Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2020/Fall/105/Section071/Geo Burris

Geo Burris | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1905 |

| Died | Unknown |

| Occupation | Sharecropper, Service Worker |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Burris |

Overview

[edit | edit source]Geo Burris was an African-American former sharecropper during the Great Depression. He was interviewed by Mary Pearl Brown in August, 1939 for the Federal Writers Project. He was only 34 years old at the time. [1]

Biography

[edit | edit source]

Burris, born in South Carolina in 1905, grew up with seven sisters on a sharecropping farm. Raised in an African American household, his family struggled with financial stability which led to constant relocation as the family couldn’t afford to stay in one place for long. Through Burris's early adulthood years, he used the small amount of money he had saved up to buy moonshine and had an affair with a woman named Jane who he would later get pregnant. Due to his affair with Jane and her being pregnant with his child, Burris would soon be forced to marry her as her father threatened his life. After his marriage to Jane, his wife soon went into labour. Here she would suffer from a complicated birth in which she and her unborn child would both pass away. Shortly after, Burris's mother became extremely ill and also passed away. Unable to pay to afford a funeral, Burris and his siblings fell into debt and moved to York County, South Carolina. A few months passed and the family struggled to make ends meet, falling into an even larger debt. Due to an increasing debt, the remaining family moved to Charlotte, North Carolina where Burris began working in a boarding house which paid him a mere three dollars per hour. Shortly after, Burris's father passed away and left his children to mend life on their own in a new city. Due to racial unrest, Burris continued to work at the boarding house where he was paid poorly and worked in terrible conditions. Just one year before this interview took place, Burris was arrested and spent ten days in prison for possession of an illegal firearm that he was given to him by a stranger. Upon his release, he continued to live the way he previously did, and attempted to provide for his sisters. He also looked after his nephew, George Washington, as many of his sisters became single mothers and struggled to take care of their children. Burris's last statement to be recorded was, “From now on, I’m looking after Geo”. [3]

Social Issues

[edit | edit source]Sharecropping Industry for African American Individuals

[edit | edit source]

After the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves in the southern states. Due to this, many African American families ended up in sharecropping or became tenant farmers. The idea of sharecropping involved African American families living on the farm while paying the landowner in the form of crops. The landowner was more than likely a white man who previously owned slaves before the Civil War. Due to the constant payment in the form of crops, these sharecropping families oftentimes fell into increasing debts that would prevent them from living alone in the future and purchasing their own farms. [5]Oftentimes the African American families ended up in disputes with the landowner and moved from location to location as they were not able to understand the contract due to a lack of education from the Jim Crow Laws. Tenant Farmers essentially followed the same idea as sharecroppers, however, they would pay their rent in the form of money and not in the form of crops like the sharecroppers did.[6] Many tenant farmers would move from farm to another as they were treated in poor conditions. This led to a form of racial blacklisting in which farmers who moved from one farm to another were placed on a list. This list would be shared with landowners who would then see the farmers as unreliable and refuse to hire them as they continuously shifted. Due to this, sharecroppers and tenant farmers would attempt to form connections with each other so they could gain a greater representation in their communities and disassemble the hegemonic forces of white individuals in the south.

African American Racial Issues in the WorkForce

[edit | edit source]

African American struggled to find work in the South after the Civil War took place as they were still treated extremely poorly. They usually worked jobs in service to avoid the betrayal and poor treatment they received on farms.[8] Even though these jobs were seen as an upgrade from farm life, they were filled with discrimination. There was discrimination in pay, labor, and sometimes no pay at all. [9] Even with all of these conditions, African Americans had to work. According to law, if a black individual were to reside in the south, they must work or it would be seen as a “vagrancy” crime and they could end up in jail. Later on, these black codes would be replaced with the Jim Crow Laws in 1877 which was a new set of laws which followed the same ideas.[10] The Jim Crow Laws maintained segregation in the south. This allowed for the separation of color in service. The Jim Crow laws were defined by the famous phrase, “separate but equal”.[11] In the 1930’s when the Great Depression occurred, the NAACP would make sure that African Americans were accounted for in the New Deal even with the Jim Crow Laws still in place. [12] The New Deal created sources that helped service workers, however, African American individuals were oftentimes left out of it. Black families were also unable to benefit from the Social Security Act and Worker’s Unions due to discrimination and segregation under the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. African Americans during the Great Depression faced angry white supremacists. In the nation's large cities, protesters commonly shouted "niggers, go back to the cotton fields. [13] Furthermore, in the Great Depression of the 1930s many of the nation's recovery programs that were devised to boost the nation's economy, discriminated against blacks in both hiring and wage levels. [14]

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Federal Writers Project Papers". dc.lib.unc.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ File:Sharecropper on Sunday, Little Rock, Ark., October 1935. (3110588422).jpg

- ↑ "Folder 303: Brown, Mary Pearl (interviewer): Untitled :: Federal Writers Project Papers". dc.lib.unc.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

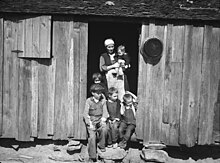

- ↑ File:Farm Security Administration sharecropper photo of Mrs. Handley and some of her children in Walker County, Alabama. - NARA - 195926.tif

- ↑ King, Katrina Quisumbing; Wood, Spencer D.; Gilbert, Jess; Sinkewicz, Marilyn (2018). "Black Agrarianism: The Significance of African American Landownership in the Rural South". Rural Sociology 83 (3): 677–699. doi:10.1111/ruso.12208. ISSN 1549-0831. https://www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ruso.12208.

- ↑ McInnis, Jarvis C. (2019-09-01). "A Corporate Plantation Reading Public: Labor, Literacy, and Diaspora in the Global Black South". American Literature 91 (3): 523–555. doi:10.1215/00029831-7722116. ISSN 0002-9831. https://read.dukeupress.edu/american-literature/article-abstract/91/3/523/139947/A-Corporate-Plantation-Reading-Public-Labor.

- ↑ File:We want white tenants.jpg

- ↑ "Great Migration - HISTORY". www.history.com. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "Federal Writers Project Papers". dc.lib.unc.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "black code | Laws, History, & Examples". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "Jim Crow laws". Wikipedia. 2020-10-21. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jim_Crow_laws&oldid=984733838.

- ↑ Hamilton, Dona Cooper (1994-12-01). "The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and New Deal Reform Legislation: A Dual Agenda". Social Service Review 68 (4): 488–502. doi:10.1086/604080. ISSN 0037-7961. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/604080.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow . Jim Crow Stories . The Great Depression | PBS". www.thirteen.org. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow . Jim Crow Stories . The Great Depression | PBS". www.thirteen.org. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

References

[edit | edit source]- The Southern Historical Collection at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collection Library. The Southern Historical Collection at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collection Library. UNC Universities Libraries. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/search/collection/03709/searchterm/folder_303!03709/field/contri!escri/mode/exact!exact/conn/and!and/order/relatid/ad/asc/cosuppress/0.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Black Code.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., August 20, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-code.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. “Jim Crow Law.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., August 21, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/Jim-Crow-law.

- “Recollections of the Great Depression ‘No Jobs for Niggers Until Every White Man Has a Job.’” 2008. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education62 (1077–3711): 29. http://bsc.chadwyck.com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/search/displayIibpCitation.do?SearchEngine=Opentext&area=iibp&id=00368604.

- Stewart, Gary. 1998. “Black Codes and Broken Windows: The Legacy of Racial Hegemony in Anti-Gang Civil Injunctions.” The Yale Law Journal 107 (7): 2249–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/797421.

- Exum, Jelani Jefferson. 2012. “The Influence of Past Racism on Criminal Injustice: A Review of The New Jim Crow and The Condemnation of Blackness.” American Studies 52 (1): 143–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/ams.2012.0028.

- King, Katrina Quisumbing, Spencer D. Wood, Jess Gilbert, and Marilyn Sinkewicz. “Black Agrarianism: The Significance of African American Landownership in the Rural South.” Rural Sociology 83, no. 3 (2018): 677–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12208.

- Mcinnis, Jarvis C. “A Corporate Plantation Reading Public: Labor, Literacy, and Diaspora in the Global Black South.” American Literature 91, no. 3 (September 1, 2019): 523–55. https://doi.org/10.1215/00029831-7722116.