Global Perspective

Introduction

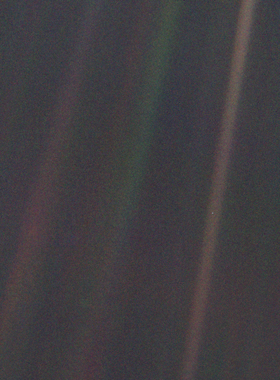

[edit | edit source]Knowledge and technology growth has been explosive, however well-being has stagnated. This presents grand opportunities for humanity. Albert Einstein advised: "We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them." As philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer observed: “Every person takes the limits of their vision for the limits of the world,” therefore it is important for us to expand our vision toward a global perspective. This course explores the prospects of adopting a global perspective to begin to meet the grand challenges. Only a global perspective brings us uncensored realty.

Objectives

[edit | edit source]| Attribution: User lbeaumont created this resource and is actively using it. Please coordinate future development with this user if possible. |

The Objectives of this course are to:

- Quickly survey the Grand Challenges we now face,

- Understand how narrow perspectives have contributed to creating problems,

- Explore how broader perspectives can lead to solutions,

- Introduce specific skills for solving problems by adopting a broader perspective,

- Adopt higher integrating models that change your perspective,

- Outline an approach to solving a particular problem,

- Expand your worldview to encompass the entire world as it is.

This course is part of the Applied Wisdom Curriculum.

The Grand Challenges:

[edit | edit source]Many of the world’s Grand Challenges, the greatest, most pervasive and persistent problems facing humanity, have languished for a long time and may seem immune to analysis and solution. These are the subject of the companion course on the Grand Challenges. An important premise of this course is that adopting a global perspective can help us accurately establish priorities, and can suggest new solutions to these important problems.

If you have not already studied the Grand Challenges course, please take time to read over the Mountains of Problems described there. Give some thought to how a narrow perspective may contribute to those problems and how a Global Perspective can help to identify solutions.

Seeing Through Illusion

[edit | edit source]Each of us face convincing illusions every day that distract us from seeing the full extent of what is. Perhaps the most pervasive and persuasive illusion is that what I see is all there is. To attain a global perspective it is important to recognize these illusions and strive to see through them.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Read the essay Toward a Global Perspective—seeing through illusion.

- Identify the illusions that you have recognized and overcome as you have learned more about the world. These may include childhood beliefs as simple as the Santa Claus and Tooth Fairy stories, or more significant misunderstandings about the diversity and scope of the world, its people, and the universe. What caused you to see through these illusions? How did your worldview change as a result?

- What illusions do you not yet see through? What can you do to see beyond these and expand your perspective?

The Premise:

[edit | edit source]

Problems persist because a narrow point of view has prevailed:

- We often have a narrow focus on economic growth (and economics is a flawed and narrow metric)

- Negative externalities are dismissed.

- We often consider only a short term time frame.

- We often adopt a narrow scope of concern. When we accept a narrow point of view, we are like the blind men examining the elephant. We are each correct within the limited scope of our reference frame, but we are incorrect when a global perspective is adopted.

- Our instincts are tribal. We have evolved to promote in-group cooperation at the expense of competition between group.

- Evidence is denied, delayed, distorted, and disputed.

- We often settle for a narrow definition of success.

- We often make assumptions of unlimited growth.

Externality

[edit | edit source]An externality is an economic impact resulting from your activity that is kept outside the scope of your organization’s financial accounting. Here are some examples.

Owners of coal mines manage several externalities. Coal miners risk death or injury from a mining accident. They can get black lung disease from long exposure to coal dust. Extracting the coal diminishes the supply of a non-renewable resource, and burning coal is dirty. The environmental impact of the coal industry includes land use, waste management, and water and air pollution caused by the coal mining, processing and the use of its products. In addition to atmospheric pollution, coal burning produces hundreds of millions of tons of solid waste products annually, including fly ash, bottom ash, and flue-gas desulfurization sludge that contain mercury, uranium, thorium, arsenic, and other heavy metals.

Air pollution including anthropogenic climate change; water pollution, depletion of the commons, and systemic risk are all important examples of negative externality.

A key skill in attaining a global perspective is to become aware of the externalities of any activity, then take action to reduce impact on others from that externality.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Study the Tragedy of the commons.

- Identify your own activities, such as driving a car, eating meat, cooking dinner, heating your home, turning on the air conditioner, taking out the trash, flushing the toilet, using a string trimmer, protection from the rule of law, living in freedom, and enjoying civil liberties, that create or depend on externalties.

- For one activity identified above, identify the externalties it creates or depends on. Suggest a fair scheme to eliminate, manage, or assign the costs for those externalties.

Economics and Well-Being

[edit | edit source]How similar are economic prosperity and well-being? To answer that question we need to consider:

- Who’s prosperity?

- What level of prosperity?, and

- What does well-being require?

Although Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is not a measurement of the standard of living in an economy, it is often used as such an indicator, on the rationale that all citizens would benefit from their country's increased economic production. Similarly, GDP per capita is not a measure of personal income. GDP may increase while real incomes for the majority decline.

GDP does not measure externalities, including wealth distribution and ecological damage. It also makes no distinction between activities that negatively impact well-being and those that contribute to it. For example, a fatal car crash increases GDP because it requires economic activity to care for the dead and injured, replace the destroyed cars and other property damage, and litigate the various injuries and other damages.

Historically, economists have said that well-being is a simple function of income. However, it has been found that once wealth reaches a subsistence level, its effectiveness as a generator of well-being is greatly diminished.[1] This paradox has been referred to as the Easterlin paradox[2] and may result from a "hedonic treadmill."[1] This means that aspirations increase with income; after basic needs are met, relative rather than absolute income levels influence well-being.

No comprehensive model for attaining well-being is widely accepted. Until such a model emerges, the definition of good from the Virtues course provides a suitable surrogate for well-being. It may be helpful to imagine prosperity in terms of flourishing rather than as opulence.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Part 1:

- Read the essay "Simply Priceless"

- Read the essay "Economic Faults".

- Identify: 1) Ways in which economic prosperity is contributing to your well-being, and 2) Ways in which your well-being is independent of, or even harmed by, economic prosperity.

Part 2:

- Study the good module from the Virtues course and complete the assignment in that module.

Tribal Perspective

[edit | edit source]It is helpful to contrast a global perspective with a tribal perspective, and to acknowledge our deeply routed tribal tendencies.

The book Moral Tribes[3] by Joshua Greene can help us understand our inclinations to automatically react from a tribal perspective, and encourages us to overcome this tendency when controversy arises and we need to adopt a global perspective. The book is briefly summarized below (quotes are from the book.)

Following the organization of the book, it is helpful to draw on three metaphors:

The first of these metaphors is Me versus Us (issues of morality within a group) and Us versus Them (issues of morality between groups). Morality evolved to enable cooperation within groups, but at the cost of competition between groups. Our need for within-group morality is old enough that evolution has provided the “moral machinery in our brains” in the form of intuitive heart-felt feelings of: right and wrong, love and hate, fear and comfort, joy and sadness, loyalty and jealousy, threats and mercy, vengeance and compassion, fairness and anger, and guilt and shame. The morality of our hearts preserves tribal harmony at the expense of global conflict. It is now time when we must augment this moral machinery with new moral thinking that can solve the problems of intergroup cooperation.

The second metaphor is that “The moral brain is like a dual-mode camera with both automatic settings (such as ‘portrait’ and ‘landscape’) and manual mode.” This metaphor illustrates our System 1 (automatic, fast, intuitive) and System 2 (difficult, deliberate, slow) modes of thinking that are more fully described in the excellent book Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. In the chapter titled “Efficiency, flexibility, and the dual process brain” Greene describes how our fast and efficient emotions help us solve everyday problems of cooperation, yet instinctively provide solutions to intergroup problems that are contrary to more rational and deliberation considerations. Sometimes the right thing to do just feels wrong. What is going on here?

The third metaphor introduces the “common currency” required to allow trade-offs among competing tribal values and resolve the conflict between what our hearts and our heads are telling us to do. He chooses “deep pragmatism” (his proposed renaming of utilitarian philosophy) as this common currency. Greene identifies and addresses the many misunderstandings and objections that have arisen to the utilitarian philosophies introduced long ago by Bentham and Mill. As he explains, deep pragmatism provides the answers to two essential questions: What really matters? Who really matters? After an in-depth exploration of these questions, he provides this shorthand answer: “Happiness is what matters, and everyone’s happiness counts the same.”

The automatic settings of our brains quickly solve the moral problems we face every day within our tribe, but we need to switch from automatic to manual mode to deliberately solve intergroup problems from a global perspective. These solutions may not feel right, because they contradict our automatic settings. “The natural world is full of cooperation, from tiny cells to packs of wolves. But all of this teamwork, however impressive, evolved for the amoral purpose of successful competition.” When controversy arises, it is time to switch from automatic mode to manual mode, appeal to the common currency, and reason our way to a solution. “Here we have a choice: We can use our big brains to rationalize our intuitive moral convictions or we can transcend the limitations of our tribal gut reactions.”

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Part 1

If you can obtain and read the book Moral Tribes, that will be ideal. If not, then please view this YouTube video[4] of author Joshua Green sharing ideas from the book.

- Identify the various tribes you belong to. This may include your:

- Community,

- Demographic unit (gender, age, ethnicity),

- Socioeconomic class, Social groups,

- Schools attended,

- Religion, belief systems, life styles, cultural groups

- Political party affiliation,

- Favorite sports teams,

- Sports, hobbies, clubs, special interests, leisure activities,

- Workplace, organization memberships, and other groups and affiliations.

- Identify the global systems you participate in. These may include:

- Voting, and participation in regional, national, and international government,

- Advocating for public policy, especially including policies that establish or restrict the rights, duties, and behaviors of others,

- Attitudes and advocacy regarding human rights,

- Allocation and use of various commons, including: atmosphere, water, forests, wetlands, oceans, fisheries, land, wilderness, minerals, electromagnetic spectrum, and other natural resources.

- Creating externalites.

- Tolerating and valuing customs of other tribes

- Identify attempts to apply a tribal perspective to solving a global problem. (Many examples are listed in the section on Case Studies in the Grand Challenges course.) Describe the situation. What are the various tribal perspectives being advocated? How do these tribal perspectives conflict? Pose the following questions and attempt to answer them. (Notice if answers are proposed from a tribal perspective or from a global perspective.)

- What really matters? (Hint, see: What Matters.)

- Who really matters? (Hint, everyone does, see: Dignity and the Golden Rule)

- Adopt a global perspective and propose a solution based on a global perspective.

Part 2

- Read these Six Rules for Modern Herders.

- Apply these rules to resolve moral controversies.

The Virtues

[edit | edit source]The virtues guide us toward a wise global perspective.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Complete the Wikiversity course on the Virtues.

The General Solution:

[edit | edit source]- Choose Humanity, Preserve Dignity, First do no harm. Advance no falsehoods.

- Seek Real Good.

- Compete the course on moral reasoning.

- Expand the time horizon.

- Expand to consider a global scope

- Internalize the externalities.

- Become aware of any moral instincts arising from a tribal perspective. Assess these deliberately and dismiss them if they are not helpful in this context. Determine how a global perspective can provide a more consistent solution.

- Ask: What really matters? Who really matters? Answer from a global rather than from a tribal perspective.

- Apply a robust theory of knowledge to evaluate the evidence and make well-informed choices.

- Know how you know and insist that others do the same.

- Acknowledge Limits to Growth and incorporate these as design constraints.

- Advance human rights, worldwide.

- Insist on intellectual honesty in yourself and others.

- Employ Systems Thinking (Systems Analysis) to better understand the full extent and causes of the problem, examine interconnections, and design solutions.

- Employ these System Analysis Tools

- Use Quality Management to align efforts with needs.

- Manage redundancy, resilience, and efficiency.

- Integrate symptoms to identify and address common causes.

- Use a prevention-based approach.

- Understand variability

- Reduce waste

- Become Creative in seeking solutions

- Use Wisdom to guide us.

- Use the Twelve leverage points

- Compete the course on problem finding.

- Compete the course on solving problems.

Specific Solutions

[edit | edit source]Apply the general solution described above to selected problems listed below.

- Could adopting a global perspective have prevented us from losing our way along the tobacco road?

- Can the Global Zero campaign succeed in eliminating nuclear weapons?

- Can adoption and pursuit of the Millennium Development Goals reduce poverty and hunger, increase education, improve health, and increase environmental sustainability?

- Can we work to advance human rights, worldwide?

Suggestions for further reading:

[edit | edit source]- Kelleher, Ann; Klein, Laura (2005). Global Perspectives: A Handbook for Understanding Global Issues. Prentice Hall. pp. 240. ISBN 978-0131892606.

- Rosling, Hans (April 3, 2018). Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World--and Why Things Are Better Than You Think. Flatiron Books. pp. 352. ISBN 978-1250107817.

- Greene, Joshua (December 30, 2014). Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them. Penguin Books. pp. 432. ISBN 978-0143126058.

- Azarian, Bobby (June 28, 2022). The Romance of Reality: How the Universe Organizes Itself to Create Life, Consciousness, and Cosmic Complexity. BenBella Books. pp. 320. ISBN 978-1637740446.

Resources

[edit | edit source]- Knowledge to Wisdom — helping humanity acquire more wisdom by rational means.

- Kelleher, Ann; Klein, Laura (2005). Global Perspectives: A Handbook for Understanding Global Issues. Prentice Hall. pp. 240. ISBN 978-0131892606.

- The Power of Outrospection, an RSA Animate by Roman Krznaric

- The World Values Survey is a global research project that explores people’s values and beliefs, how they change over time and what social and political impact they have.

- The Long Now Foundation

- Our World In Data is an online publication that presents empirical research and data that show how living conditions around the world are changing.

- HumanProgress.org presents empirical data that focuses on long-term developments.

- Gapminder seeks to promote a fact-based worldview everyone can understand.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Explaining Economics

- ↑ • Carol Graham, 2008. "happiness, economics of," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Prepublication copy.

• _____, 2005. "The Economics of Happiness: Insights on Globalization from a Novel Approach," World Economics, 6(3), pp. 41-58 (indicated there as adapted from previous source). - ↑ Greene, Joshua (December 30, 2014). Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them. Penguin Books. pp. 432. ISBN 978-0143126058.

- ↑ Joshua Green: "Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them" | Talks at Google