Appraising Emotional Responses

— Explaining Events

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

What happened? Why did it happen? How does it impact my goals, values, and beliefs?[1] How important is this to me? Are my goals advanced or thwarted? What could be lost? Who is responsible? What can I do now? These are some of the questions that naturally flash through our minds as we first notice, and then reflect on the various important events in our lives. We naturally appraise events in an effort to explain our losses. We also appraise events to define the problem that has to be solved by the coping strategy we adopt.

Objectives

[edit | edit source]| Completion status: this resource is considered to be complete. |

| Attribution: User lbeaumont created this resource and is actively using it. Please coordinate future development with this user if possible. |

The objectives of this course are to help you:

- Recognize when you are experiencing an emotional event,

- Pause, analyze, and assess that event,

- Determine what that event means to you,

- Identify alternative responses to that event,

- Choose an effective response,

- Respond constructively to the event.

The words assessment, judgment, analysis, reflection, meditation, consideration, and re-thinking can all describe the thoughtful consideration of events, actions, and alternatives described in this course.

This course is part of the Emotional Competency curriculum. This material has been adapted from the EmotionalCompetency.com page on appraisal, with permission of the author.

If you wish to contact the instructor, please click here to send me an email or leave a comment or question on the discussion page.

Analyzing Events

[edit | edit source]When we suffer an important loss, we naturally seek to attribute blame and identify alternative responses. We can blame ourselves, others, the environment, chance, all of these or none of these. We examine our sense of justice as we decide if the event and actions were fair or unfair. We consider what we can and what we cannot change. We look to the past, present, and future. Whether we realize it or not, we begin to grieve for the loss.

When an important event occurs we are inclined to solve the emerging problem or seize the new opportunity. Assessment is the work of defining the problem. It is the first step in finding a solution. We can begin to imagine new possibilities.

What is at Stake?

[edit | edit source]Our ever-vigilant senses scan a continuous stream of information across the environment and rapidly judge what is important and what is unimportant. We quickly orient our attention toward observations that are relevant based on our personal judgments of what we hold to be interesting or important. Some of this happens instantly and involuntarily. For example, the startle response is involuntary and serves to draw our attention to loud noises and other unexpected disturbances. Surprise is an emotion like the startle response that includes a more complex cognitive evaluation; surprise can be spoiled by anticipation, but startle cannot be suppressed. Fear also draws our attention to potential threats quickly and often involuntarily. To protect us against physical threats, our emotional brains are wired to defend even before we comprehend. Our more careful analysis can help us sort out true dangers from false alarms.

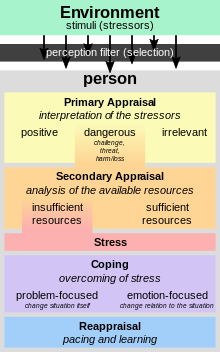

The first appraisal decision is to determine if the event we observed is relevant to our values, goals, beliefs, self, or motivations. If the event is not relevant then we have no stake in the outcome and the event does not elicit emotions or induce stress. We don't interrupt our present activities to attend to these irrelevant events. But if our safety, goals, beliefs, self-concept, or needs are threatened, the event is appraised as important; we interrupt our activities, and attend immediately to the situation. Emotions and their accompanying stress serve to interrupt our routine activities and focus our attention on the most urgent and important situation. Accompanying physiological changes may prepare us to react quickly. The specific emotion that results depends on the nature (plot) of the appraisal. The strength of the emotion depends on our appraisal of the importance or impact of the event. For example, we may be having a routine conversation when someone makes a remark we find offensive. The offense is likely to make us angry because we appraise it as unjust and harmful. If we appraise it as only a mild insult, we may become irritated or annoyed. These are the mildest forms of anger. If we appraise it as a strong insult, we may become incensed, outraged, or livid. These are strong forms of anger. If we appraise the offense as not personal, not credible, not threatening, or not serious we can always decide not to take the bait. Here we can choose to ignore the provocation and avoid a dominance contest.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Notice the next time your anger arises.

- Pause before reacting to this anger. Count to ten if this helps.

- Reflect on what specifically has made you angry. Seek to identify the injustice that has provoked your anger.

- Determine what is at stake?

Loss, Threat, or Challenge

[edit | edit source]Relevant events often involve an actual loss that occurred in the past or present or a potential future loss. Harm and loss describe damage that has already happened. This is a loss that occurred in the past and may still have relevance in the present. Threat refers to a potential future harm or loss. A challenge describes the decision to overcome obstacles and reduce a threat or attain some opportunity. Richard Lazarus proposes[2] that loss, threat, and challenge represent three distinct types of stress and associated coping strategies.

Choosing Options

[edit | edit source]Once an important event is recognized, we can direct our attention toward reducing or mitigating the impact of the loss and its accompanying stress. The coping strategy we choose will depend on our analysis of the situation, including the nature of the event, the time available, and the resources we can apply to reducing, preventing, or overcoming it. We have an opportunity to create new possibilities for what can be.

Appraisals and Reappraisals

[edit | edit source]Multiple appraisals take place over time. Our emotional brain instantly calculates a response to important events before we can engage our cognitive thoughts. Even after we notice our gut reactions, our first thoughts may not fully consider all that has happened, all of the consequences and implications, and all of the evidence and factors contributing to the event. Over time we can reflect on the event and reappraise it. This may alter our response, change our beliefs, modify our goals, or cause us to reexamine our values. For example, you may decide after a long period of reflection that you blamed others unfairly for some incident and now you would like to apologize to them.

Somatic Markers

[edit | edit source]How we feel influences the decisions we make. Our mind consults our body along with our brain.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Notice the next time your anger arises.

- Notice how the anger makes you feel. Can you identify a physiological response?

- Pause before reacting to this anger. Count to ten if that helps.

- Reflect on what specifically has made you angry. Seek to identify the injustice that has provoked your anger. Identify who or what you hold blameworthy.

- Determine what is at stake?

- Reassess the validity and importance of that injustice.

- Consider the range of responses available to you.

- Consider the short-term, mid-term, and long-term consequences of each alternative response.

- Choose the response that will have the best long-term outcome. Often this is a calm, thoughtful and perhaps candid response.

Emotions Reveal Appraisals

[edit | edit source]Emotions interrupt and alert us to important events. They are accurate indicators of what we truly regard as important. The core relational theme of each emotion is constant; if we know the emotion we know the theme that evoked it and the story it tells. Because our emotions depend on our appraisals, knowing the resulting emotions can tell us a lot about the thinking that went into the appraisal. Emotions help us read minds; they provide valuable clues to what is truly important to us and to others. For example:

- We become surprised because the event was unexpected. Therefore we had no foreknowledge or forewarning of the event.

- We are afraid because we perceive the threat of imminent danger. What did we observe? Why does it represent a threat?

- We are anxious because of an uncertain threat. What are we worrying about?

- We become angry because we blame someone for an unjust loss. What is the loss? What goal is thwarted? How important is it? What is our sense of justice? Why do we judge their behavior as unjust? Why do we choose someone to blame?

- We feel guilty because we have failed to meet the another's standard of behavior. What standards were not met? Who values those standards? Are the standards well founded?

- We feel shame because we failed to meet our own standards. What is the standard? Is it well founded? Does it support our values? Did we do our best?

- We gloat when we are pleased about another person's mishap. Why do we enjoy seeing their mistake? Why did we gloat rather than feel compassion?

- We hate when we dislike others enough to blame them for our own troubles. What is the true cause of or troubles? Why do we dislike them? Why don't we respond with empathy and compassion? Why do we blame others?

- We are sad because we have suffered a loss. What did we lose? Why is it important to us?

- We become depressed when we lose hope. What caused us to lose hope?

- We envy someone because we want what they have. Who do we envy? What do they have? Why do we want it? Why do we believe it is valuable? What does that tell us about our motives, goals, and values?

- We are jealous because we fear we are unloved. Why do we feel unloved? What does that tell us about our self?

- We become disgusted when we encounter something toxic. What do we find toxic? Why?

- We are happy because we are progressing toward a goal. What is the goal? What do we regard as progress? Why is the goal important?

- We are proud because we are feeling good about ourselves. What did we do that we judged as worthy? Is it worthy? Is this a genuine pride with some substantial and significant basis, or is it a false pride based on an inflated ego or an unworthy goal? Does it improve our stature or only our status? What does that tell us about our values? Is this pride or hubris?

- We are relieved when a threat has passed. What was the threat? What were we in danger of losing? Why do we perceive it as valuable? How was the threat avoided or overcome?

- We are hoping for the best. What is the basis of our optimistic outlook?

- We are in love! Who do we love? Why do we resonate together? Why are we attracted to them? Why do we care about them?

- We are grateful for the unselfish kindness toward us. Why do we value the gift or consideration?

- We pity someone; we feel compassion for them. Why are we moved by their suffering?

- Ambivalence reveals unresolved conflict between two or more goals. What goals are conflicting? What values can resolve the conflict?

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Notice the next time you feel some emotion.

- Pause before reacting to this emotion. Count to ten if this helps.

- Reflect on what specifically elicited this emotion.

- Identify the emotion.

- Determine what is at stake?

- Reflect on your values.

- Reassess the validity and importance of what is at stake.

- Identify what you can change and what you cannot change.

- Consider the range of responses available to you.

- Consider the short term, mid-term, and long-term consequences of each alternative response.

- Determine what you ought to do.

- Choose the response that will have the best long-term outcome. Often this is a calm, thoughtful and perhaps candid response. You may choose to simply notice the emotion and allow it to pass without allowing it to cause stress to you or others.

Further Reading

[edit | edit source]Students interested in learning more about appraising emotional responses may be interested in the following materials:

- Lazarus, Richard S. (May 4, 2006). Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. pp. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0826102614.

- Damasio, Antonio (September 27, 2005). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Penguin Books. pp. 336. ISBN 978-0143036227.

- Wright, Robert (August 8, 2017). Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment. Simon & Schuster. pp. 336. ISBN 978-1439195451.

- The Nature of Emotions, Plutchik, R, The American Scientist, Volume 89, Issue 4, 2001

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ This material is adapted from the EmotionalCompetency.com website with permission from the author.

- ↑ Lazarus, Richard S. (May 4, 2006). Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. pp. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0826102614.