Editing Internet Texts/Introduction to audio description

This project is devoted to the subject of audio description. Its aim is to provide basic information concerning audio description, including its definition, purpose, types and guidelines. The main focus of the practical considerations in the project concern the audio description of paintings as possibly the easiest type of audio description. Other types of audio description (in theatre productions and movies) is to be developed, possibly as separate subpages. Users of wikiversity are welcome to help develop the project further. This page may be used as a starting point for persons interested in audio description. The project requires no professional prior knowledge from the readers. Apart from theoretical background, practical elements also feature in this project, including two assignments for the readers.

What is audio description

[edit | edit source]Audio description, also called verbal description, video description or descriptive narration, is a supplementary narration or commentary to television and theatre productions as well as other forms of visual art, which aims to provide the blind or visually impaired persons with a description of the key visual elements in order to facilitate their comprehension as well as enable to experience more fully a story or a particular piece of art. [1]

History

[edit | edit source]Audio description has existed in various forms for a long time but its formal and conceptual basis was developed in the 1980s in the United States. The starting point is said to have been the work of Gregory Frazier at San Francisco State University in 1974 and his Master's Thesis, in which he developed foundations of the process of audio description. Following that, in the 1980s, Margaret Pfanstiehl, who founded the Metropolitan Washington Ear oferring reading service for the blind, along with her husband Cody began to cooperate with theatres, museums and the TV in order to supply the blind and visually impaired with an audio description provided via a sound enhancing transmitter. In the mid 1980s audio description reached Europe as a theatre in Averham, Nottinghamshire is said to have provided a first audio descripted live performance. [2]

Types of audio description

[edit | edit source]

There are different types of audio description, depending on the medium to which they are attached and each of them requires a different approach. Audio description of visual arts such us paintings or sculptures is provided in many museums by means of recorded audio tours available for instance on audio players which can be bought or rented, special cell phones (Guide by Cell and On Cell) and applications.[3] By extension it is prepared earlier on and provided to the listeners in a ready-made form.

By contrast, in movies and theatre production descriptive narration appears during breaks between dialogues which imposes additional time constraints on the person providing audio description. In theatres the commentary is provided during the breaks between the dialogues of the performance. The describer, sitting in a special booth, describes what is happening on the stage,which the viewer listens to via equipment provided by the theatre.[4] The description concerns not only the action necessary to understand the story but also the setting, style, costumes, scenery and design of the production as well as facial expressions of the characters, visual jokes and any text displayed.

Audio description in theatre, TV and cinema differs from the audio description of paintings and sculptures in that the former contains a sound layer which enables the visually impaired to partially participate in the performanes despite their inability to see the visuals.In the case of paintings and sculptures the listeners have no access to the works described and need to fully rely on the image which the audio describer provides them with through their descriptions.

The difference between audio description in movies and theatre on the other hand lies in the fact that while audio description in movies is usually prerecorded, imposed on and timed with the soundtrack, theatre performances require more spontaneity as each of them is staged live. As a consequence the audio describer needs to be prepared for any changes in the timing and adjust his or her description accordingly, as not to interfere with the voices of the actors.[5]

Matters of difficulty in audio description

[edit | edit source]There are a number of difficulties in audio description. Many of them are connected to the great responsibility that lies on the person doing the work. Especially in paintings and sculptures (purely visual works of art) the audio describer is solely resposible for creating the image that the visually-impaired person cannot see. Although language is not the only tool employed (as in some cases it is possible to rely on other senses in experiencing a work of art, as in sculptures), it is extremely important to use it in such a way that the blind can get as close to the experience of a sighted person as possible.

Objectivity versus interpretation

[edit | edit source]As has been mentioned above, the audio describer creates an image for the visually impaired person. They should remain objective and describe only what the sighted person would normally see, without adding information or imposing their own interpretation. At the same time, however, the audio describers should strive to allow the visually impaired the most full impression and experience of a work of art, which may not be possible without some interpretating on their part. A good example of that are some of the techniques used in audio description in order to enhance that experience, such as the use of comparisons. Seeing correlation between two images is a matter of personal preference and experience, but it may bring the visually impaired person closer to intention or idea behind a particular work of art.

Andrew Holland provides an example of that when comparing two descriptions, one of which he considers „purely objective” and the other, more elaborate and featuring comparisons:

At top and bottom are areas of white frosty, silvery white scratched and rubbed in places to create an uneven surface like snow drifting across dirty ice[5]

Target audience of audio description

[edit | edit source]It is important to remember that the target audience of audio description can be varied, as there are different levels of visual impairment. A person who lost sight in adulthood may remember particular colors and have some visual memory of the world, while persons who were born blind have no such recollection, although it is said that they may base their interpretation of them on cultural associations. [6] According to the The Audio Description Project website (organized by the American Council of the Blind), most listeners belong to the former category and many of them have only partially lost their sight and thus may still recognize colors, shades or have limited vision.[7]

Time constraints

[edit | edit source]Time constraints apply to all types of audio description although they come for different reasons. In theatre, cinema and TV the time available is the duration of the break between dialogues. The audio describer needs to choose among a great number of details that make up a scene. Many things may be happening at once and the audio describer need to make a decision as to what she or he is going to draw the listeners' attention, what is the most important and what cannot be deduced from the dialogue. [5] This in turn means that some details will necessarily be omitted from the description which consequently will affect the reception of the production.

When it comes to describing paintings and sculptures, the time is limited by the listener's attention span. Different approach is needed depending on the audience and the form of the audio description. In the case of audio description provided in museums, where stops in traditional tours last around 90 seconds, the audio description of a work of art lasts a few minutes at most. When it comes to virtual tours, when fatigue of a traditional tour is not a factor and the listeners can go back to the recorder material at any point, the stops can be longer.

Guidelines for audio description of paintings

[edit | edit source]Structure and elements

[edit | edit source]Before you begin constructing your audio description, gather as much information as possible about the author of the work you describe, his style, technique, the history of the painting, interpretation and critique. The more you know about the work of art, the more complete picture you can present to your listeners. In addition, by finding out about a certain school of painting, technique or styles you will learn the needed vocabulary and will be able to formulate your ideas more clearly and precisely.

Once you have done your research and collected all the needed information, you can proceed to create your audio description. Below are given some considerations on what an audio description should contain based on the guide laid out by Lou Giansante [3] :

- Introducing the work: give the basic information - what is the title of the work, date of creation, author, location and dimensions Example: Early Sunday Morning. Painted in 1930 by Edward Hopper. It’s an oil painting on canvas. The dimensions are 35 inches high by 60 inches wide.

- Summary: provide the listener with a summary of the subject (content) and style of the painting.

Example:

This painting, as tall as an average person and as wide as a seven foot couch,

fills an entire wall in its massive one foot wide frame.

It is a dynamic woodland scene of a hunter in full stride

tearing himself away from the last embraces of his beloved

as his dogs impatiently sniff the air and strain at their leashes,

while Cupid slumbers on a hillside in the background.

Their figures dominate the expanse of the painting.

[8]

Venus and Adonis by Titian - Point of view: establish the point of view from which you are describing the painting: whether it is the perspective of the painting or the painter; make sure to underline it also when using phrases like "to the right" as they are relative and depend on the perspective.

Example:

- Use and refer to the listener's experience: compare what is seen on the painting with real-life objects, measure objects referring to the human body (for example, in measuring height). You may also guide the listener to use his own body in order for him or her to understand for instance the position of the person in the picture.

Example:

-

Technique: include information concerning the technique used in a painting, refer to the school of painting the artist represents and describe briefly how a particular style is supposed to affect the viewer.

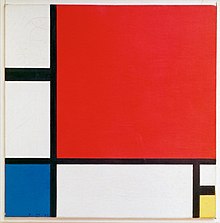

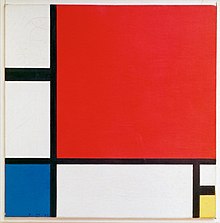

Example:

Composition is a good example of Mondrian's ideas about what makes a good painting. First of all, he maintained that art should not concern itself with reproducing images of real objects in the world. He thought art should express only the universal absolutes that underlie reality. So he rejected all sensuous qualities like texture, and the illusion of depth, and a wide palette of colors. Besides black and white, he used only the primary colors-red, blue, and yellow. These three are called primary because they are pure colors and you can make any other color my mixing them. And his compositions are composed of flat areas of colors in the geometric shapes of squares and rectangles. There are only right angles and straight lines in his paintings. No curves or any other shapes.[8]

Composition No. II, with red, blue, yellow and black by Piet Mondrian

Language

[edit | edit source]One of the most important things to remember when writing audio description is that you are producing a text meant not to be read but listened to. In addition, quite often the listeners will be able to hear it only once, which means that the syntax should not be too complex. It is easier for the receivers if important information is given in simple sentences rather than complex ones. Subordinate clauses which split the main clause are particularly difficult because they require the reader to keep in mind the first half of the sentence while receiving the information contained in the dependent clause. [3]

For similar reasons, it is recommended to use active instead of passive voice. In the latter, the subject of the sentence may not be easily identifiable if heard only once, which may cause the listener to lose time trying to dicipher the meaning instead of focusing on what is coming next. Depending on the audience, you may want to explain certain terms by inweaving their definitions in the following sentence. In general, you should not avoid using terms from history and art. It gives your listeners context and may help them "see" and understand the painting or sculpture better. Finally, avoid using impersonal pronouns like "one" or "one's" and replace them by "you" and "yours". This way you close the distance between the listener, yourself and the work of art. [3]

Consider the needs of your audience and adjust your language accordingly. Depending on the type of listeners to whom you direct your description, use jargon and specialized vocabulary sparingly (unless your audience is knowledgeable in a particular area). You should also be concise and vary your wording. Sometimes it is better to use one very specific word instead of a whole sentence (for example in order to describe the way someone walks). [8]

Sample audio described materials

[edit | edit source]Audio description of buildings:

Audio description in trailers: "Frozen" trailer

Audio description in movies:The Interviewer

Audio description of paintings and sculptures: samples of audio descriptions are available on Beyond Sight: Database

Tasks for the readers

[edit | edit source]Task 1.

Pick one among provided pictures and create an audio description of the chosen work. Make sure to follow the guidelines outlined above. Once the audio description is finished, ask someone to listen to it (could be a visually-impaired person or a sighted one) and provide an opinion.

Task 2. Read fragments presented below and for each pair decide which fragment comes from a description for a sighted person and which for one adapted to the needs of the visually-impaired. Decide what are the characteristic features of audio description and what are the most important differences between each pair.

| Christ on the right, placing a bejeweled golden crown on the inclined head of the Virgin Mary, who sits on the left, her hands crossed over her chest. (...) Standing below and beside the figures, three miniature angels are aligned in two vertical rows. [7] | Gently, Christ places the ornate gold crown upon the Virgin Mary's slightly bowed head. Groups of musical angels watch from either side as she becomes the Queen of Heaven.[9] |

| We'll take a tour of the studio, starting at the viewer's left. In the left hand lower corner, the painting is taken up with an outlined rectangular table. Its near end - which is its short side - is cut off by the bottom edge of the picture. There are a few objects on the table. A white plate on which Matisse has painted a blue nude woman. A white box of blue pencils, sketchily painted in with visible sweeps of the brush. An empty wine glass, roughly outlined in pale blue against the red tabletop. A green glass vase with a round body and tall narrow neck. Out of the vase flows a long vine, with round green leaves. The plant creeps around a sculpture by Matisse, of a nude figure which sits near the far end of the table.[8] | Unassertive yellow lines create the outlines of Matisse’s furniture, creating objects out of the expansive red space. A grandfather clock sits approximately in the center of the composition, serving as a vertical axis that brings balance and harmony to the spatial discontinuities of the studio. The paintings and objects within the room, seemingly suspended in the sea of red, establish a sense of spatial depth by creating angles and perspective in an otherwise flat picture. They also give the eye a place to rest and bring a sense of harmony to the colors. Most of the objects are painted with whites, blues, and greens, colors that contrast and balance the thinly-applied red paint. There is also a tabletop that dominates the bottom left corner of the canvas, jutting out from the edge as if the viewer were next to it and looking down from a corner of the room. The spatial discontinuities of the table, the objects in the room, the chairs on the right side of the canvas, and the window on the left wall give the sense that this is the artist’s environment, dominated by creativity and color more than laws of natural order.[10] |

| This image comprises multiple focal points, including a carefully detailed genre scene in the foreground and distant, mist-enshrouded rocks at the center right of the composition. Along the mountains to the left, color and an atmospheric light recede into space, whereas the transition between the water and the sky appears more abrupt. It is a lone sailboat that seems to hover on the horizon, however, that prevails as the central focus of this romantic landscape. [11] | At left, the sky is blue with scattered, cottony clouds. And the indigo ocean water is calm, lapping against the shore. A group of people has congregated in the bottom left corner: a woman holds a child in her arms, a man props himself on his elbow, a boy in shorts struggles to carry a round basket. A man in a red vest stands with his back to us, and props his left hand on his hip. Behind them, brown fishing nets are stretched to dry over branches stuck upright in the sand. Behind them, at the water's edge, a man examines a few fishing boats pulled onto the sand.[8] |

Further Reading

[edit | edit source]Holland, Andrew. Audio Description in the Theatre and the Visual Arts:Images into Words. In: Audiovisual Translation. Palgrave Macmillian. 2009.

Snyder, Joel. Audio description. Visual Made Verbal. The American Council of the Blind. 2014.

External links

[edit | edit source]Vocaleyes

American Council of the Blind

Art Beyond Sight

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ http://www.acb.org/adp/ad.html#what

- ↑ http://audiodescriptionsolutions.com/about-us/a-brief-history-of-audio-description-in-the-u-s/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 http://www.artbeyondsight.org/mei/verbal-description-training/writing-verbal-description-for-audio-guides/

- ↑ http://www.tvhelp.org.uk/audes/theatre.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Holland, Andrew. Audio Description in the Theatre and the Visual Arts:Images into Words. In: Audiovisual Translation. Palgrave Macmillian. 2009. p. 180.

- ↑ http://audiodeskrypcja.pl/obrazSlowemMalowany.html

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 http://www.acb.org/adp/ad.html

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 http://www.artbeyondsight.org/mei/verbal-description-training/samples-of-verbal-description/#paintings

- ↑ http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/646/gentile-da-fabriano-coronation-of-the-virgin-italian-about-1420/

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L'Atelier_Rouge#cite_note-moma-1

- ↑ https://www.albrightknox.org/artworks/18631-marina-piccola-capri