on the surface, dreaming stories help explain the processes that are involved in creating the world, while also acknowledging all living forms and spirits that inhabit the worlds surface, for example the "Bat and the Butterfly" story explains the creation of bats and butterflies. Dreaming stories also draw on values within the tribal regions they are told in. As such, many stories exist that reflect the totemic belief systems and environmental history of the surrounding land (Stasiuk & Kinnane, 2010). Indigenous Australians are motivated to achieve these values and cultural expectations. The bat and butterfly story teaches the lesson of respect for people. As selfishness and greed can result in social and spiritual repercussions. (Chur-Hansen, Caruso, Sumpowthong & Turnbull, 2006; Colley, 2002; Howard, Thwaites & Smith, 2001 & Kauffman, 2000).

Spirituality

[edit | edit source]Spirituality is a key feature within the Indigenous Australian dreaming and culture. The concept of spirituality is forged around the land, self and community. Spirituality is used as a motivation for health and well-being, where the mind, body and spirit are connected in sickness and healing. All of which ultimately creates purpose and meaning for life and death as it incorporates past, future and present experiences (Kauffman, 2000 & McLennan, 2003).

Dreaming and spirituality are believed to be forms of psychological resilience within the Indigenous culture. For instance, Indigenous Australians who were part of the stolen generation, where they were acculturated from their Indigenous culture, were found to be more susceptible to mental illness than culturally-connected Indigenous Australians. In addition, McLennan's (2003) study suggested that higher levels of stress within Indigenous Australians at that time was related to their difficulty adapting to this changing social structure. Recent studies suggest that dreaming can create opportunities for Indigenous Australians who are experiencing cultural dislocation or stress to reconnect to their ancestors and spiritual aspects of their culture. This connection is highly motivating and significant to their identity and well-being (McLennan). By redeveloping this spiritual bond, McLennan found mental illness to decrease. Stress levels lowered and there was a stronger ability to cope. McLennan's study highlights the potential importance of spirituality in maintaining a sense of purpose and connection to Indigenous identity and cultural beliefs, all of which seems to be a source of motivation in regard to psychological survival (McLennan).

A contemporary link to Indigenous Dreaming, in the aspect of helping to develop meaning and direction in one's life, can be seen within the narrative style therapies that have been employed within counselling settings. Found to be very successful, narrative knowing is based on the idea of making sense of the world by telling stories, which individuals are surrounded by in everyday life. Similar to the ideas behind Indigenous dreaming, the narrative is a representation of knowledge, culture, family, life and living. Both the narrative therapy and dreaming emphasise collectiveness and collaboration. Individuals are members of a network and society, which can be interpreted as family, therapist or community type networks. Ultimately, both cultures use narrative style to externalise problems in an expressive and collective nature in order to find solutions (Percy, 2008).

|

Refocus Box: "The Importance of Dreaming" Margaret Maria Brandl is an educator of Indigenous Australian culture. This is her interpretation of the dreaming; “Land is hallowed for Aborigines in ways non-Aborigines are not even able to guess at. The landscape as we see it is, to Aboriginal eyes, shaped by the tracks of the ancestors beings who have passed through it and over it (and still do). These marks and tracks of the ancestors can be seen in the shape of the hills and valleys, in the rocks and rivers and caves, in the trees and other plants in it and in the animals that live on it. Such ‘tracks’ become patterns in art or song and dances in music and permeate Aboriginal thinking and life at every level. The land is seen as giving constantly of its riches and resources and stories to its Aboriginal people. Like a mother it cares for them. Aboriginals throughout Australia often say, ‘The Land, my Mother’.”(Kauffman, 2000, p. 6) |

Dreaming can be interpreted as a spiritual religion dedicated to the landscape and to the living and spiritual forces. There is a deep sense of respect that transcends from the dreaming, motivating aborigines to understand, acknowledge and pass on the cultural values that are portrayed as sacred and necessary for the survival of this culture (Kauffman, 2000).

Identity

[edit | edit source]de Souza and Rymarz (2007, p. 279) define cultural identity as

the level of identification and integration that individuals have with a particular set of beliefs, practices and way of life. It is critical time in adolescent growth and establishment of cultural identity as an individual moves beyond the perceived control of parents in an attempt to establish ones own identity, which may or may not conflict with community expectation.

History has a strong influence on identity, as cultural identity is highly reliant on being passed down to younger generations by elder community members for its survival. The key feature in keeping cultural identity alive comes down to maintaining a sense of community. It is argued that community offers a variety of basic services and activities. If an Indigenous adolescent is unable to obtain the services or have access to particular activities, there is a high chance he or she will search for another community. This may involve finding new social networks with people that do not share the same cultural beliefs, ultimately resulting in a change of cultural identity and motivational source (de Souza & Rymarz, 2007). Research highlights that urbanised Indigenous children face a loss of identity due to a high degree of dislocation from their cultural heritage. Indigenous identity has evolved overtime as a result of diverse cultural ideologies and practices that have developed in Australia since before European settlement. Urbanised Indigenous people may struggle to reunite with their identity and cultural beliefs. This is believed to be the result of growing urban populations that marginalise the smaller number of Indigenous members in such areas. Loss of identity or culture is thought to be a major contributor for lowing motivation to reconnect with one's heritage (de Souza & Rymarz).

Kinship

[edit | edit source]Kinship within the aboriginal community instills a great sense of togetherness regardless of genetic linkage. Totems are given to individuals in order to create a place for that person within a community. It can link them to other relatives (via links to totems) in different locations. If an aboriginal has no family in other communities then they can be adopted, if their totem links to another family. They are then termed 'brothers' of that family kinship or new community. Kinship can therefore be seen as a form of human support, this is one of the fundamental needs that maintains or allows motivation to grow. Aboriginal Australians can then develop motivation from the degree of kinship felt within their lives (Broome, 1994; Kauffman, 2000).

Contemporary values and motivations of Indigenous Australians

[edit | edit source]Traditional Indigenous values, beliefs and motivations have evolved since the arrival of Indigenous Australians approximately 68,000 years ago. This evolution is a result of diverse cultural interactions in Australia since European settlement. While the basic concept of dreaming is still strong in the aboriginal culture, there are some changes as a direct result of the technological advances in societies and new awareness of other ideologies and cultural beliefs. This is a large area of interest for Fogarty and White (1994), Schwartz and Bilsky (1987) and Schwartz and Bilsky (1990) who came up with a set of psychological human values with the belief they could be replicated cross-culturally (Schwartz and Bilsky). These values included the biological needs of human beings, the necessity of organised social interaction, survival and welfare in terms of group needs and cognitively formed values that strengthen through socialisation, development, and conscious goal setting. From the above human requirements, 11 motivationally associated values were constructed.

- Self-direction: encompassing creativity, freedom, goal choice, independency and curiosity.

- Stimulation: formed from variety and excitement.

- Hedonism: the pleasures and enjoyment of life itself

- Achievement: the successfulness and capabilities that are the result of ambition, motivation and intelligence.

- Power: level of authority, wealth, social influence, public perception and recognition.

- Security: social order, family security, national security, reciprocation of favours, cleanliness, sense of belonging, health.

- Conformity: obedience and self-discipline, respecting elders and honouring family.

- Tradition: respect for customs, humility, devoutness, acceptance of role in life, moderation.

- Benevolence: helplessness, loyalty, forgiveness, honesty, responsibility, truth, friendship, mature love.

- Universalism: broadmindedness, social justice, equality, world at peace, unity, with nature, wisdom, protection of the environment.

- Spirituality: meaning of life, sense of inner harmony, sense of detachment

(Fogarty & White, 1994, pp. 4-5; Schwartz & Bilsky, 1987; Schwartz & Bilsky, 1990).

Fogarty and White (1994) suggest that only items six to eleven relate to Indigenous Australians, as these reflect a more collectivist society. Below are the ten motivational values that were ranked highly for Indigenous university students.

The top 10 Indigenous motivational values were ranked:

- Family security

- Honoring parents

- Health

- Honesty

- Choosing own goal

- True friendship

- Self-respect

- Equality

- Politeness

- Social justice

This list indicates the motivational values of security and family as being the most important item for Indigenous students. Some of the unique motivational values chosen within the Indigenous experimental group included honouring parents, equality, politeness and social justice. These values reflect the sixth to eleventh items of Schwartz and Bilsky (1990) motivational associated values. In comparison, non-Indigenous student values were found to have more individualistic-oriented rankings, such as family, security, true friendship, health, self-respect, choosing own goals, inner harmony, honesty, freedom, mature love and success.

Motivational differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian cultures

[edit | edit source]Over the years, a popular area of investigation within cross-cultural psychology has been the differing cultural perspectives in Australia (Fogarty & White, 1994). The primary difference in perspectives is believed to come from motivational sources such as values (Vernon, 1976, cited by Fogarty & White, 1994). Chur-Hansen, Caruso, Sumpowthong and Turnbull (2006) add that life perspectives differ between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people as a result of cultural heritage and value systems. For Indigenous populations, education and health systems are inadvertently seen as unnecessary or shameful in regard to cultural pride and values. On the other hand, non-Indigenous cultures, such as the dominant white Anglo-Saxon Protestant, highly value education and government health systems. When Indigenous people experience a burden of values between conflicting cultures, which can occur within an education system, then their motivational value system prioritises attitudes and relationships.

Table 1. Some major comparisons between Australian cultures (Harris, 1988, cited by Fogarty & White, 1994, p. 3)

| Indigenous Australian Perspective | Non-Indigenous Australian Perspective |

|---|---|

|

View knowledge as owned and is looked after by particular people within the community. | |

| World view consists of major changes that have already taken place | Knowledge is freely available for those who want it. |

| View of world has religious basis | View of world is more scientific (Westernised perspective) |

| View of environment is more passive, with more focus placed on adapting to the land. | Manipulate the land to benefit personally, e.g. farming and introducing foreign plants and animals. |

| Greater emphasis placed on quality of personal relationship and belief that a perfectly good social system exists. | Westernised concepts of world view and progress entails development, change and control. |

Table 1 presents differing Australian cultural perspectives and focuses on what is more salient for each culture. Traditional Aboriginal cultures place a significant weight on personal qualities and relationships as well as a deep sense of respect for the environment and what it has to offer. Christie (1985, cited by Fogarty & White, 1994) highlights that Australian Aboriginals' survival is highly reliant upon communal cooperation and co-existence. Therefore, motivations tend to reflect a collective nature within Indigenous Australian populations. These motivations differ to white Australian populations which are more individualistically-oriented (Fogarty & White, 1994). Schwartz (1990) developed a 56 item questionnaire to determine motivational values across cultures. The questionnaire was used on Indigenous and non-Indigenous university students. Results found differences in motivational values, providing further evidence to suggest that Indigenous Australian student values reflect collective tendencies.

Contemporary issues facing Indigenous Australians

[edit | edit source]Indigenous families and community are believed to experience greater levels of exposure to stressors that have the potential to be detrimental to well-being. These stressors can include health issues like, mental disorders, death of family members or friends, accidents and disability. There are stressors that relate to relationship breakdowns, unemployment issues, risk seeking behaviours in regard to alcoholic consumption and taking drugs, witnessing violent, abusive acts and associating in criminal activity. Lastly, there are stressors in relation to imprisonment, overcrowded living arrangements, anxiety from pressures to achieve cultural responsibilities and dealing with experiences of racism and discrimination. Current literature highlights the increased likelihood for Indigenous populations to experience one or more of the above stressors than non-Indigenous populations (Fordham & Schwab, 2007, p. 15).

As one of the most disadvantaged cultures in Australia, governments and communities are highly motivated to help form better living conditions and respect for the Australian Indigenous culture. Below are just some of the problems Indigenous populations are still facing today:

- Poor housing

- Lower life expectancy

- Higher unemployment

- Lower incomes

- Lower participation in education

- Higher imprisonment rates

- Higher alcohol consumption rates

Much of these problems are the result of dispossession, racism and lack of understanding from the wider Australian community (Colley, 2002; Fordham & Schwab, 2007; & Kauffman, 2000). As a result of this, governments are trying to find ways of empowering and assisting the Indigenous community. This includes providing better educational opportunities such as giving scholarships to study at universities; creating more job opportunities, introducing government social support systems, like helping individuals who can not find jobs and promoting reconciliation through awareness on Indigenous cultures. (Colley, 2002; & Kauffman, 2000)

Indigenous motivational behaviours within academic settings

[edit | edit source]Another area of differences in motivation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian populations can be seen in academic settings. A study by McInerney (2008) revealed differences in motivations using the personal investment theory. This theory is based on motivational components of achievement goal, which embodies an individual's abilities, mastership and adeptness within life, sense of self, where an individual has purpose, resilience and a self concept, and finally, facilitating conditions, which encompasses external support from people such as family, teachers and friends. According to personal investment theory these key motivational elements assist in the learning processes within academic settings. The study revealed that aboriginal students more often missed school then non-Indigenous students. This is one possible explanation for lower academic levels within this population. McInerney believes this aspect of personal investment theory is linked to negative self concept, where school is not seen as important and therefore motivation to go or participate is low. This may be a direct result of minimal facilitating conditions as defined in the personal investment theory. Results found aboriginal students had lower levels of family support when it came to encouraging school attendance and achieving goals at school. It was further found that Aboriginal students were exposed to higher levels of negative peer influence for things like truancy. Aboriginal student awareness and acknowledgment of lacking social support is believed to be a major contributor for decreasing motivation in academic settings. This is then thought to create a chain reaction effect that later impacts on learning and future opportunities (Bodkin-Andrews, Craven & Martin, 2006 & McInerney, 2008).

Impact of European settlement on values and motivations within Indigenous Australian culture

[edit | edit source]

|

Self-determination

A theory in motivation involved with effectively supporting intrinsic predispositions in regard to behaviours and cognitions |

Motivations can be used as a valuable resource in the face of adversity, it can help people to adapt to environmental, social and personal challenges that arise overtime. When individuals feel helpless or a loss of control, then motivation can act as a driving force to help cope with unpredictable situations. In 1788, a sense of helplessness and loss of external control were real threats to the Indigenous population at the time. The arrival of European settlers changed the Indigenous social system dramatically, as there was a push for acculturation by the Europeans as a solution to the violent political struggles over land issues and for ultimate cultural dominance (Chur-Hansen et al., 2006). It is thought that one of the reasons Indigenous Australians survived this unsettling era, was due to high levels of motivational adaptation through self determination (Colley 2002 & Murphy, 2008). Despite the dispossession, loss and human suffering, the Indigenous population fought for their human and political rights, with the motivational belief that land taken away centuries ago should be returned. Furthermore, there was a push from state and federal governments to have a better understanding of Indigenous culture, society and identity, with the belief it should be preserved not repressed (Colley; Finlayson & Curthoys, 1997 & Murphy).

Activities

[edit | edit source]Cultural differences

[edit | edit source]Can you remember some of the major differences in Indigenous cultures and non-Indigenous cultures?

Here is a quick test to see how much you have learnt.

INSTRUCTIONS: Are the following statements more characteristic of Indigenous or non-Indigenous cultures?

- Land is seen as part of identity, gives feeling of strength and belonging, it is sacred.

- Indigenous OR non-Indigenous

- Culture portrays collectivist tendencies.

- Indigenous OR non-Indigenous

- Has greater levels of support and motivation in academic contexts.

- Indigenous OR non-Indigenous

- Views world in terms of science rather than spiritually.

- Indigenous OR non-Indigenous

- World view and progress entails development, change and control.

- Indigenous OR non-Indigenous

- Uses narrative styled storytelling to explain the earths creation.

- Indigenous OR non-Indigenous

True or false

[edit | edit source]- For any human being, supportive conditions allow motivation to maintain or grow. True/False

- Motivations can assist in dealing with personal challenges and can help an individual to adapt to environmental and social changes out of their control. True/False

- Culture is a static concept, where culture stays the same throughout time. True/False

- According to personal investment theory, Indigenous students show lower levels of motivation to learn and attend school as a result of poor intelligence. True/False

- Some of the motivational values found in Indigenous university students were equality and social justice, which reflect a collectivist culture. True/False

- Indigenous Australians believe the mind, body and spirit are connected to well-being. True/False

- Dream time stories are only created as an entertainment tool for bored remote Indigenous children. True/False

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]- The traditional values and motivations of Indigenous Australians are carried through generations by storytelling.

- Dreaming can be interpreted as a spiritual religion that instills values and social law.

- Spirituality is forged around the land, self and community. It motivates health and well-being through the connection of mind, body and spirit.

- Spirituality and dreaming can build resilience within individuals that are stressed or have mental illnesses.

- Cultural identity relates to the level of identification and integration with a particular set of beliefs, practices and way of living.

- Loss of identity can contribute to lower levels of motivation.

- Kinship, social support and facilitating conditions all influence the growth of motivation.

- Indigenous Australians regard values such as, security, family, health, honesty, goal setting, friendship, self-respect, equality, politeness and social justice most highly within their culture.

- Major differences in environmental perspectives between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

- Indigenous Australians face contemporary issues, some of which includes unemployment, heavy alcohol consumption, lower income and higher imprisonment rates. This is believed to be the result of racism, lack of understanding and insufficient social and government support.

- Indigenous students lack the motivation in academic settings as a result of inadequate social and family support.

- By using motivational resources, such as self-determination, Indigenous Australians have been able to adapt to the changing social and political structure overtime.

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]Bretherton, D., & Mellor, D. (2006). Reconciliation between Aboriginal and other Australians: The "Stolen Generations". Journal of Social Issues, 62, 81-98. Retrieved from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy1.canberra.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=14&hid=8&sid=522c642e-6ebd-4d17-9011-241106e2917c%40sessionmgr11

Broome, R. (1994). (2nd Ed.),Aboriginal Australians. Traditional life. (pp.9-21). Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Chur-Hansen, A., Caruso, J., Sumpowthong, K., & Turnbull, D. (2006). Cross-cultural and indigenous issues in psychology. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson & Prentice Hall.

Clancy, L. (2004). Culture and Customs of Australia.Westport, Connecticut, London: Greenwood Press.

Colley, S. (2002). Uncovering Australia. Archaeology, indigenous people and the public. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

de Souza, M., & Rymarz, R. (2007). The role of cultural and spiritual expressions in affirming a sense of self, place, and purpose among young urban, indigenous Australians. International Journal of Children's Spirituality, 12, 277-288. doi: 10.1080/13644360701714951

Finlayson, J., & Curthoys, A. (1997). The proof of continuity of native title. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Studies ,18,1-15. Retrieved from: http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/ntpapers/ntip18.htm

Fogarty, G.J., White, C. (1994). Differences between values of Australian aboriginal and non-aboriginal students. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 25, 394-408. Retrieved from: http://eprints.usq.edu.au/963/1/Fogarty_White_Values_Abor_and_non-Abor_1994.pdf

Fordham, A.M., & Schwab, R.G.J. (2007). Education, training and indigenous futures CAEPR policy research: 1990-2007. Center for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research the Australian National University. Retrieved from: http://www.mceecdya.edu.au/verve/_resources/Education_Training_and_Indigenous_FuturesCAEPR_Policy_Research_1990-2007.pdf

Howard, J., Thwaites, R., & Smith, B. (2001). Investigating the roles of the indigenous tour guide. The Journal of Tourism Studies, 12, 32-39. Retrieved from: http://www.jcu.com.au/business/idc/groups/public/documents/journal_article/jcudev_012838.pdf

Kauffman, P. (2000). Travelling aboriginal Australia. Discovery and reconciliation. Flemington, Victoria: Hyland House.

Lei, S. A.(2010). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: evaluating benefits and drawbacks from college instructors' perspectives. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 37, 153-160. Retrieved from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy1.canberra.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&hid=15&sid=81b39a7f-0b57-40bf-bfad-ba0ab7b6f30c%40sessionmgr10

McInerney, D. M. (2008). Personal investment, culture and learning: Insights into school achievement across Anglo, Aboriginal, Asian and Lebanese students in Australia.International Journal of Psychology, 43, 870-879. doi: 10.1080/00207590701836364

McLennan, V. (2003). Australian indigenous spirituality and well-being: Yaegl community points of view. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 27, 8-9. Retrieved from: http://search.informit.com.au.ezproxy1.canberra.edu.au/fullText;dn=167230324255510;res=IELHSS

Murphy, M.A. (2008). Representing Indigenous self-determination. University of Toronto Law Journal, 58, 185-216. doi: 10.3138/utlj.58.2.185

Percy, I. (2008). Awareness and authoring: the idea of self in mindfulness and narrative therapy. European Journal of Psychotherapy and counselling, 10, 355-367. doi: 10.1080/13642530802577109

Schwartz, S.H. & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 550-562. Retrieved from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy1.canberra.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=14&hid=17&sid=2ef25792-1c7a-4564-b8de-ddce1f58edf9%40sessionmgr14

Schwartz, S.H. & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a theory of the universal content and structure if values: Extensions and cross-cultural replications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 878-891. Retrieved from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy1.canberra.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=12&hid=17&sid=2ef25792-1c7a-4564-b8de-ddce1f58edf9%40sessionmgr14

Stasiuk, G., & Kinnane, S. (2010). Keepers of Our Stories. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39, 87-95. Retrieved from: http://search.informit.com.au.ezproxy1.canberra.edu.au/fullText;dn=473744275853755;res=IELHSS

External links

[edit | edit source]- Pressing Problems - Gambling Issues and Responses for NSW Aboriginal Communities. Retrieved from http://www.olgr.nsw.gov.au/rr_pp.asp

- Dust Echoes - Ancient Stories, New Voices. The Bat and the Butterfly and other dream time stories. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/dustechoes/dustEchoesFlash.htm

- Glossary. Retrieved from http://www.glossary.com/reference.php?q=Aboriginal}}