Editing Internet Texts/Women in Hemingway's fiction/Catherine Barkley

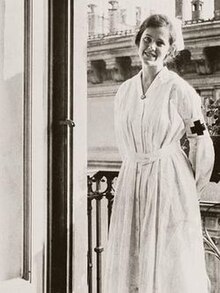

Catherine Barkley is the heroine of A Farewell to Arms, a novel published in 1929 which explores both the theme of war and the theme of love. The action is set in Italy and Switzerland during the First World War and its protagonist, Lieutenant Frederick Henry gradually falls in love with a Red Cross nurse, Catherine. She, indeed, seems loveable, at least according to Hemingway’s alleged standards. Seen as both beautiful and obedient, she is claimed to have two of the most vital characteristics which make the “saintly” woman or the “goddess”, Hemingway’s embodiment of the ideal.

The portrayal of Catherine was inspired by Agnes von Kurowsky, Hemingway’s first and unfulfilled love. Whereas in reality it was not “a fully realized love affair”, writing fiction enabled Hemingway to improve the real story and fantasise about his unsuccessful relationship with Agnes.[1] Writing the novel could have served as a means of dealing with his unfulfilled desires and wounded pride after having been rejected by creating a character which was the embodiment of his dreams. Being an idealised version of a real person, Catherine is generally perceived as unrealistic and unconvincing. Many critics reviled the character for being one-dimensional or even went as far as to accuse Hemingway of his inability to present Catherine as a flesh and blood person. Relying on the author’s biography may have been one of the reasons of such a negative perception of the character. Since Hemingway was believed to be antagonistic towards women, it should be in no way surprising that the fictional females he created are either “submissive infra-Anglo-Saxon women that make his heroes such perfect mistresses” or “bitches of the most soul-destroying sort”.[2]

Such a categorisation proposed by Edmund Wilson was adopted by other critics and prevented them from recognising the true nature of Catherine. While analysing Hemingway’s fiction, however, his style must be taken into consideration. It is possible that Catherine’s submissiveness and passivity is only the tip of the iceberg. Once her comments are read as ironic, her self-awareness becomes evident.

This side of Catherine was not overlooked by Young, according to whom “Catherine Barkley has at least some character in her own right, and is both the first true ‘Hemingway heroine,’ and the most convincing one.”[3] According to Baker, “the meaning of [the characters’] lives must be sought in the kind of actions in which they are involved.”[4]

Physical attractiveness is, obviously, the very thing that draws Henry to Catherine. At their first meeting he observes: “Miss Barkley was quite tall. She wore what seemed to me to be a nurse’s uniform, was blonde and had a tawny skin and gray eyes. I thought she was very beautiful”. [5] Although it may seem natural that her appearance is what Henry notices first, later in the novel Catherine’s beauty is stated a number of times which may suggest Henry’s superficiality. Since he repeatedly praises Catherine for her beauty, one could believe that had it not been for her looks, he would not have fallen in love with her. Hemingway’s creation of the character seems to show that it is not personality, but appearance which is women’s strength. After all, Henry did not have any intentions of getting involved into a serious relationship; what he wanted was to satisfy his needs, which is implied in the question he asks Catherine: “Isn’t there anywhere we can go?”.[6] Later, he thinks:

This was better than going every evening to the house for officers where the girls climbed all over you and put your cap on backward as a sign of affection between their trips upstairs with brother officers. I knew I did not love Catherine Barkley nor had any idea of loving her.[7]

He thus admits that Catherine may serve as a substitute for a prostitute. She, certainly, does not have loose morals, but it does not preclude Henry from thinking that their relationship may be purely sexual.

This, however, is Henry’s perception of Catherine. Henry tells the narrative of the novel from his own point of view which means that readers see Catherine through Henry’s eyes. At the beginning, he perceives their relationship as a sexual conquest. Later, he continues to idealise it viewing himself as the one in control and Catherine as a beautiful woman willing to fulfil his wishes and expecting nothing in return. What Henry fails to realise is that Catherine’s nurturing gives her an advantage and allows her to influence Henry’s perception of the war and the world.[8]

She is perfectly aware of the fact that Henry is playing a game and what he says is a lie. It is thus not enough to say that Catherine recognises the game Henry is playing, but she also voluntarily enters it. “This is a rotten game we play, isn’t it?”, she asks and then adds, “You don’t have to pretend you love me. (…) I had a very fine little show and I’m all right now. You see I’m not mad and I’m not gone off. It’s only a little sometimes”. [9] Henry, preoccupied with his sexual conquest, fails to recognise that Catherine’s involvement in his “game” is not a sign of her submissiveness, but rather her way of recuperating and surviving in the time of war. Catherine, in fact, uses him for her own purposes. As the action progresses, the relationship proves to be therapeutic for her. The development of their affair parallels her recovery from depression.

Catherine’s traumatic past is, therefore, one of the reasons why she is willing to enter a relationship with Henry, even if it is not based on love. The horrific present is another reason. The novel is set in the time of the First World War, the time when people were clinging to anything that could keep them sane and distract their thoughts from the atrocities of war. More often than not they sought solace in love. Regardless of its genuineness, it was preferable to grief, fear or pain and offered an escape from the reality. Catherine’s desire to forget about her loss may thus account for the foolish dialogues and her seeming naivety displayed in her questions about love.

As Nolan writes, “her earlier romantic attitude toward war and life has (…) been shattered.”[10] The death of her fiancé made Catherine realise what war truly was, contrary to her previous romantic ideas. The trauma Catherine suffered from revolutionised her life and her world view and contributed to her break with traditionalism. Just as the members of the Lost Generation, she is disillusioned with the post-war reality and rejects moral values she once held dear. The war made a modern woman out of her, a woman who often displays an ironic view on the world.

In comparison to Catherine Henry, indeed, appears to be very conservative by holding on to the traditional value system. After all, it is Henry who thinks marriage is necessary once he finds out about Catherine’s pregnancy. She, on the other hand, does not wish to be restricted by social norms. As a modern woman, she is frustrated with conventional gender roles. She also confesses to Henry that she does not believe in God: “I haven’t any religion. (…) You’re my religion. You’re all I’ve got”.[11] These statements, often read as a sign of Catherine’s submissiveness, actually show that she sees herself as a liberated woman who sets her own rules regardless of society’s expectations.

In his article “Performing the Feminine” Traber writes, “Catherine should be read as a woman with agency, someone attempting to find meaning and achieve a sense of psychological equilibrium against the background of war.” He argues that Catherine, in fact, “performs” her identity. Being aware of the expectations and stereotypes concerning her gender, she manipulates them and consciously plays a role of a proper woman. What informs the readers of her true nature is “her repeatedly calling attention to her role-playing” and her cynicism which is already visible in the first scene with Catherine when Henry states, “There isn’t always an explanation for everything”, and she answers, “Oh, isn’t there? I was brought up to think there was”.[12]. Later in the novel Catherine says, “I’ll do what you want and say what you want and then I’ll be a great success, won’t I?”.[13] After asking Frederick about women he has been with, Catherine says she will do anything to please him, which would liken her to a prostitute. Nonetheless, once it is assumed that she is only “performing the feminine”, her statement must not be taken literally. What it indicates is her “ability to read male desire and treat sexuality as just another game”, an ability which helps her survive in the world.[14] Her submissiveness and insipidity is thus only a mask and in order to understand Catherine’s character, the irony in her dialogues and behaviour cannot be overlooked. Not until these aspects of her character are taken into consideration, does Catherine emerge as a self-aware and powerful woman who, in fact, seems to control Henry contrary to what he may believe.

Not only is Catherine unwilling to submit, but she actually competes with Henry. Her wish to look like Henry and her suggestion that she cut her hair and he grows his shows her desire to be equal. She wants to “blur their separate identities” and gender boundaries which threatens Henry who wishes to maintain the hierarchical structure of their relationship. He “feels a sense of loss at the disappearance of a more stable and traditional source of masculine identity in war” because of the shift in gender roles. According to Hatten, desire is the basis for their relationship, the way in which Henry endeavours to affirm his manhood. However, by giving women, in the example of Catherine, the access to desire as well, Hemingway undermines masculinity and makes women more powerful.[15]

As it has been presented, Catherine may easily be viewed in a stereotypical and sexist way as a passive, obedient woman willing to serve her lover. However, once Hemingway’s style and Catherine’s ironic attitude are assumed, she emerges as a multi-faceted character. By labelling her as a “saintly” woman, her strength, courage and self-awareness are overlooked. Instead, she should be perceived as a modern, confident woman who is not willing to be confined by the norms and expectations of society. Disillusioned with the reality and traditional ideals, she seizes her liberty by becoming involved in a relationship with Frederick as a means of recuperating from her trauma and surviving in the war-ravaged world.

Quiz

[edit | edit source]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Kert, Bernice. 1983. The Hemingway Women. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ Wilson, Edmund. 1939. “Hemingway: Gauge of Morale”, in: Harold Bloom (ed.), 2005. Ernest Hemingway. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 7-23.

- ↑ Young, Philip. 1966. Ernest Hemingway: A Reconsideration. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- ↑ Baker, Carlos. 1956. Hemingway, the Writer as Artist. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. [1929] 1957. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. [1929] 1957. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. [1929] 1957. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ↑ Gizzo, Suzanne del. 2003. “Catherine Barkley: Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms”, in: Jerilyn Fisher and Ellen S. Silber (eds.), Women in Literature: Read-ing Through the Lens of Gender. Westport: Greenwood Press, 105-107.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. [1929] 1957. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ↑ Nolan, Charles J. 2009. “‘A Little Crazy’: Psychiatric Diagnoses of Three Hemingway Women Characters”, The Hemingway Review 28, 2: 105-120.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. [1929] 1957. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. [1929] 1957. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest. [1929] 1957. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ↑ Traber, Daniel S. 2005. “Performing the Feminine in A Farewell to Arms”, The Hem-ingway Review 24, 2: 28-40.

- ↑ Hatten, Charles. 1993. “The Crisis of Masculinity, Reified Desire, and Catherine Bar-kley in A Farewell to Arms”, Journal of the History of Sexuality 4, 1: 76-98.