Macro Strategies to Enable Occupation/Leadership & Political skill

Being a project manager really challenges the student to be a leader because they are . . . . sitting on the steering committee and having to . . . . direct and set the agenda. I think that’s quite a big challenge, and I can see for a lot of students it would be challenging, but I think it’s a really good learning curve (Agency Sponsor, Fortune & McKinstry, 2012, p. 269).

This web page written by Tracy Fortune.

Objectives

[edit | edit source]- To explore the notion of political skill/competence/adeptness as conveyed in the literature

- To consider the relationship between political skill and leadership

- To reflect on professional practice (for example, your project based experience) and identify how political skill may be deployed to enhance desired outcomes

Lecture

[edit | edit source]In the lecture we will explore further the qualities and capabilities of leaders.

Please listen to the following short (18 minutes) Podcast - where I interview an occupational therapy manager about leadership and political skill

Learning associated with this week's topic is supported by this online content, a two hour tutorial (face to face/unrecorded) and a two-hour lecture for enrolled Occupational Therapy students.

Politics and political skill

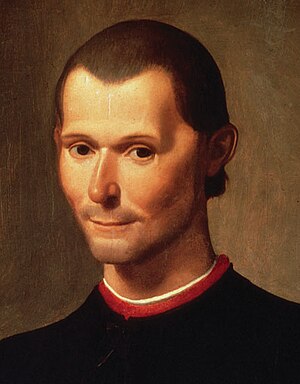

[edit | edit source]No doubt you have heard of the term "machiavellian" - after the Italian political scientist Niccolo Machiavelli. This is not a course in machiavellianism, but a brief exploration of the political context of much of what we do in practice as health professionals.

In their text, A political practice of occupational therapy, Pollard, Kronenburg and Sakellariou (2008) make a distinction between “large P” politics – a ‘defined sphere of human relationships, indicated by terms such as ‘the state”, ‘government’, ‘public administration’ or a political party” (p3) and “small p” politics - the inter-professional relationships, personal needs, and individual motivations that may relate to managerial concerns. Large P politics is what we typically think of when we hear the term “politics”. “The small p reflects the personal rapport on which partnership and practice” depend (p.11). Pollard et al. have developed a reasoning tool – a set of questions they call the pADL (political activities of daily living) framework to help determine the political nature of a situation. The questions relate to understanding a local climate in terms of cooperation and conflict. Politically skilled individuals (usually, but not always, leaders) seem to have an almost innate sense when it comes to picking up on and responding to this climate. Political skill, can however, be learnt.

'Conflict and cooperation are the key elements of all political activity.

Political skill is stated by Perrewe & Nelson (2004) to be evident in individuals’ ability to combine social astuteness with an engaging style that inspires confidence, trust and genuineness. Described by McGann (2005) as an ability to use the knowledge of structures and relationships in organisations to advance key ideas, political acumen might also be thought of as micro-political competence. Morley (2004) describes that this acumen relates to how people compete with each other to get what they want, and how people cooperate or build support among themselves to achieve their ends. Early professional success in most contemporary workplaces I argue (Fortune, Ryan & Adamson, 2013; Fortune, 2012) as have others (Pollard, 2008), directly relate to graduates’ political adeptness. There is also evidence that politically skilled individuals are less likely to perceive work situations as stressful (Perrewe & Nelson, 2004; Harvey, Harris, Harris, & Wheeler, 2007). Evidence indicates that new graduates in occupational therapy are particularly susceptible to stress (Adamson, B., Hunt, A., Harris & Hummel, 1998; Rugg, 1999; Barnitt & Salmond, 2000; Wilding, 2011).

The need to develop greater political acumen was highlighted as far back as 1984 in the national Occupational Therapy Conference keynote by Barker (1984). Other calls to provide educational components in professional programs that develop assertiveness, negotiation skills and organisational awareness are also longstanding (Allen, Graham, Hiep & Tonkin, 1988). We are all political actors to a degree – in that we are operating in a context of cooperation and conflict (whether this be in our family – the parent, negotiating with a very clever 5 year old who needs to go to bed, but doesn’t want to; or the manager of a large company who needs to generate larger profit margins from workers who could care less, to the occupational therapist who needs to broker a satisfactory situation between a family who are not ready for their loved-one to come home yet, and an insistent ward manager who needs the bed for the 3 others still on the waiting list). Griffith (2001) proposed that effective occupational therapists will be those who

- are able to appreciate and function effectively in the political climate in which they are working

- are comfortable with the notion of power and exerting influence

- are assertive

- are good at negotiation and conflict resolution skills

- have the necessary skills to actively influence decision making within the health care team

I propose that because political skill appears to be critical to “effective work performance, there is a need to prepare students in many vocationally oriented programs with this kind of capability before they graduate” (Fortune, 2012, p.612).

Pollard et al (2008) have develop a reasoning tool – a set of questions they call the pADL (political activities of daily living) framework to help understand a local climate in terms of cooperation and conflict. We will explore the pADL framework in further detail in the tutorial.

Here's another set of questions that help you think about 'office politics' - from Career Exchange Career Exchange - There's no need to play dirty to win blogspot

Leadership, political skill and project management

[edit | edit source]

Leaders possess a sense of personal agency and political skill and they use this to take other people on a journey with them. Leaders with an engaging style are able to unite individuals, and form a team that develops a shared vision, working toward a mutually valued goal (Higgs, Ajjawi, McAllister, Trede & Loftus, 2012). Dwyer et. al. (2013) cite Webster, (1999) who says that “project implementation is primarily about people. Only people can produce work and effort so your first concern must be how to lead and motivate” (p.117). A necessary first step in leading is to have awareness of points of potential resistance and conflict. Dwyer, Liang & Thiessen (2019) state that “project managers must understand and acknowledge the political nature of most organizations, especially the influence of key stakeholders” (p 186). Dealing with organizational politics involves firstly being able to see and ‘read’ what is going on. Dwyer, et. al. (2013) cite Stephenson (1985) who argues that "the necessary skills include negotiating and bargaining, urging and cajoling, and coping with resistance (p.184).

Imagine yourself as an OT in a community based service that has seen the need for a new way to work with the community on an occupational issue. You propose a project to scope and establish the new occupational program. Your sense of agency fuels your motivation/intention to act on the need for innovative and effective health strategies to meet the needs of the community. Political skill is then required to: negotiate for scarce resources to implement the program, identifying whom one should most usefully approach, how they should be approached, and then use a range of influence and persuasion strategies to highlight how such a program is in the interest of the community, the organization, and the individuals approached (those who have power). Having the idea is one thing, persuading others and taking them on the journey with you is quite another. Politically skilled individuals, and most leaders, have excellent communication skills. Even if you don’t feel that you are politically skilled at this stage, you will be working from a sound base of ‘intentional communication skills’ developed in this program. This point is nicely made by our interviewee in the podcast.

Tutorial

[edit | edit source]In the tutorial we will be:

- exploring the project context as a ‘site’ of political activity

- identifying elements of conflict and cooperation

- thinking about our own level of political skill and

- considering some key elements of political skill that may enable you to plan and achieve more positive outcomes.

References

[edit | edit source]Adamson, B., Hunt, A., Harris, L., & Hummel, J. (1998). Occupational therapists perceptions of their undergraduate preparation for the workplace. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 173-179.

Allen, F., Graham, J., Hiep, M., & Tonkin, J. (1988). Occupational therapy 1981-1986: Trends and implications. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 35, 155-164.

Barker, J. (1984). Sylvia Docker Lecture. Into the 21st Century: Are we ready? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 31, 98 – 105.

Barnitt, R., & Salmond, R. (2000). Fitness for purpose of occupational therapy graduates: Two different perspectives. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 443-448.

Dwyer, Liang, Z., Thiessen, V. & Martini, A. (2013) Project management in health and community services: Getting good ideas to work. 2nd Ed. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Dwyer, J., Liang, Z., Thiessen, V. (2019) Project management in health and community services: Getting good ideas to work. 3rd Edition. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Fortune, T. & McKinstry, C. (2012) Project-based fieldwork: Perspectives of graduate entry students and project sponsors. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 59,4, 265-275.

Fortune, T. (2012) Should higher education curriculum develop political acumen among students? Higher Education Research and Development, 31 (4), 611-613.

Harvey, P., Harris, R., Harris, K., & Wheeler, A. (2007). Attenuating the effects of social stress: The impact of political skill. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(2), 105-115.

Higgs, J., Ajjawi, R., McAllister, L., Trede, F. & Loftus, S.(2012). Communicating in the health sciences. 3rd Edition. South Melbourne: Oxford.

Stephenson, T. (1985) Management: A political activity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

McGann, A. (2005). The story of 10 principals whose exercise of social and political acumen contributes to their success. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning 9, 5.

Morley, L. (2004). The micropolitics of professionalism: Power and collective identities in higher education. In B. Cunningham (Ed.), Exploring professionalism (pp. 99 - 120): Bedford Way Papers. Institute of Education, University of London.

Perrewe, P., & Nelson, D. (2004). Gender and career success: The facilitative role of political skill. Organizational Dynamics, 33(4), 366-378.

Pollard, N., Kronenburg, F. & Sakellariou, D. (2008) A political practice of occupational therapy. Sydney: Elsevier.

Rugg, S. (1999). Junior occupational therapists' continuity of employment: What influences success? British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 6, 277-297.

Wilding, C. (2011). Raising awareness of hegemony in occupational therapy: The value of action research for improving practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58, 293-299.