Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2015/Fall/Section 020/A Shrimp Fisherman

Unknown (French Origin) | |

|---|---|

| Born | New Orleans, Illinois |

| Died | Unknown Unknown |

| Occupation | Shrimp Fisherman, Incinerator Worker |

| Spouse(s) | Althea |

Overview

[edit | edit source]Name unknown, the shrimp fisherman was born on Josephine Street and Rousseau Street in New Orleans, Louisiana sometime between 1903 and 1907. He worked various manual labor jobs on the river to support his family and was involved in the Maritime Union. He was the subject of an interview for the Federal Writers' Project.

Biography

[edit | edit source]Early Life

[edit | edit source]The shrimp fisherman was born into a family of 12 but many of his siblings died in childhood. His father used to work as a longshoreman and was a drunkard who spent all the money he made on liquor. The father neglected his family and was repeatedly jailed for his behavior. His drunken behavior continued on after the death of his wife. The Shrimp Fisherman’s mother died on February 25, 1926 due to bleeding several days after having her unborn baby.

The shrimp fisherman attended Saint Michael’s School but quit in the 7th grade to look for manual labor out on the river.

Adulthood

[edit | edit source]He was employed on a boat but resigned after having problems with the skipper. Once he began working on the river, he joined the National Maritime Union.

The shrimp fisherman then moved to Annunciation Street in New Orleans and accepted a job fishing shrimp and catfish to sell off the dock. He also worked a night job at the incinerator, making four dollars a night.

He travelled to places like China, Germany, England, France, and Brazil for work but also sought entertainment, paying the women of those countries for prostitution. While traveling, he met Lulu Johnson who was an infertile Egyptian woman he wanted to marry. However, he left her after finding out she had a husband.

After leaving Johnson, he married a woman named Althea. The couple had been married for nine years at the time of the interview for the Federal Writers' Project. Althea was infertile so the couple never had children. Instead, they adopted the shrimp fisherman’s 15-year-old sister.

The shrimp fisherman gave his wife many responsibilities. Though Althea did not work, she managed the family’s finances and the Shrimp Fisherman left all his wages in her hands.

Death

[edit | edit source]The shrimp fisherman’s death date and location are unknown [1].

Social Issues

[edit | edit source]Rise of Maritime Unions

[edit | edit source]

Maritime workers have a long history of struggling to improve their work conditions, establishing many unions to that end. Most often the industry has been organized by craft. However, there have been attempts to unite all maritime workers in large organizations.

The idea of maritime unions first arose in the nineteenth century with sailors and seamen. People of both occupations endured dangerous working environments, were scammed often, and were hustled and taken advantage of on shore. Rule on ships was harsh as well. Captains could order corporal punishment until the 1890s. Seamen finally gained the ability to unionize legally in the 1930s with the New Deal reforms [2].

Early unions were short-lived until the late 19th century because the nature of maritime work hindered organization. Sailors constantly moved to foreign cities, changing crews and hardly keeping local ties. Maritime workers also wasted much of their money drinking liquor [3].

Sailors founded the Sailors Union of the Pacific in 1886 from a strike over wages, working conditions, and union representation. Other seafaring workers formed organization at this time. Some of these organizations included the Marine Firemen, Oilers and Watertenders Unions (MFOW), the Marine Engineer’s Beneficial Association (MEBA), the Inlandboatmen’s Union (IBU), the Union of Masters, and the Internatinoal Seaman’s Union (ISU) [4].

According to the Industrial and Labor Relations, “The ISU groups flourished during World War I but dwindled after the disastrous shipping strike of 1921.” [5] Racial divisions and rivalry among unions marked the low point for maritime unions. During this time, strike workers saw their wages reduced by 25 percent. Mariners did not recover from government repression until the 1930s after a strike of 99 days duration [6].

Recently the Seafarers International Union (SIU) has succeeded in unifying more of the industry. Presently, the SIU has an estimated 20,000 members and a dozen affiliate unions [7].

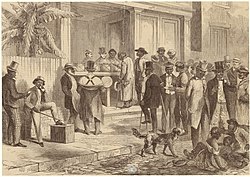

African American Work in New Orleans

[edit | edit source]

The African Americans in New Orleans quickly adapted to the responsibility of free labor after the abolition of slavery. However, racial discrimination caused many economic failures. African Americans were often prohibited from receiving loans and kept away from jobs. The limited number of jobs became more competitive with the rapid population increase of African Americans in New Orleans [8].

Reconstruction brought more problems for the African American worker. The expensive living cost in New Orleans and the high unemployment rate made it difficult for workers to rise above the subsistence level. Only four percent of all unskilled laborers in 1870 held at least $200 in property [9].

In spite of discrimination, African Americans were able to share a portion of skilled jobs. While they made up only 25 percent of the total labor force, they held between 30 and 65 percent of all jobs as steamboat men, draymen, masons, bakers, carpenters, cigar makers, plasterers, barbers, and gardeners in 1870. It was this occupational base that served African Americans well into the twentieth century [10]. Until 1930, African Americans held a disproportionately high percentage of all jobs as boatmen, draymen, shoemakers, carpenters, coopers, masons, plasterers, and tobacco workers [11].

The Great Depression hurt African Americans economically as well. Black institutions were financially unstable and often passed to white ownership. Fortunately, the Works Progress Administration provided educational programs and job opportunities for African Americans during the difficult economic years. Individuals were able to own various businesses and work on the New Orleans riverfront [12].

Constant racial discrimination led African Americans to become involved in various labor unions like the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). African Americans were often excluded by “Jim Crow unionism” in order to maintain segregated locals. With the split of the AFL and the CIO, many African Americans left with the CIO to seek a greater chance equal opportunity with their white counterparts. However, African American inclusion was only seriously considered when union numbers demanded it. It was not until the late 1960s when the AFL-CIO endorsed the civil rights agenda to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 [13].

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ “A Shrimp Fisherman.” Federal Writers’ Project. University of North Carolina Southern History Collection. Print. p. 1-15.

- ↑ Reagan, Michael. “Maritime Workers and Their Unions.” Waterfront Workers History Project. Accessed October 16, 2015. https://depts.washington.edu/dock/maritime_intro.shtml.

- ↑ Record, Jane Cassels. The Rise and Fall of a Maritime Union. New York: Sage Publications, 1956. p. 81.

- ↑ Reagan, Michael. “Maritime Workers and Their Unions.” Waterfront Workers History Project. Accessed October 16, 2015. https://depts.washington.edu/dock/maritime_intro.shtml.

- ↑ Record, Jane Cassels. The Rise and Fall of a Maritime Union. New York: Sage Publications, 1956. p. 82.

- ↑ Nelson, Bruce. Workers on the Waterfront: Seaman, Longshoremen, and Unionism in the 1930s. Illinois: Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois, 1988.

- ↑ Reagan, Michael. “Maritime Workers and Their Unions.” Waterfront Workers History Project. Accessed October 16, 2015. https://depts.washington.edu/dock/maritime_intro.shtml.

- ↑ “African Americans in New Orleans: Making a Living.” New Orleans Public Library. Accessed October 17, 2015. http://www.neworleanspubliclibrary.org/~nopl/exhibits/black96.htm.

- ↑ 1. Blassingame, John W. Black New Orleans, 1860-1880. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Accessed October 19, 2015. ProQuest ebrary. p. 63.

- ↑ “African Americans in New Orleans: Making a Living.” New Orleans Public Library. Accessed October 17, 2015. http://www.neworleanspubliclibrary.org/~nopl/exhibits/black96.htm.

- ↑ Blassingame, John W. Black New Orleans, 1860-1880. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Accessed October 19, 2015. ProQuest ebrary. p. 63.

- ↑ “African Americans in New Orleans: Making a Living.” New Orleans Public Library. Accessed October 17, 2015. http://www.neworleanspubliclibrary.org/~nopl/exhibits/black96.htm.

- ↑ Reich, Steven. Great Black Migration, The: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic. Westport: ABC-CLIO, 2014. pp. 1-7, 84-88.