Wikiversity Law Reports/Gramophone Co v Shanti Films

| This is a Wikiversity Law Report. |

In this case, AIR 1997 Cal 63, the High Court of Calcutta decided on the important question of difference between the assignment of copyright (Sections 18, 19) and licensing of a copyright (Sections 30) under The Copyright Act, 1957. This landmark judgment appropriately differentiates these two modes, and further ascertains India’s position by having an overview of the UK judgments on the issue of assignment and licensing. I will discuss this case in a structure where, first I will provide an factual overview of the case, then briefly discuss issues upon which the court deliberated, thirdly discuss at length the decision of the court, which will include paragraph wise analysis of the ruling. Penultimate, I will discuss importantly the significance of the decision on the film, music, literary (industry) etc., and lastly provide a comparative analysis from the US perspective, to understand the similarities and differences in the law relating to assignment and licensing of a copyright in India and US.

Background

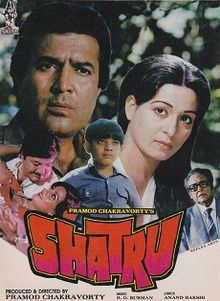

[edit | edit source]The Gramophone Co. of India Ltd., is the plaintiff who filed suit for grant of relief for the acts of infringement of copyright against the defendants (Hereafter referred as ‘Plaintiff’)., where the defendant no. 1 is Shanti Films Corporation, was alleged to have licensed the copyright interest in the film ‘Shatru’ to defendant no. 2 in the suit for publishing cassettes of the film and it was alleged by the plaintiff that such ‘further licensing’ by the defendant no. 1 is illegal and void, owing to the Assignment agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant no. 1 (Gramophone Co. and Shanti Films respectively),through which Shanti Films in agreement in writing assigned the copyright in the sound track of the Film ‘Shatru’ in favour of the plaintiff. The defendants Shanti Films submitted before the court that the agreement in writing was not that of the assignment of the copyright in the film, but it was simply licensing of the interest in copyright of the production and sale of records etc., of the film. This case came before the High Court of Calcutta for the consideration on both procedural issues, and conflicting pleas of plaintiff and defendants, where the former was arguing that the agreement between the parties is of assignment of copyright and the latter was of the opinion that it is a license. Importantly, the civil court passed an order against the plaintiffs and refused to grant them interim relief on the grounds that the plaintiffs have on oath submitted a false case of having paid the royalty of Rs. 27,000 to the defendants, where as in reality the same was not paid to the defendant no. 1, and therefore such interim relief was rejected by the civil court. For the purposes of analysis for this assignment, i will limit my scope to the issues relating to the copyright law, i.e. specifically the ruling of the court on the issue of assignment vs. Licensing and issues related therewith, so to ascertain and analyse the scope and nature of assignment and license of copyright under the statue.

Briefly, as a matter of fact the agreement between the parties stated, “3. (A) The producer hereby assigns and transfers and agrees to assign and transfer to the company absolutely and beneficially for the world...”, “the sole and exclusive right to make or authorise the making of any record embodying the contract recordings, either alone or together with any other recordings...” and “The producer undertakes to execute or obtain the execution of such further assignments or assurances as may be required to safeguard the parties' rights.” These verbatim clauses of the agreement is important for our analysis as the wordings of the agreement played a significant part in High Court’s ruling in the present case.

Issues

[edit | edit source]The issues which were discussed by the court can be divided into the procedural issues, and issues relating to the interpretation of the Copyright Statue’s provisions. I will briefly state both the group of issues, and limit my discussion only to the issues of the copyright. a. When can a temporary injunction under Order 39 Rule 1, Rule 2, be granted? (Please refer to Para. 16 of the judgment) b. Whether the agreement between the parties is that of assignment of copyright or a mere license of copyright? c. What is the determining factor while deciding the nature of the agreement? d. Will the non-payment of the royalty to the defendant no. 1 automatically make the assigned copyright revert back to the defendant? e. Copyright is an actionable Claim or a beneficial interest in the movable property. I will be discussing issues (b), (c), (d) extensively so to provide a strong understanding of the court’s decision on the issue of assignment of a copyright and further in brief have an overview on the issue (e). I will limit myself to the discussion on these issues and exclude the discussion if the first issue.

Ruling

[edit | edit source]The High Court did point-wise analysis of the facts of the case with that of sections 18, 19 and 30 of the Copyright Act, 1957. It was admittedly pleaded by both the parties that the plaintiff is the owner of the original plate and the defendant no. 1 is the owner of the sound track of the film. Plate within the meaning of Section 2 (t) includes any stereo-type or other plate, stone, bock, mould etc., used for printing or reproducing any copies of any work any matrix or other appliance by which records for the acoustic presentation of the work are or are intended to be made.[1] Further it took into consideration the agreement in writing, specifically Clause 3 (A) as mentioned above, and examined the said clause in the light of section 18 and 19 of the statue. Furthermore, the gist of the judgment of the High Court of Calcutta can be found in Paragraph 30, where it held that in order to ascertain an agreement to be that of assignment or a license, the intention of the parties are of paramount significance. In order to gather the intention of parties in normal course, whether they intended to have assignment or a license, (a) the written agreement needs to be critically analysed, and the words therein form the basis of ascertaining the intention of the parties. It further stated that if the terminology such as “assignment” is used in the agreement then the (b) assignment should be readily accepted, irrespective of the royalty paid or not in future. Also the assignment will take effect immediately, and most importantly one needs to focus on the (c) right of recipient to deal with the copyright as owner thereof, by which the right destroy the copyright at his one volition; any of which, if can be gathered, assignment can be readily accepted.[2] These three factors in the courts opinion are determining factors to decide between assignment and licensing, and points (b) and (c) are required to be analysed in case there is difficultly deciding in the point (a). Emphasising on two important judgements with other judgements cited by the parties, the court relied on two important judgments of i) Chaplin v. Leslie Frewin (Publishers) Ltd. (Court of Appeal)[3] and ii) Dhararam Dutt v. Ram Lal,[4] where in the Chaplin case it was held that “even if the words "grant" or "assign" are not used, the intention to assign may appear from the context.” In the Ram Lal case the divisional bench of the Punjab High Court held that “the real meaning of an agreement, rather than the particular choice of words of the parties, has to be looked into in determining whether there is only a license or there is an assignment of copyright.” In Paragraph 31 the High Court after analysing both the precedents and the provisions of law came to the conclusion that the Plaintiff has made out a prima facie case of assignment for the reasons, i) there is no restriction or any compulsion or any stipulation or the grant is not conditional on whose occurrence the assignment will take place, therefore it is not a partial assignment. Importantly the most significant factor of the ruling was that it took into consideration the words chosen in the agreement which were "hereby assigns and transfers... absolutely and beneficially for the world." Therefore the courts came to the conclusion that there was assignment within the meaning of section 18 read with section 19 and the defendants have involved in copyright infringement. The balance of convenience was held to be in the favour of the plaintiff and hence the temporary injunction was granted by the court.

Let us now consider the significance of the decision and then further have a comparative analysis of the India’s position with that of the United States.

Significance

[edit | edit source]Assignment of a copyright (Sections 18, 19) and Licensing of Copyright (Sections 20) give rise to different sets of rights, and intermixing or considering them synonyms will have significant effects on the parties to the agreement and raise serious policy considerations, which if not addressed appropriately can lead to severe effects on the copyrighted works and on the owners of such copyrighted works, giving rise to ambiguity in rights of owners and eventually increase in litigation. This case is a landmark judgment to the extent that it differentiates clearly both the modes of transfer of copyright/interest in copyright and is in conformity with the provisions of the act, where it is mandatory for both an assignment and the license to be in writing, and in case of dispute, by the virtue of this decision the courts are required to gather intention of the parties from the wordings of the agreement. Also this judgment is prospective, as it provides two other factors, namely the assignment should be readily accepted and will take effect immediately and does not depend on the royalty paid or not, and it does not make an assignment invalid or void if such royalty is outstanding. Secondly and most importantly one must look into the rights of recipient to deal with the copyright as the owner, by which the right to destroy the copyright at his one volition, will prove the assignment of the copyright. This judgment therefore caters the need of the dynamic nature of copyright law and substantially differentiates the two modes i.e. Assignment and licensing of the copyright.

Comparative Analysis with the United States perspective

[edit | edit source]The US Copyright Act, 1976 deals with the copyright in United States, where specifically section 101 of the act leads the provision of ‘transfer of copyright ownership’, where by assignment, mortgage, and exclusive license or by any other conveyance, alienation the copyright ownership may be transferred. Section 101 also clearly recognizes that a “copyright owner” is not limited to owner of all the rights but includes owner of any single “particular right”. Major controversy arises in the interpretation of the two modes of transfer i.e. Assignment and Exclusive License. The analysis of Patry[5] and Nimmer[6] on the issue seem to take this position that both assignment and exclusive license are synonyms to each other, and they argue that in both of these modes there is a outright transfer of ownership. Party on copyright, “A Copyright owner may transfer copyright ownership by assignment or exclusive license, the two being synonymous.”[7] This reading of section 101 read with section 201(d) by Patry and Nimmer is problematic to the extent that it dissolves and override the principle of license non-transferability, and what differentiates assignment and license is the fact that in assignment of a copyright the copyright wholly or partially is transferred to other party. Usually it is transfer of all the essential rights which the statue provides, and it is subjected to the agreement to the contrary. In licensing however there is transfer of only one particular interest or sets of such interest in copyright by the owner, and licensee cannot further transfer it to any third party. This issue was highlighted in the case of Gardner v. Nike[8] in 2002 by the influential 9th circuit court and for the matter of fact Party and Nimmer argue their position as mentioned above criticizing this case. Gardner answered a very important legal question of whether the provisions of section 101 override the established rule of license non-transferability. They concluded in negative, by ruling that the statue confers a “FORM OF OWNERSHIP” on exclusive licenses and section 201 (d) (2) extends to such owners all the “Protection and Remedies "accorded. The owner of the copyright by this title does not have power to transfer as the same is outside the scope of “the protection and remedies”. Therefore, if the owners of such exclusive licences are given complete ownership rights it will be against the rule of non-transferability of license and wrong.

Thus the Ninth Circuit read the statue as using the term “ownership” to refer to an interest that did not include all powers generally associated with the title. Thus for example powers related “to defend any suit or litigation as an owner” and it does not confer complete ownership rights.

Indian law on the other had draws a clear distinction between the assignment of a copyright and licenses, and there is no such ambiguity in reading of section 18, 19 (assignment of copyright) and section 30 (licenses). In the light of this discussion Gramophone case further clarifies the provision of the statue and therefore is significant to the extent that the agreement between the parties and the wordings therein have the most important consideration while deciding the question of assignment or license of copyright.

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Para. 17 of the Judgment; Section 2(t) of the Copyright Act, 1957

- ↑ Para. 30 of the judgment

- ↑ (1965 (3) All ER 764)

- ↑ AIR 1953 P&H 279

- ↑ Patry on Copyright Thomson Reuters/West, Rel. 5, 3/2010

- ↑ Nimmer on Copyright

- ↑ Patry on Copyright Thomson Reuters/West, Rel. 5, 3/2010 pp. 5:101, 5-190

- ↑ http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1412&context=btlj