Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2021/Summer/105/Section 15/Marvin Edward Dizor

Marvin Edward Dizor | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Pharmacist |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah (last name unkown) |

| Children | None |

Overview

[edit | edit source]Marvin Edward Dizor was a white pharmacist from Raleigh, North Carolina. During the Great Depression, he dealt with economic and mental health challenges. Dizor was interviewed for the Federal Writers’ Project in 1939.[1]

Biography

[edit | edit source]

Early Life and Education

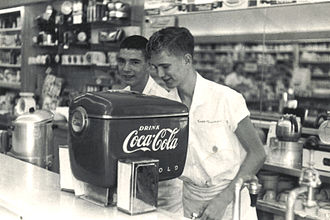

[edit | edit source]Dizor was born in North Carolina. He was raised by his father, a policeman, and mother, a stay-at-home mom. Shortly after graduating high school, he began working at a local pharmacy as it was the only available job. His job at the pharmacy was to clean the building and manage the soda fountain. Through this experience, Dizor became interested in Pharmacology and decided to attend pharmacy school. After saving some money, Dizor attended pharmacy school for nine months but wasn’t able to attain a pharmacy license due to him harassing school officials while being drunk. He had to go through another six months of schooling before he could finally get his license. Once he got his license, Dizor decided to enlist into the Medical Corps during World War I. [2]

Adulthood and Career

[edit | edit source]After the war ended, Dizor returned home. It was around this time when he decided to buy a pharmacy. He knew how to operate one due to his previous experiences, but what he didn’t know was the responsibilities associated with owning one. By becoming a business owner, Dizor encountered a lot of difficulties. He had to follow strict narcotic regulations. Just one mistake and he could end up in prison. To add on, he had to pay several taxes. According to Dizor, the drug business is just “taxes, taxes, taxes until you don’t care whether you hear the word again or not”. Combine this with the fact that he was working constantly, Dizor eventually became fed up with his job. [3]

While all of this was going on, Dizor met and married his wife, Sarah. Even though they loved each other dearly, Dizor’s new mother-in-law was against their marriage. This is because both Dizor and Sarah decided not to have any children. Regardless, Dizor still supported Sarah’s family when they were in need. This financially strained him as the pharmacy was already struggling due to the Great Depression. With this in mind plus the complaints listed in the previous paragraph, Dizor decided to change professions in search of a more profitable career. Unfortunately though, from real state to insurance, all of his business ventures were unsuccessful. Dejected and with no other plan, Dizor returned to his pharmacy. [4]

Social and Historical Context

[edit | edit source]Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914

[edit | edit source]

The Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914 limited the sale of narcotics (opium, morphine, heroin, and cocaine). The act unfairly targeted minorities to discourage the use of narcotics.[5] Because of the act, distributors had to start paying a tax for carrying any narcotics. Furthermore, narcotics could only be given to people who had an actual medical reason. People who used it recreationally or are addicted were denied. The government enforced this law by requiring detailed records of all narcotic sales and by handing out severe punishments. If the act was violated, distributers would lose their license and possibly go to prison.[6]

Taxation During the Great Depression

[edit | edit source]

The Great Depression was an economic crisis that took place in the 1930s. It was triggered by the Wall Street Crash of 1929. During this period, banks failed and unemployment rose.[7] To combat these effects, fiscal policies were implemented. The purpose of fiscal policies is to increase government revenue. One way to do this is by raising taxes. The 1930s were no exception. People during this time dealt with a sharp increase in tax rates. Tax rates on individual income saw the greatest increase during the Great Depression. On top of that, new taxes were implemented. Business owners and all American citizens, in general, struggled even more because of this newly added burden. [8]

Burnout Syndrome

[edit | edit source]Burnout syndrome is a state of being that results from various workplace stressors. It’s characterized by mental exhaustion, detachment from one’s work priorities, and low self-esteem. This syndrome is known to be prevalent among healthcare providers, especially community pharmacists. A 2001 study on community pharmacies found that “39% of pharmacists and 30% of pharmacy technicians exhibited moderate to high levels of emotional exhaustion”. The reason why community pharmacists are at high risk of burning out is because they are responsible for an entire community. They are usually the only provider in the area and have to work nonstop to meet their patients’ needs. [9]

References

[edit | edit source]Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Sedberry, W. B., and Massengill. “Rolling Pills”. Interview. From the Federal Writers Project Papers #3709, Folder 744, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Lesser, Jeremy. “Today is the 100th Anniversary of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act”. Drug Policy Alliance. December 16, 2014. https://drugpolicy.org/blog/today-100th-anniversary-harrison-narcotics-tax-act

- ↑ Spillane, Joseph and William B. McAllister. "Keeping the Lid on: A Century of Drug Regulation and Control." Drug and Alcohol Dependence 70, no. 3 (2003): S5-S12.

- ↑ Field, Anne. “The main causes of the Great Depression, and how the road to recovery transformed the US economy”. Business Insider. September 24, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/what-caused-the-great-depression

- ↑ McGrattan, Ellen R. "Capital Taxation during the U.S. Great Depression." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, no. 3 (2012): 1515-1550

- ↑ Ball, Amanda M., Jennifer Schultheis, Hui-Jie Lee, and Paul W. Bush. "Evidence of Burnout in Critical Care Pharmacists." American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 77, no. 10 (2020): 790-796.

Bibliography

[edit | edit source]1. Ball, Amanda M., Jennifer Schultheis, Hui-Jie Lee, and Paul W. Bush. "Evidence of Burnout in Critical Care Pharmacists." American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 77, no. 10 (2020): 790-796.

2. Field, Anne. “The main causes of the Great Depression, and how the road to recovery transformed the US economy”. Business Insider. September 24, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/what-caused-the-great-depression

3. Lesser, Jeremy. “Today is the 100th Anniversary of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act”. Drug Policy Alliance. December 16, 2014. https://drugpolicy.org/blog/today-100th-anniversary-harrison-narcotics-tax-act

4. McGrattan, Ellen R. "Capital Taxation during the U.S. Great Depression." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, no. 3 (2012): 1515-1550.

5. Sedberry, W. B., and Massengill. “Rolling Pills”. Interview. From the Federal Writers Project Papers #3709, Folder 744, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

6. Spillane, Joseph and William B. McAllister. "Keeping the Lid on: A Century of Drug Regulation and Control." Drug and Alcohol Dependence 70, no. 3 (2003): S5-S12.