Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2021/Spring/105i/Section 24/J. Sherwood Upchurch

Overview

[edit | edit source]J. Sherwood Upchurch (1870-1950) was a politician, theatre manager, and restaurant owner from Raleigh, North Carolina. He was a City Alderman for Raleigh, North Carolina and a member of the North Carolina state legislature. Upchurch was interviewed by the Federal Writers' Project on March, 6, 1939 in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Biography

[edit | edit source]Early Life

[edit | edit source]Upchurch was born in Raleigh on October, 28, 1870, the son of Alvin and Mary Ann Upchurch. His mother died when he was five years old and his father died a few years later. Upchurch was homeless and moneyless[1]. He slept on a bed made of discarded newspapers behind the Raleigh post office[2]. He dropped out of school at eleven years old to begin working. As a child he worked a variety of jobs such as an apprentice in a machine shop and a newspaper boy at "The Chronicle." Eventually, he decided to join the circus.[3]

Entertainment

[edit | edit source]Upchurch joined the Buffalo Bill Wild West circus as a teenager in the advertising or "bill posting" department. As a member of the circus, Upchurch traveled across the country. He claimed that he visited every city in every state of the United States. Eventually, he secured the exclusive bill posting rights in the City of Raleigh which he sold to a national bill posting agency for a paid position in the company.[4]

Upchurch moved from the circus to theatre where he had the position of manager of the Academy of Music, a Raleigh theatre for stage production. As manager, Upchurch brought many plays to Raleigh and claimed "whenever there was an outstanding hit playing on Broadway, I brought the show to Raleigh, always with the original Broadway cast, regardless of cost."[5]

Political Career

[edit | edit source]Upchurch served fourteen years as a member of the City Board of Alderman in Raleigh. He also served as a City Sanitary and Health Officer for many years and multiple terms as City Auditor[6]. He lost his position in city government when Raleigh switched from a Mayoralty system to a commission system. Upchurch joked that "they changed the form of city government to get rid of me."[7]

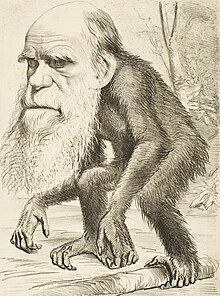

In 1925, Upchurch made his first run for the North Carolina state legislature. He ran on an anti-evolution platform with the campaign slogan "I did not come from him, neither did you! I may look like him but I refuse to claim kin, on this I stand!" His first run was unsuccessful but he made a second run in 1927 and was successful in getting elected.[8]During the 1931 session he was a member of the Financial Committee and helped pass a law requiring all automobiles owned by cities, counties and towns to be marked as such.[9]

Social Issues

[edit | edit source]Evolution Debate

[edit | edit source]

Evolution is the concept that there is a process of change in the heritable characteristics of a biological population of an organism over the course of many generations.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, evolution was a very contentious topic in the United States. It was opposed by religious leaders of the time who favored the concept of Creationism and it was also opposed by some social progressives because evolution was associated with the Eugenics movement and Scientific Racism.[10]

The evolution debate became an important wedge issue for the politics of the 1920's specifically in regards to whether evolution should be taught in schools. Evangelical leaders and Christian politicians like William Jennings Bryan traveled across the country to try to convince state legislators to ban evolution being taught in schools.[11]

In Dayton, Tennessee, a teacher named John Scopes violated an anti-evolution law by teaching evolution and was taken to court. This resulted in the widely publicized Scopes Trial. William Jennings Bryan argued for the prosecution, and famous attorney Clarence Darrow was the defense. Bryan argued that teaching evolution would undermine the Christian faith in America and replace the religion of love with "survival of the fittest." Scopes lost the trial but the debate of evolution being taught in schools continued for decades afterwards.[12]

Child Welfare in the 19th Century

[edit | edit source]

During the 19th century there was no social safety net provided by the state for poor and orphaned children. Poor and orphaned children would often have to provide for themselves. Working children were very common in the 19th century and they worked various jobs such as selling newspapers, shining shoes, and working in tight spaces in factories.[13] If child welfare was provided it came from private organizations. But these organizations did not always serve in the best interests of the children and this was especially true for racial and ethnic minorities.[14]

One New York City program would send orphaned children out to the west to work on farms, there was no vetting process and the orphans would sometimes be treated as free labor. Between 1854 and 1929 over two hundred thousand New York City orphans were sent to work on farms in rural areas.[15]

References

[edit | edit source]•Blakemore, E. (2019, January 28). 'Orphan trains' brought homeless nyc children to work on farms out west. Retrieved March 09, 2021, from https://www.history.com/news/orphan-trains-childrens-aid-society

•Chávez-García, M. (2019). Child Welfare in America. Journal of Women's History 31(4), 146-153.

•Erk, F. (1999). Scopes, Evolution and Religion. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 74(1), 51-55

•King, Robert O, (interviewer): Sherwood Upchurch in the Federal Writers' Project papers #3709, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

•Liu, J. (2020, May 30). The social and Legal dimensions of the evolution debate in the U.S. Retrieved March 09, 2021, from https://www.pewforum.org/2009/02/04/the-social-and-legal-dimensions-of-the-evolution-debate-in-the-us/

•Michael Schuman, "History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2017,

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ King, Robert O. "Sherwood Upchurch" Federal Writers' Project papers #3709

- ↑ Ibid., 7634

- ↑ Ibid., 7636.

- ↑ Ibid., 7635.

- ↑ Ibid., 7636

- ↑ Ibid., 7636.

- ↑ Ibid., 7637.

- ↑ Ibid., 7638.

- ↑ Ibid., 7639

- ↑ Liu, J. "The social and Legal dimensions of the evolution debate in the U.S"

- ↑ Erk, F. "Scopes, Evolution and Religion. The Quarterly Review of Biology,"

- ↑ Ibid., 54

- ↑ Michael Schuman, "History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working,"

- ↑ Chávez-García, M. "Child Welfare in America. Journal of Women's History"

- ↑ Blakemore, E. "'Orphan trains' brought homeless nyc children to work on farms out west"