Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2021/Spring/105/Section 88/Pattie Debrow

Pattie Debrow | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | United States of America |

| Occupation | Farm and Domestic Worker |

| Spouse(s) | Sim

Noah Boone Spillman Debrow |

Overview

[edit | edit source]Pattie Debrow was an African American woman born to ex-slaves during the post emancipation era. She worked throughout her entire life as a field hand and a domestic worker. She married three times, had several miscarriages, and had one daughter who died young. Debrow was interviewed by Bernice Kelly Harris for the Federal Writers' Project on July 1, 1939.[1]

Biography

[edit | edit source]Early Life

[edit | edit source]Debrow was born in Merrytops, North Carolina around the time of the emancipation in 1863. Both of her parents were slaves and her mother died when Debrow was too young to remember. She was raised by her father and her Cousin Cindy, and they moved between a number of farms in search of work. She often worked alongside her father to help with finances in the absence of her mother. Between moving constantly and working as a child, Debrow did not have a stable childhood nor an education.[1]

Family Life and Marriages

[edit | edit source]Debrow married three times over the course of her life.

She married at fourteen to a man named Sim, and money was the main reason for this marriage. At fifteen, she had her first and only child with Sim, but their daughter died at the age of four due to an unknown disease. Their daughter was not able to receive medical attention, thus Debrow resorted to home remedies. After the child’s death, Sim was struck with grief and eventually grieved himself to death.[1]

Two years after Sim’s death, Debrow married Noah Boone in search for a place to settle down. During her second marriage, she was abused, experienced many miscarriages, and overworked in the fields. Debrow left Boone after he was sent to jail for theft, but after Boone’s release he came back to Debrow against her own accord. Eventually, Boone left after being driven out by the white townsmen.[1]

Debrow remained single for ten years until she decided she did not want to be alone in her old age. Her third marriage was with Spillman Debrow who already had five children. Their marriage lasted eight years but ended when conflicts arose between Ms. Debrow and Spillman Debrow’s children.[1]

Career

[edit | edit source]

Debrow learned to work at a very young age and insisted to provide for herself until her death. Her jobs consisted mostly of manual labor and domestic jobs which did not pay a lot. During the Great Depression, she received aid from the government and her neighbors, but still worked whenever she could. Debrow had contracted many injuries due to the intensity of her jobs but received no medical attention.[1]

Social Context

[edit | edit source]Inequalities in Health Care for African Americans (1860-1940)

[edit | edit source]

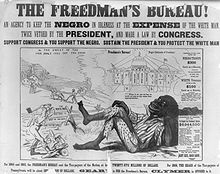

The Freedmen's Bureau was the first government agency to assist in the relocation, employment, and utilities of newly freed slaves. Under one of their responsibilities was African American health care. The Bureau assigned many doctors to become physicians for freedmen, but the Bureau had “no authority to employ physicians by contract.”[2] As such, many southern doctors refused to treat African Americans and denied them from health care.[2]

Limited access to health care for African Americans continued many years post emancipation. Between 1880 and 1910, the African American life expectancy was 25 whereas the white life expectancy was 39.[3] In a Harvard panel, one expert said, “the inequalities of the health system were built in from the beginning,” attributing the disproportionate prevalence of diseases and death among African Americans to systematic discrimination.[4]

One leading cause to the disparities in health care was due to African American underrepresentation. Around 1900, Only 2% of medical professionals were black and this percentage would remain the same until the 1980s with inaccessibility to education being the cause. African Americans were often denied medical education in a variety of methods such as creating “white-culture-based achievement tests” for a medical school or job application.[5]

African American Women and Gender Roles (1860-1940)

[edit | edit source]In post emancipation America, marriage among African American women was used for strategic reasons. A good marriage could result in economic gain, job security, and land ownership. However, marrying for economic gain has negative effects like “gender inequality” and “agricultural labor contracts.”[6] Marriage could also result in a master-slave dynamic between the husband and wife, thus repeating the actions of slave owners.

During the Great Depression, women served a vital role in securing jobs and providing for their families. Their jobs paid less than men’s labor and were limited to “nursing, teaching, and domestic work.”[7] African American women were subjugated even further to just domestic and farm work in southern states.

Black women were usually the targets of premature job termination. This is because companies prioritized white, male employees, so when the Depression hit, African American women were the first to be laid off.[8]

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Harris, interview.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pearson, "There Are Many Sick..."

- ↑ Ewbank, "History of Black Mortality and Health before 1940."

- ↑ Milano, "How Slavery Still Shadows Health Care."

- ↑ Byrd and Clayton, "Race Medicine and Health Care in the United States: A Historical Survey."

- ↑ Bloome and Muller, "Tenancy and African American Marriage in the Postbellum South."

- ↑ "Great Depression History."

- ↑ Rotondi, "Underpaid, But Employed: How the Great Depression Affected Working Women."

References

[edit | edit source]- Bloome, Deirdre and Christopher Muller. “Tenancy and African American Marriage in the Postbellum South.” Demography 52, no. 5 (2015): 1409–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0414-1.

- Byrd, Michael and Linda Clayton, “Race, Medicine, and Health Care in the United States: A Historical Survey,” Journal of the National Medical Association 93, no. 3 (2001): 195. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.1.75

- Ewbank, Douglas C. “History of Black Mortality and Health before 1940.” The Milbank Quarterly 65 (1987): 100. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349953.

- “Great Depression History.” History.com. A&E Television Networks. Last modified October 29, 2009. Accessed April 7, 2021.

- Harris, Bernice K. July 1, 1939. “I’d Like to Have A Coca Cola.” Interview. From the Federal Writers Project papers #3709, Folder 451, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Milano, Brett. “How Slavery Still Shadows Health Care.” The Harvard Gazette. Harvard Gazette. Last modified October 29, 2019.

- Pearson, Reggie L. “There Are Many Sick, Feeble, and Suffering Freedmen’: The Freedmen's Bureau's Health-Care Activities during Reconstruction in North Carolina, 1865-1868.” The North Carolina Historical Review 79, no. 2 (2002): 141–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23522765.

- Rotondi, Jessica Pearce. “Underpaid, But Employed: How the Great Depression Affected Working Women.” History.com. A&E Television Networks. Last modified March 11, 2019. Accessed April 7, 2021.