Commercial diving/Diver Communications

Relevance: Scuba diving, Surface supplied diving, Surface oriented wet bell diving.

Required outcomes:

- Discuss diver communication in general

- Discuss diver communication including hard-wire and through water communications, voice communication protocols and the advantages of voice communication with the diver on an open channel

- Describe emergency diver communication including line signals

- Describe diver hand signals and communication on deck

Diver communication

[edit | edit source]

Diver communications are the methods used by divers to communicate with each other or with surface members of the dive team.

In professional diving, communication is usually between a single working diver and the diving supervisor at the surface control point. This is considered important both for managing the diving work, and as a safety measure for monitoring the condition of the diver. The traditional method of communication was by line signals, but this has been superseded by voice communication, and line signals are now mainly used in emergencies when voice communications have failed. Surface supplied divers often carry a closed circuit video camera on the helmet which allows the surface team to see what the diver is doing and to be involved in inspection tasks. This can also be used to transmit hand signals to the surface if voice communications fails.

Underwater slates may be used to write text messages which can be shown to other divers, and there are some dive computers which allow a limited number of pre-programmed text messages to be sent through water to other divers or surface personnel with compatible equipment. Slates may also be read by the surface via closed circuit video.

Hand signals are often also used by professional divers to communicate with other divers. There are also a range of other special purpose non-verbal signals, mostly used for safety and emergency communications.

History

[edit | edit source]The original communication between diver and attendant was by pulls on the diver's lifeline. Later a speaking tube system was tried, but it was not very successful. A small number were made by Seibe-Gorman, but the telephone system was introduced soon after this and since it worked better and was safer, the speaking tube was soon obsolete, and most helmets which had them were returned to the factory and converted. In the early 20th century electrical telephone systems were developed which improved the quality of voice communication. These used wires incorporated into the lifeline or air line, and used either headsets worn inside the helmet or speakers mounted inside the helmet. The microphone could be mounted in the front of the helmet or a contact throat-microphone could be used. At first it was only possible for the diver to talk to the surface telephonist, but later double telephone systems were introduced which allowed two divers to speak directly to each other, while being monitored by the attendant. Diver telephones were manufactured by Siebe-Gorman, Heinke, Rene Piel, Morse, Eriksson, Draeger and others. This system was well-established by the mid-20th century, and has been technologically improved, but is still in common use for surface-supplied divers using lightweight demand helmets and full-face masks.

More recently, through-water systems have been developed which do not use wires to transmit the signal. Manufacturers include Ocean Reef and Draeger. These allow communications over limited distances between divers and with the surface, usually using a push-to-talk system to conserve battery power.

Voice communications

[edit | edit source]

Both hard-wired (cable) and through-water electronic voice communications systems may be used with surface supplied diving. Wired systems are more popular as there is a physical connection to the diver for gas supply in any case, and adding a cable does not make the system any different to handle. Wired communications systems are still more reliable and simpler to maintain than through-water systems. The communications equipment is relatively straightforward and may be of the two-wire or four-wire type. Two wire systems use the same wires for surface to diver and diver to surface messages, whereas four wire systems allow the diver's messages and the surface operator's messages to use separate wire pairs.

A standard arrangement with wired diver communications is to have the diver's side normally on, so that the surface team can hear anything from the diver at all times except when the surface is sending a message. This is considered an important safety feature, as the surface team can monitor the diver's breathing sounds, which can give early warning of problems developing, and confirms that the diver is alive.

Divers breathing helium may need a decoder system also called unscrambling, which reduces the frequency of the sound to make it more intelligible.

Through water communications systems are more suitable for scuba as the diver is not encumbered by a communications cable, but they can be fitted to surface supplied equipment if desired. Most through water systems have a Push To Talk (PTT) system, so that high power is only used to transmit the signal when the diver has something to say This conserves battery power of the diver unit. For commercial diving applications this is a disadvantage, in that the supervisor can not monitor the condition of the divers by hearing them breathe.

These systems generally convert the auidio signal to an ultrasonic signal for transmission through the water, and then back to audio by the receiving unit.

Closed bells may have a through water communication system fitted as a backup.

Voice communication protocol

[edit | edit source]Underwater voice communication protocol is like radio communication protocol. The parties take turns to speak, use clear, short sentences, and indicate when they have finished, and whether a response is expected. Like radio, this is done to ensure that the message has a fair chance of being understood, and the speaker is not interrupted. When more than one recipient is possible, the caller will also identify the desired recipient by a call up message, and will also usually identify him/herself.

The surface caller should give the diver a chance to temporarily suspend or slow down breathing, or stop using noisy equipment, as breathing noise is often so loud that the message can not be heard over it.

Emergency diver communications and line signals

[edit | edit source]Rope signals

[edit | edit source]These are generally used in conditions of low visibility where a diver is connected to another person, either another diver or a tender on the surface, by a rope. These date back to the time of the use of Standard diving dress. Some of these signals, or pre-arranged variants, can be used with a surface marker buoy. The diver pulls down on the buoy line to make the buoy bob in an equivalent pattern to the rope signal. Effective rope signals need a free line without much slack, Before attempting a rope signal, the slack must be taken up, and the line pulled firmly. Most signals are acknowledged by returning the same signal, which shows that it was received accurately. Persistent failure to acknowledge may indicate a serious problem and should be resolved as a matter of urgency. There are several systems in use, and it is necessary to have agreement between diver and tender before the dive.

Rope signals used in the UK and South Africa:

Signals are combinations of pulls and bells, A pull is a relatively long steady tension on the line. Bells are always given in pairs, or pairs followed by the remaining odd bell. They are short tugs, and a pair is separated by a short interval, with a longer interval to the next pair or the single bell. The technique and nomenclature derive from the customary sounding of the ships bell every half-hour during the watches, which is also performed in pairs, with the odd bell last. One bell is not used as a diving signal as it is difficult to distinguish it from a jerk caused by temporarily snagging the line.

Attendant to diver:

General signals:

- 1 pull – Calling for attention, are you OK

- 2 pulls – I am sending down a rope's end (or other pre-arranged item)

- 3 pulls – You have come up too far, go back down till we stop you

- 4 pulls – Come up

- 4 pulls and 2 bells – Come to the surface immediately (often for surface decompression)

- 4 pulls and 5 bells – Come up your safety float line

Direction signals:

- 1 pull – Search where you are

- 2 bells – Go out along the jackstay or distance line, or straight out away from tender

- 3 bells – Facing shot or tender, go right

- 4 bells – Facing shot or tender, go left

- 5 bells – Come back towards shot or tender, or back along jackstay.

Diver to attendant:

General signals:

- 1 pull – To call attention, or have completed the last instruction.

- 2 pulls – Send down a rope's end or other pre-arranged item

- 3 pulls – I am going down

- 4 pulls – I wish to come up

- 4 pulls and 2 bells – Help me up

- 5 or more pulls – Emergency, pull me up immediately

- succession of 2 bells – I am fouled and need standby diver to assist

- succession of 3 bells – I am fouled but can get clear without assistance

- 4 pulls and 4 bells – I am trying to communicate on voice comms

Working signals:

- 1 pull – Hold on or stop

- 2 bells – Pull up

- 3 bells – lower

- 4 bells – Takeup slack on the lifeline or lifeline is too tight

- 5 bells – I have found, started or completed the work

Diver hand signals and light signals

[edit | edit source]Hand signals

[edit | edit source]Hand signals are a form of sign system used by divers to communicate when underwater. Hand signals are useful whenever divers can see each other, and some can also be used in poor visibility if in close proximity, when the recipient can feel the shape of the signaller's hand and thereby identify the signal being given. At night the signal can be illuminated by the diver's light. Hand signals are the primary method of underwater communication for recreational scuba divers, and are also in general use by professional divers, usually as a secondary method on surface supply and a primary method on scuba.

Divers who are familiar with a sign language may find it useful underwater, but there are limitations due to the difficulty of performing some of the gestures intelligibly underwater with gloved hands and often while trying to hold something.

The hand signals in general use are well summarised by the standard Recreational Scuba Training Council set of hand signals intended for universal use, which are taught to most divers in their entry level diving courses.

The RSTC hand signals provide the following information:

- I am out of breath! Hands indicate rising and falling chest.

- Go that way: Fist with one hand, thumb extended and pointing in the direction indicated.

- Go under, over or around: With palm down, hand motion used to indicate intended route to go under, over or around an obstacle.

-

Ascend, or I am going up: A fist is made with one hand, thumb extended upward, and hand is moved upward to emphasize direction of travel.

-

Descend, or I am going down: A fist is made with one hand, thumb extended downward, and hand is moved downward to emphasize direction of travel.

-

Something is wrong: An open hand with palm down and fingers apart is rocked back and forth on the axis of the forearm.

-

Are you OK? or I am OK! A circle is made with thumb and forefinger, extending the remaining fingers if possible.

-

The OK sign may be also be made without extending the fingers if wearing gloves.

-

I'm OK: Forming a large circle with both hands above the head: Used at the surface as the OK hand sign can be difficult to see from a distance.

-

I'm OK: Touching or tapping the top of the head with elbow extended sideways: Used at a distance when the hand sign may be difficult to see. Alternative surface "OK" signal.

-

Stop! Hand raised vertically with fingers together and palm facing the receiver.

-

Turn around: A forefinger extended vertically and rotated in a circular motion.

-

Which direction? A fist is make with one hand with extended thumb and the hand rotated on the axis of the forearm through 180° a few times to ask which way to go.

-

Boat: Hands cupped together.

-

Buddy reference. Used alone: Get with your buddy: Fists made with both hands, forefingers extended, and hands placed together with forefingers parallel and in contact.

-

Hold on to each other - Maintain physical contact: Both hands clasped together.

-

Who will lead, who will follow: One hand pointed at the diver who will lead then positioned in front of the body, pointing forward, then other hand pointed to the diver who will follow and positioned behind the first, direction indicated with forefingers.

-

Level off at this depth: Flat hand with palm down and fingers spread moved slowly side to side horizontally a few times.

-

Take it easy, Relax or Slow down: Flat hand with palm down moved slowly up and down a few times.

-

Give me air now (emergency implied): pointing to the mouth with thumb and fingers together, moving hand back and forth a short distance.

-

I'm out of air: "Cutting" or "chopping" throat with a flat hand.

-

Emergency! Help me now: Waving one or both arms in a wide arc. Used on the surface.

-

I don't know: Shrugging shoulders, arms bent, hands to each side, palms up.

-

Danger in that direction: Clenched fist pushed/pointed in the direction of the perceived hazard.

-

I am cold: Hugging chest and crossed arms in front of chest, upper arms grabbed by opposite hands.

-

Look: Point with two fingers to the eyes.

-

Think. or remember: Forefinger extended from fist, touching the side of the head at the temple.

-

I can't clear this ear: Pointing at the ear with forefinger.

Other widely used hand signals include:

- Hand cupped behind ear: "listen!"

- Pointing at someone changes the reference of the next signal from "I" to the diver pointed at.

- Flat hand swept over top of head, palm down: "I have a ceiling". This can indicate the diver has gone into decompression obligation or that there is a solid obstruction overhead. When ascending it means "stop here". (this is my decompression ceiling, or we are ascending too fast, or just generally stop ascending at this depth).

- Moving hand across torso in wave motion: "Current"

-

How much air do you have left?: One hand held flat, palm up, while index and middle finger of the other hand are placed on the palm.

-

There is air leaking from your equipment: Index finger is brought down to thumb in repetitive motion. Size of movement indicates severity of leak.

-

Cut the line: A request to another diver to cut a line or net. Often used in case of entanglement where the diver making the signal can not reach the point where the line should be cut.

-

Decompression or Safety stop: Signal is used to indicate that the diver intends to do a safety stop at that point.

-

Line, Line tangle or Cutting the line: The index finger is crossed with the middle finger to indicate line. If the hand is moved in a figure 8 it means a line tangle. Pointed down and rotated means a line tie off. In combination with the cutting signal it means cut the line.

-

Silt, or Silting: Palm and fingers down, thumb rubbed against the tips of the fingers

-

I have a cramp: Repeatedly clenching and unclenching fist, and point at cramped area

-

I am on reserve or I am on bailout gas or I am low on gas: Clenched fist held steady, about level with head or chest, palm side usually forward. Also may mean hold or stay there.

-

Time up - time to turn the dive and start heading back: Flat hand held roughly horizontal with tips of other flat hand's fingers touching the palm at right angles. Can also signify half of starting air remaining (in response to the "Pressure" signal).

-

Come and get me as soon as you can, but not an emergency: Signal to boat. Arm held straight up at the surface

-

Turn or terminate the dive. The thumb points upwards to indicate ascent, and the forefinger points towards the exit from a penetration dive. This signal may also mean that is the way out.

-

I am stuck: Thumb clenched between forefinger and middle finger of fist.

-

Ascend to stop: Thumb-up ascent signal below a flat hand, palm down.

Divers sometimes invent local signals for local situations, often to point out local wildlife. For example:

- I see a hammerhead shark: Both fists against sides of head

- I see a lobster: Fist with index and middle finger pointed out horizontally and alternately waggling up and down

- I see an octopus: Back of hand or wrist covering mouth, all fingers pointing outward from mouth and wiggling

- I see a shark: Hand flat, fingers vertical, thumb against forehead or chest

- I see a turtle: Hands flat one on top of each other, palms down, waving thumbs up and down together

Instructor signals:

- You (all) watch me. (usually before demonstrating a skill): Point at diver(s) with forefinger, point at own eyes with forefinger and middle finger, point at own chest with forefinger.

- You try that now, or do it again: Gesture with open hand palm up towards student after a demonstration of a skill.

Torch / flashlight signals

[edit | edit source]The focused beam of a torch can be used for basic signalling as well.

- OK signal: Drawing a circle on the ground in front of buddy.

- Attention please! Waving the torch up/down.

- emergency! Rapid, repeated, back and forth horizontal motion

Normally a diver does not shine a torch / flashlight in another diver's eyes but directs the beam to their own hand signal.

-

Light signal "OK"

-

Light signal "Attention"

-

light used to illuminate hand signal

Video communications

[edit | edit source]Closed circuit video is often fitted to the helmets of surface supplied commercial divers to provide information to the surface team of the progress of work done by the diver. This may allow the surface personnel to direct the diver more effectively to facilitate the completion of the task. This is always used with voice communication. The communications cables for these systems are part of the divers umbilical. Video may also be used to monitor the occupants of a closed diving bell.

Slates

[edit | edit source]Written messages on plastic slates can be used to convey complex messages with a low risk of misunderstanding. Slates are available in various sizes and are usually hard white plastic with a matte finish, suitable for writing on with a pencil. They can be stored in various ways, but in a pocket or bungeed to the wrist are popular methods. Clipped to the diver by a lanyard is another method, but there is a greater risk of entanglement. Slates may be used to record information to be used on the dive, such as decompression schedules, to discuss matters of importance for which hand signals are not sufficient, and to record data collected during the dive. Waterproof paper wet-notes are a compact equivalent, and pre-printed waterproof data-sheets and clip-board are routinely used by scientific divers for recording observations.

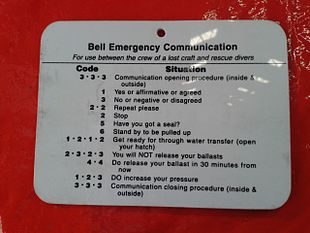

Light and gas signals for bell dives

[edit | edit source]There are emergency signals usually associated with wet and closed bell diving by which the surface and bellman can exchange a limited amount of information which may be critical to the safety of the divers. These signals are not generally applicable to a diver who is supplied directly by umbilical from the surface, but if the umbilical is snagged and rope signals cannot be transmitted, these signals may be provided by hat light flashes and helmet flush.

- 2 light flashes at the bell means that the surface is not receiving voice communications from the bell. The bellman responds by blowing down bell gas twice, creating two large distinct eruptions of bubbles that will be seen at the surface,then recalls the diver and prepares for surfacing.

- When the bell is ready to surface and the voice communications are not functioning, the bellman will blow down bell gas four times.

- If there is a problem during the ascent, a long continuous blowdown is the signal to stop.

Tap codes

[edit | edit source]

Tap codes, made by knocking on the hull, are used to communicate with divers trapped in a sealed bell or the occupants of a submersible or submarine during a rescue.

Miscellaneous emergency signals

[edit | edit source]A diver who has deployed a Delayed Surface Marker Buoy (DSMB) at the end of a dive may use a pre-arranged colour code to indicate if there is a problem. In some circles a yellow DSMB is considered an emergency signal, and red means OK. In most circles a second DSMB deployed on the same line will indicate a problem. A DSMB can also be used to carry up a slate with a message, but this is unlikely to be noticed unless a special arrangement has been made.

Diver down signals

[edit | edit source]Flags

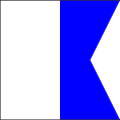

[edit | edit source]- International code flag "Alpha" (White hoist, blue swallowtail fly)

The American red with white diagonal Diver down flag is not legally recognised in South Africa

Light and shape signals

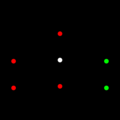

[edit | edit source]A vessel restricted in her ability to maneuver, except a vessel engaged in mine-clearance operations, shall exhibit:

- three all-round lights in a vertical line where they can best be seen. The highest and lowest of these lights shall be red and the middle light shall be white;

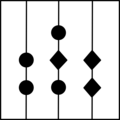

- three Day shapes in a vertical line where they can best be seen. The highest and lowest of these shapes shall be balls and the middle one a diamond;

- when making way through the water, a masthead light or lights, side lights and a stern light, in addition to the lights prescribed in sub-paragraph 1;

- when at anchor, in addition to the lights or shapes prescribed in sub-paragraphs 1 and 2, the light, lights or shape prescribed in International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea: Part C – Lights and shapes: Rule 30.

A vessel engaged in dredging or underwater operations, when restricted in her ability to maneuver, shall exhibit the lights and shapes prescribed in sub-paragraphs (1, 2 and 3 above) of this Rule and shall in addition, when an obstruction exists, exhibit: (Rule 27)

- two all-round red lights or two balls in a vertical line to indicate the side on which the obstruction exists;

- two all-round green lights or two diamonds in a vertical line to indicate the side on which another vessel may pass;

- when at anchor, the lights or shapes prescribed in this paragraph instead of the lights or shape prescribed in Rule 30.

Whenever the size of a vessel engaged in diving operations makes it impracticable to exhibit all lights and shapes prescribed in paragraph (above) of this Rule, the following shall be exhibited: (Rule 27)

- three all-round lights in a vertical line where they can best be seen. The highest and lowest of these lights shall be red and the middle light shall be white;

- a rigid replica of the International Code flag "A" not less than 1 metre (3.3 ft) in height. Measures shall be taken to ensure its all-round visibility.

-

International code flag "Alpha"

-

Light signals for a vessel undertaking underwater operations at night. The red lights indicate the obstructed side, green lights indicate clear side.

-

Shape signals for a vessel undertaking underwater operations during daylight. The balls indicate the obstructed side, diamonds indicate clear side.

Surface marker buoys

[edit | edit source]Permanently buoyant or inflatable surface marker buoys may be used to identify and/or mark the presence of a diver below. These may be moored, as a shotline, and indicate the general area with divers, or tethered to one of the divers by a line, indicating the location of the group to people at the surface. This type of buoy is usually brightly coloured for visibility, and may be fitted with one of the diving flag signals. A surface marker buoy (SMB) tethered to a diver is usually towed on a thin line attached to a reel, spool or other device which allows the diver to control the line length, so that excessive slack line can be avoided.

A deployable, or delayed surface marker buoy (DSMB) is an inflatable marker which the diver inflates while underwater and sends up at the end of a line to indicate position, and usually either that he or she is ascending, or that there is a problem. The use of a DSMB is common when divers expect to do decompression stops away from a fixed reference, or will be surfacing in an area with boat traffic, or need to indicate their position to the dive boat or surface team.

A group of moored surface marker buoys may be used to demarcate an area in which diving is taking place. This is more likely to be used by commercial, scientific or public service divers to cordon off a work or search area, or an accident or crime scene.

-

Delayed surface marker buoy with diver at the surface

-

A diver preparing to inflate a delayed surface marker buoy