Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2021/Summer/105/Section 08/Virgil "Budge" Johnson

Biography

[edit | edit source]Life Story

[edit | edit source]Virgil "Budge" Johnson was a tenant farmer born in 1871 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.[1] His last name came from his father's slaveowners, whom Budge's second wife Rachel worked for post-slavery. Raising his family, with one child from his first wife and five from Rachel, Budge lived in a four-room house on Johnson's land, which was seven miles from Chapel Hill and twelve miles from Durham. His family held membership at Mt. Sinai Baptist Church. In his early life, Budge attended only a few years of primary school at the Piney Mountain School. His children never graduated high school either, but his grandchildren were able to ride the bus to attend Chapel Hill public schools. A superstitious man, Budge believed in ghosts, astrology, "signs," and would perform annual farm tasks on certain days according to the lunar calendar and unique weather patterns. Virgil Johnson died on April 14, 1952 at the age of 80 and is buried in the Mt. Sinai Church Cemetery.

Virgil "Budge" Johnson | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1871 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina |

| Died | 1952 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina |

| Occupation | Tenant farmer |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

Personal Beliefs

[edit | edit source]Politics

[edit | edit source]In a 1939 interview for the Federal Writers Project by W.O. Forster,[2] Virgil Johnson said, "About forty years ago I was voting and they passed a law making the voters explain the Constitution and they put in the grandfather clause. I couldn't fit in with that; knew it was just an excuse to keep the niggers from voting, and I ain't voted since." He said that if he were able to vote, he'd support Roosevelt because he would help the "poor man and the farmer."

On the subject of political alignment, Budge noted that the Republican Party, whose first president Abraham Lincoln had emancipated the slaves from Southern states in 1863, had become a party that "stands for the rich man (G.O.P.)." Budge then asserted that "if the Democrat keeps being friendly to the poor, there soon won't be one Republican in a thousand colored people." He also believed that the North was not any better than the South in regard to racism, as in a way, white people in the North were even more alienating to African Americans in their community. Budge stated, "The only white people that is interested enough to git along with us is the ones that has lived here all their lives."

Social Context

[edit | edit source]Post-Reconstruction Voting Rights

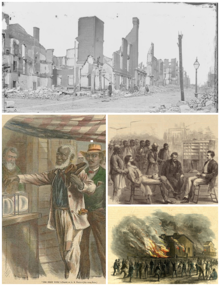

[edit | edit source]For a few years after the American Civil War, African American men were able to vote unrestricted as well as hold seats in representational congress. Reconstruction, the era directly following the Civil War, served as a brief moment of growth and freedom for African Americans. However, it was short-lived as retaliatory tension from Confederate sympathizers ultimately overcame progressivist Republican efforts to preserve civil rights for all in the South.

Ultimately, with the secret Compromise of 1877 the contested presidential election of 1876 was ceded to the Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South.[3] This effectively ended the Reconstruction Era, as federal enforcement of the fourteenth and fifteenth Amendments was weakened. More Southern Democrats ascended to power, and thus laws such as the grandfather clause, literacy tests, poll taxes, and other loophole legislation were passed to make it practically impossible for African Americans to vote. With African Americans disenfranchised, and Confederate sympathizers thus gaining a larger percentage of the voting base, these discriminatory voting laws allowed for the passing of the black codes and Jim Crow segregationist agendas throughout the first half of the twentieth century, reinforcing systemic racism.

African Americans and FDR's New Deal

[edit | edit source]Proponents of FDR's plan to pull the USA out of the Great Depression generally claim that the New Deal "marked an important step forward and had an overall positive effect on the welfare of millions of citizens of African descent."[4] Critics however argue that although New Deal legislaiton was certainly instrumental in improving the lives of a great number of Americans, it did not purposefully and effectively aim to provide equitable improvement to the lives of African Americans, and in fact that "the legislative record of the New Deal was consistently racialized and discriminatory."[5]

While programs such as the Social Security Act and National Labor Relations Act meant to bolster the financial health of Americans still in the work force, they did not cover household workers or farm workers, which were two of the main jobs available to African Americans at the time.[6] The New Deal's Homeowners' Loan Corporation and Federal Housing Administration programs had a deleterious long-term effect on systemic redlining, or the segregation of African Americans through denying access to quality housing in integrated neighborhoods.[7] Finally, while the Works Progress Administration and other federal relief programs that offered new jobs created there were about 425,000 jobs for African Americans,[8] this was just one seventh of the overall number and there was not enough federal enforcement to ensure that local organizers would not discriminate in the hiring or management processes.Thus, African American livelihood was not changed much for the better compared to during the Great Depression and the decades before[9] despite the New Deal being championed as revolutionary package of legislation.

It is, however, important to note that some New Deal programs increased awareness of the plight of the African American as well as inspired civil rights efforts.[10] The Federal Writers Project, for instance, evidently gave Black Americans an opportunity to share their stories as well as prowess in the literary arts. The Federal Art Project did the same for visual and performing arts. The legislation itself provided a blueprint for future instrumental packages of reform legislation to be ruled out.[11]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Forster, W.O. "Virgil Johnson: An Old School Colored Farmer" 1939. Federal Writers' Project Papers, folder 407. Found in UNC Online Library database: https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/03709/id/513/rec/1

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ History.com Editors. “Compromise of 1877.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, March 17, 2011. https://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/compromise-of-1877.

- ↑ “African Americans.” Living New Deal. The Living New Deal Project, August 20, 2020. https://livingnewdeal.org/what-was-the-new-deal/new-deal-inclusion/african-americans-2/.

- ↑ Brueggemann, John. "Racial Considerations and Social Policy in the 1930s: Economic Change and Political Opportunities." Social Science History 26, no. 1 (2002): 139-77. doi:10.1017/S0145553200012311.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Michney, Todd M., and LaDale Winling. “New Perspectives on New Deal Housing Policy: Explicating and Mapping HOLC Loans to African Americans.” Journal of Urban History 46, no. 1 (January 2020): 150–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144218819429.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ “Race Relations.” NCpedia. NCpedia, 2008. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/race-relations.

- ↑ Williams, Gloria Y. “African Americans and the Politics of Race During the New Deal.” Essay. In Interpreting American History The New Deal and the Great Depression, edited by Aaron D. Purcell, 131–34. The Kent State University Press, 2014.

- ↑ Ibid.