Chemical Sciences

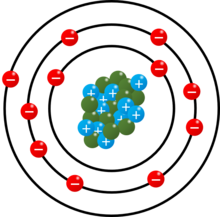

Chemical sciences is the study of, well, chemicals. We have discovered that everything is made up of atoms (which are in turn made up of the quarks, leptons and bosons, but this is a learning resource on chemical sciences, and not particle physics). Atoms are distinguished by the number of protons in its nucleus. It doesn't really matter what protons are, just that there are different types of atoms. Each atom has it's own 'personality' if you will. However, the types of atoms (called elements) in each column of the periodic table share similar traits. However, just like people, even those which are deemed similar enough aren't exactly the same.

Where atoms get their traits from

[edit | edit source]

Atoms have electrons orbiting it, while the nucleus keeps them in their rooms. The two innermost electrons get filled up first, making helium inert.

The second one has room for eight, then it runs out of rooms due to the the Pauli Exclusion principle, which states that fermions can't share a roommate.

The third shell then has 18 rooms, eight of which get filled up.

The fourth shell has room for 32 electrons, but the first two get filled, then the ten remaining empty rooms in the third shell. The fourth shell fills up with six more electrons, resulting in eight filled rooms.

The fifth shell, this time, has room for 50 electrons (currently, 18 rooms are vacant for every element. It's predicted they will be filled in the next row, or period, which is yet to be made). Two of the rooms in the fifth shell get filled up, then ten of the rooms in the fourth shell, then it precedes normally with six more filled electrons, again, resulting in eight filled rooms.

The sixth shell has room for even more electrons, but only 32 will ever be filled (by the time more electrons come, the element will have long since split apart). Two of the rooms in the sixth shell get filled up, then the 14 remaining empty rooms in the fourth shell, then ten of the rooms in the fifth shell, then six more electrons fill up the sixth shell, resulting in eight filled rooms.

The seventh shell, has a zillion rooms, but only 18 will ever be filled, due to the same reasoning as with the sixth shell. Two of the seventh shell rooms get filled up, then 14 of the rooms in the fifth shell, then ten of said rooms in the sixth, then the seventh shell gains six more electrons, resulting in eight filled rooms.

Elements like to have exactly eight electrons in its outer shell (except hydrogen and helium, they're weirdos), causing the similar personalities of the elements. This is why, for example, the halogens, which have 7 electrons (and are on the second to last column of the periodic table), and the alkali metals, which have one electron, go so well together. The alkali metal gives an electron to the halogen to satisfy both parties. Generally, metals are altruistic, noble gases will put up a fight to preserve their collection, and non-metals are greedy.

The reason why their personalities aren't exactly the same is because the nucleus of the atoms have a harder time managing electrons that are far away, so for example, xenon should be inert, but fluorine comes along really desperate for an extra electron. Xenon puts up a fight, but fluorine ends up winning, resulting in xenon difluoride.

Activity

[edit | edit source]- Assign students an element. This can be any element in the periodic table

- Give them the corresponding number of marbles to represent the outermost electrons

- Give them the task of trying to get 8 marbles (if they're a non metal), give away every marble (if they're a metal) or to try to keep all eight marbles (if they're a noble gas)

- If they shared, taken, or gave away marbles, ask them to stay together, preferably with hands held

- If the students are assigned with heavier elements, ask them to care less about having eight or none, to help others get eight or none.

- If a person gets more than eight marbles, remove eight of them (they're now inner electrons)

- Observe as the children (mostly) make valid compounds