Ancient Codes of Law

| Subject classification: this is a law learning projects resource. |

| Educational level: this is a research resource. |

|

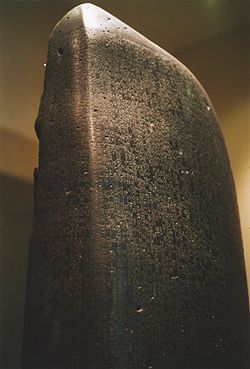

The Code of Hammurabi is a well-preserved law code of ancient Mesopotamia, dating to about 1754 BC, and was enacted by the sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi, with partial copies existing on a 7.5 ft (2.3 m) stone stele and various clay tablets. The Code comprises 282 laws, with scaled punishments, adjusting "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth" (lex talionis)[1] as graded depending on social status, of slave versus free man.[2] The three classes of Babylonian society were property owners, freed men, and slaves. For example, if a doctor killed a rich patient, he would have his hands cut off, but if he killed a slave, only financial restitution was required.[3] |

|

Nearly half of the Code deals with matters of contract, establishing, for example, the wages to be paid to an ox driver or a surgeon. Other provisions set the terms of a transaction, establishing the liability of a builder for a house that collapses, for example, or property that is damaged while left in the care of another. One tthird of the Code addresses issues concerning household and family relationships such as inheritance, divorce, paternity, and sexual behavior. Only one provision appears to impose obligations on an official; a judge who reaches an incorrect decision is to be fined and removed from the bench permanently.[4] A few provisions address issues related to military service. |

|

The Code was arranged in orderly groups, so that all who read the laws would know what was required of them. It has been seen as an early example of a fundamental law, regulating a government — i.e., a primitive constitution.[5][6] The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that both the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence.[7] The occasional nature of many provisions suggests that the Code may be better understood as a codification of Hammurabi's supplementary judicial decisions, and that, by memorializing his wisdom and justice, its purpose may have been the self-glorification of Hammurabi rather than a modern legal code or constitution. However, its copying in subsequent generations indicates that it was used as a model of legal and judicial reasoning.[8] |

Contents |

Notes

|