Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2021/Spring/105i/Section 24/Chung Tai-pan

Chung Tai-pan | |

|---|---|

| Cause of death | Unknown |

| Nationality | Chinese-American |

| Occupation | Laundryman |

| Spouse(s) | Mrs. Chung (given/maiden name unknown) |

| Children | 6 |

Overview

[edit | edit source]Chung Tai-pan was a Chinese-American immigrant born in April of 1868. A Chinese nationalist, he supported the fall of the Manchus through remittances. He owned a successful laundry business in Savannah, Georgia. Chung was interviewed by Gerald Chan Sieg, a member of the Federal Writers' Project, on January 20th, 1939. [1]

Biography

[edit | edit source]Early Life

[edit | edit source]Chung was born in China in April of 1868. Chung was the youngest child of eight-- five daughters and two sons. His father ran a boy's school in Guangzhou (广州, previously known as Canton). His family also owned a rice farm in their home village. During his childhood, his mother died (date unknown), and his father remarried. According to Chung, he excelled in school. Being gifted in Chinese literary arts, he was awarded Secretary of National Chinese Convention(highly esteemed poetry award).[2] He, like many intellectuals in the Qing Dynasty, was targeted by the Manchu government for conspiracy. He fled to the United States at nineteen to escape execution and raise funds for the rebellion.[3]

Immigration

[edit | edit source]In 1887, Chung arrived in Northern California. He joined the Chinese Free Masons, a network of Chinese nationalists attempting to overthrow the Manchu government, and traveled to different cities on the West Coast for work including Los Angeles and Sacramento. His brother, who also immigrated to the United States to raise money for the revolution, offered him work in New York City. In 1890, Chung arrived in New York. Searching for more lucrative markets, he moved down South, visiting Havana, Mexico, and Tampa.[4] [5]

At 45 years old, he settled in Savannah, Georgia. Chung married a Cantonese-Spanish-American woman and had six children: Eldest son (unnamed), Chung Sang, Chung Kam, Chung Li-soon, Chung Chen, and Chung Lin-tui. In Savannah, Chung ran a farm and restaurant. He struggled to sustain the businesses. After their failure, he turned to the laundry business.[6]

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 not only barred Chinese immigrants from citizenship, but it also limited job opportunities for those already on American territory.[7] For many Chinese men, laundry was one of the few reliable industries. Chung was no exception. His laundry business boomed, and he was able to hire help outside of his family-- a staff of primarily African-American women.[8]

Later Life

[edit | edit source]After years of political turmoil, the Manchu government fell during the 1911 Revolution[9] . During the war, Chung's father and father's wife died. Soon after his brother in New York City died at the age of 86. Chung's laundry business continued to thrive. As he aged, his eldest son and second son began to manage the business. During the Great Depression, the laundry business faced economic devastation; however, the Civil Works Administration and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration provided funds to cover expenses. At 70 years old, Chung wished to return to Guangzhou before his death. He remained in Savannah so his youngest daughter, Chung Li-tui, could finish her education. He hoped that she would go to China to teach English, and that he could follow her. His death date is unknown.[10]

Social Issues

[edit | edit source]Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

[edit | edit source]Due to political unrest, famine, and little economic opportunity, many Chinese immigrated to the United States in the mid-late 19th century for work. They primarily found work in Californian gold mining and railroad building.[11] The Chinese accepted some of the lowest wages in California, beating their European counterparts for jobs. The Chinese also maintained their Chinese identity, often staying in the United States temporarily and returning to China after saving funds. Chinese immigrants in the 19th century were primarily young men. Chinatowns became known for their brothels, and White Americans started advocating for protecting "racial purity".[12]

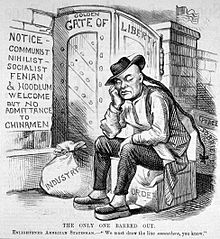

Job scarcity and racist sentiments came together in enacting the first anti-immigration policy. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned Chinese immigrants from gaining American citizenship and greatly reduced their economic opportunities.[13]

Revolution of 1911

[edit | edit source]Ranking the fifth longest Chinese dynasty, the Qing dynasty lasted over 250 years.[14] The Ming dynasty, preceding the Qing, was ruled by the Han Chinese, the majority ethnic group of China; however, the Manchus overtook the Hans in 1644.[15] Although Manchu rule was initially characterized by economic and cultural development, the latter half of the dynasty was characterized by rebellion, struggle against westernization, weakening economic situation, and natural disaster.[16]

China's markets crashed in the late 19th century. Imports were four-times the worth of their exports. Industry failed to industrialize, and heavy economic burden turned the public against the government.[17] The Qing implemented New Policies, adopting many Western models, in order to stimulate the economy. When these failed, anti-foreign sentiments were heightened.[18] The Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which turned into a genocide of Chinese Christians, was the result of increasing rejection of foreign influence.[19]

The Revolution of 1911 was driven by Sun Yat-sen. He traveled the world convincing Britain, Japan, and other foreign powers to assist his overthrow of the Manchus. He encouraged his followers to immigrate to other countries, such as the United States, to work and raise funds for the revolution[20]; today, many Chinese continue the practice of coming to the United States to raise funds to send back to their communities.[21] He succeeded in overthrowing the government in 1911, and became the first president of the Republic of China.[22]

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Laundryman, the Federal Writers' Project papers #3709.

- ↑ lbid., 3320-3323.

- ↑ lbid., 3320-3323.

- ↑ lbid., 3324-3326.

- ↑ dig

- ↑ lbid., 3324-3328.

- ↑ History.com Staff. "Chinese Exclusion Act."

- ↑ lbid., 3324-3328.

- ↑ Guo, Wang. “The ‘Revolution’ of 1911 Revisited: A Review of Contemporary Studies in China.”

- ↑ lbid., 3324-3338.

- ↑ History.com Staff. "Chinese Exclusion Act." History.com.

- ↑ Qin, Yucheng. "The Cultural Clash: Chinese Native-Place Sentiment and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882."

- ↑ History.com Staff. "Chinese Exclusion Act." History.com.

- ↑ Jiang, Fercility. "The Qing Dynasty - China's Last Dynasty."

- ↑ Guo, Wang. “The ‘Revolution’ of 1911 Revisited: A Review of Contemporary Studies in China.”

- ↑ Jiang, Fercility. "The Qing Dynasty - China's Last Dynasty."

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Guo, Wang. “The ‘Revolution’ of 1911 Revisited: A Review of Contemporary Studies in China.”

- ↑ Jiang, Fercility. "The Qing Dynasty - China's Last Dynasty."

- ↑ Guo, Wang. “The ‘Revolution’ of 1911 Revisited: A Review of Contemporary Studies in China.”

- ↑ Liang, Zai, and Qian Song. "From the Culture of Migration to the Culture of Remittances: Evidence from Immigrant-Sending Communities in China."

- ↑ Guo, Wang. “The ‘Revolution’ of 1911 Revisited: A Review of Contemporary Studies in China.”

References

[edit | edit source]- Guo, Wang. “The ‘Revolution’ of 1911 Revisited: A Review of Contemporary Studies in China.” China Information 25, no. 3 (November 2011): 257–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X11422762.

- History.com Staff. "Chinese Exclusion Act." History.com. August 24, 2018. Accessed March 09, 2021. https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/chinese-exclusion-act-1882.

- Jiang, Fercility. "The Qing Dynasty - China's Last Dynasty." Qing Dynasty History, Key Events of China's Last Dynasty. March 04, 2021. Accessed March 09, 2021. https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/china-history/the-qing-dynasty.htm.

- Laundryman, in the Federal Writers' Project papers #3709, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Liang, Zai, and Qian Song. "From the Culture of Migration to the Culture of Remittances: Evidence from Immigrant-Sending Communities in China." Chinese Sociological Review. 2018. Accessed March 09, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6816756/.

- Qin, Yucheng. "The Cultural Clash: Chinese Native-Place Sentiment and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882." The Journal of Race & Policy 8, no. 1 (Spring, 2012): 18-36. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/cultural-clash-chinese-native-place-sentiment/docview/1460173947/se-2?accountid=14244.