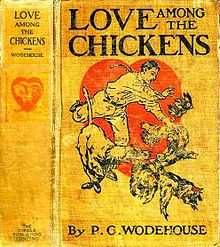

P.G.Wodehouse

The popularity of Wodehouse characters is widely recognized as names like Jeeves are usually used without quotation marks. Jeeves, the masterpiece of Wodehouse, is most delightful in his role as “a gentleman’s personal gentleman”. Wodehouse would have claimed no originality for Jeeves as a broader type. What Wodehouse could have claimed as his own patent with Jeeves was the successful use of him as a recurrent, charming, funny and credible agent in plot-making.

The achievement of P.G.Wodehouse is too formidable to be ignored, but his place in the literary history of the 20th century is not easy to evaluate. The approach of reviewers usually has been to accept the Wodehouse books as products of pure fantasy. ‘I cannot criticize, I can only laugh’, wrote one reviewer.

Two types of novels

[edit | edit source]Wodehouse once said, ‘I believe there are two ways of writing novels. One is mine, making a sort of musical comedy without music and ignoring life altogether; the other is going right deep down into life and not caring a damn…’. Wodehouse didn’t regret in taking up the first way, for thousands of readers all over the world continue to approve his unmatched ability to stir ceaseless mirth.

Plots

[edit | edit source]The Wodehouse farce plots are highly complicated and Wodehouse took immense trouble in handling them ingeniously. Other good authors, having achieved plots one stage less involved, would feel perfectly justified in their artistic consciences to allow their denouncements to start through a coincidence or act of God. Wodehouse, in the Jeeves stories, used Jeeves as an extra dimension, a godlike prime mover, a master brain who is found to have engineered the apparent coincidence or coincidences.

Comparison

[edit | edit source]There are elements of similarity between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and P. G. Wodehouse in the formulation of the stories. The adventures of Jeeves, as recorded by Bertie Wooster and the adventures of Sherlock Holmes as recorded by Dr.Watson have close similarity in patterns and rhythms. Sherlock Holmes and Jeeves are the great brains, while Dr. Watson and Bertie Wooster are the awed companion-narrators bungling things if they try to solve the problems themselves. Also, the high incidence of crime in the Wodehouse farces, especially the Bertie/Jeeves ones, may be an echo of the Sherlock Holmes stories. As a result, literary appreciation for the most part takes the form of articles in which Wodehouse characters are treated without reference to their creator, as in the body of criticism which has grown up around Sherlock Holmes, which depends on the convention that nobody ever mentions Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The character of Jeeves

[edit | edit source]Jeeves, in most stories, is the rim of the wheel and the hub, the plotter and the plot. Bertie sometimes insists on handling problems in his own way. Jeeves, in his background planning, cannot only allow for Bertie’s mistakes; he can estimate their extent in advance and make them a positive part of the great web he himself is spinning. And he is so confident of his success that he will often take his reward before his success has actually happened and before his reward has been offered.

It is generally agreed that however William Shakespeare’s mind might soar into the fanciful for the supernatural, he continued to keep his feet firmly on the ground. Similarly, whatever the local conditions in the Wodehouse country, it is not the realm of nonsense absolute. All comedy refines, selects and exaggerates. It is possible to conclude too hastily that in Wodehouse the process is carried so far that contact is lost with the world of experience, its persons, its motives, its dilemmas and its appetites. The characters will be found to exist well within the permissible limits of artistic presentation.

Wodehouse characters arouse laughter not because they are outside the human family but because they are so plainly within it. Wodehouse’s country, like any other country, has its own fancies and conventions and it has its own idiom. But the realm to which it belongs is the realm of English comedy. It is governed quite as firmly as that of Fielding or Jane Austen by the philosophy of life downright practical, and even earthly. The test that the comedian must apply is the test of his own observation and knowledge of life. It is by applying it in his own way that he makes comedy an art and performs his function of correcting unworldly illusions and exposing what is pretentious and unreal.

Autobiographical Elements

[edit | edit source]We find more of the Wodehousean personal identity hidden in the character of Bertie Wooster than in any other Wodehouse puppets. Richard Usborne, the critic, thought that Bertie Wooster was Wodehouse’s main surrogate outlet for the self-derogatory first person singular mood. The name Wooster is significantly close to Wodehouse. Bertie, in portions of his background and many of his attitudes, is the young Wodehouse. Bertie Wooster’s relationship with Jeeves seems to be a public school arrangement, easy for Bertie, though surprisingly acceptable to Jeeves. Bertie is extremely lucky to have a servant who understands his master’s weaknesses and forgives them.

When Hilary Belloc wrote that Wodehouse was the best writer of English alive, he was paying tribute not only to his control of strange imagery, but to his discipline in telling a complicated story quickly and clearly. Here is an example:

“Tuppy Glossop was the fellow, if you remember, who, ignoring a lifelong friendship in the course of which he had frequently eaten my bread and salt, betted me one night at the Drones that I wouldn’t swing myself across the swimming bath by the ropes and rings, and then, with almost inconceivable treachery, went and looped back the last ring, causing me to drop into the fluid and ruin one of the nattiest of dress-clothes in London.”

Berties hardly ever tries to be funny and he is not a bit witty. He will use a piffling phrase for a lofty sentiment or a lofty phrase for a piffling sentiment. He bubbles and burbles, innocent and vulnerable. Shakespeare, in ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, wrote: “The lunatic, the lover and the poet/ Are of imagination all compact”. These three types cannot keep their feet on the ground; or their minds on the subject. Bertie is three parts lunatic; He sometimes loves. In his wild imagery he is not far off from being a poet.

Wodehouse once said: “The three essentials for an autobiography are that its compiler should have had an eccentric father, a miserable misunderstood childhood, and the hell of a time at his public school and I enjoyed none of these advantages. My father was as normal as rice pudding, my childhood days went like a breeze with everybody understanding me perfectly, while as for my schooldays at Dulwich, they were just six years of unbroken bliss.”

Aunts in his novels

[edit | edit source]The aunts in Wodehouse’s novels have a striking similarity to the masters in his school stories. Scratch Jeeves, we find an aunt below the surface. The aunt, he says is the elder, and the elder always wins in the end. It is true that one of Wodehouse’s most enduring convictions is that it is extremely difficult to shake off the habit of deference and obedience at those set in authority over us in youth. Napoleon may have been able to stand up to his old nurse, but only on one of his good days. But the essence of P.G. Wodehouse’s books is successful rebellion by the young against elders.

Wodehouse worked regular and long hours and his smoothest writing has almost always been the result of his most laborious pruning and polishing. After he was created a Knight of the British empire in 1975, he said in a BBC interview that he had no ambitions left. He died the same year at the age of ninety-three. But Wodehouse’s idyllic world will never cease to exist. His books will continue to release future generations from captivity that may be more irksome than our own. He has made a world for us to live in and delight in.