Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2023/Fall/Section33/Joe Vaughn

Overview[edit | edit source]

Joe Vaughn was interviewed by Ida Price in 1938 as a part of the Federal Writers Project

Life in New Iberia, LA[edit | edit source]

In 1861, Joe Vaughn was born in Canada. At an early age, Vaughn immigrated to New Iberia, Louisiana. Vaughn lived in New Iberia for the next 63 years. In New Iberia, Joe Vaughn raised a family with his wife Ezora. Joe and Ezora were members of the French-descended Cajun Community, which grew in Louisiana during the late 19th century. The couple would have ten children: five boys and five girls. Sadly, five of their children died early on. In New Iberia, Joe Vaughn's hobbies included hunting, fishing, and farming. The Vaughns sustained their family by selling their shrimp and crop yields.

Life in Bayou La Batre, AL[edit | edit source]

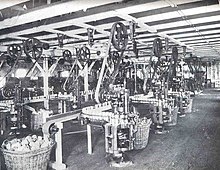

Around 1925, the Vaughns moved to Biloxi, Alabama. The family left New Iberia when they realized that they could not compete with the massive companies that sell canned shrimp and seafood products. They did not stay long in Biloxi as they heard that the working conditions at the Dorgan McPhillips Packing Plant in Bayou La Batre, Alabama were better. For nine months in the year, Joe and Ezora work as shrimp and oyster canners, earning $4-$6 a week. In 1937, Joe only received 3 months of work from Dorgan McPhillips.

Social Context[edit | edit source]

Shrimping on the Gulf Coast[edit | edit source]

"Shrimping was probably carried on in Louisiana by the Indians before the French came and by the French since 1718, but the industry did not begin until 1867 when the first canning factory began operation." (Aquinas, 1962) [1] Before the sixties, shrimp wasn't a primary export for the region. Shrimp were caught to sell at local markets. "Shrimp were first packed in the Gulf of Mexico area. G. W. Dunbar of New Orleans, canned shrimp as early as 1867 but had difficulty with blackening and discoloration. He solved this problem in 1875 with the invention of a can lining which aided greatly in overcoming blackening. Shrimp packing soon became and remains today the principal fishery canning industry of the Gulf coast." (NOAA,1939) [2] As the United States begins to consume canned seafood, regions with high populations of shellfish began to industrialize. "From a total Gulf of Mexico catch of 534, 000 pounds valued at sixteen million dollars in 1880, Louisiana production increased to 6,810,000 pounds in 1887. From 1887 until 1908 the total Gulf catch remained relatively stable, increasing only moderately from 6,810,000 pounds in 1887 to 8,581,000 in 1908. By 1913 the catch grew to 10.5 million pounds valued at slightly over one-half million dollars." (Aquinas, 1962) Throughout the 20s, the nationwide yield of shrimp was steadily increasing until the Great Depression. The industry bounced back to their status quo by 1931, and to continue grow throughout the 1930s, outside of 1937 where the market briefly dropped. (NOAA, 1939)

The Cajun Diaspora[edit | edit source]

Acadie was discovered by French explorers in 1604. The territory, in modern Nova Scotia, was conquered by Great Britain in 1713. The occupied Acadians would frequently clash with the British Forces. In 1955, the Acadians were expelled from the region by the British during Le Grand Derangement. Many of the exiles were unhappy in their new homes and moved on. "Some of them found their way to south Louisiana and began settling in the rural areas west of New Orleans. By the early 1800s, nearly 4000 Acadians had arrived and settled in Louisiana." (National Parks Service, 2022) [3] The Acadians who settled in Louisiana are more commonly known as Cajuns. Following the seperation between the Cajuns and the other Acadians, the groups began to assume different identities. "Unlike the New England Acadians who had abandoned their land to move to the city and find employment within factories, Louisiana Acadians had, like the idealized Acadian assiduously promoted by so many of elite at this time, espoused a rural and Roman Catholic way of life. They had like their northern counterparts prior to their Renaissance, long lived in isolation, preserving what would be considered their old Acadian traditions." (Acadiensis, 2016) [4] Cajuns maintained their identities as French Catholics in the Protestant American South. This made Louisiana an anomaly as they were the only state with a significant Cajun population. "In south Louisiana, unlike most of the southern United States, Catholicism is the norm, and its sacraments, feasts, and calendar permeate many aspects of life... Under the influence of the region’s Latin European and African heritage, unique manifestations of the faith have emerged. Various Catholic holidays are celebrated in distinctive ways in south Louisiana, from the region’s rural Mardi Gras traditions to the tradition of washing and painting the tombs and crypts in local cemeteries for All Saints’ Day. (HNOC, 2020) [5]

Footnotes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Becnel, Thomas Aquinas. “ A History Of The Louisiana Shrimp Industry, 1867-1961.” LSU.Edu, Louisiana State University, 1962, repository.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9340&context=gradschool_disstheses.

- ↑ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE CANNING OF FISHERY PRODUCTS. Washington DC: NOAA, 1939. https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy-pdfs/leaflet78.pdf.

- ↑ “From Acadian to Cajun.” National Parks Service, July 22, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/jela/learn/historyculture/from-acadian-to-cajun.htm.

- ↑ MCNALLY, CAROLYNN. “Acadian Leaders and Louisiana, 1902-1955.” Acadiensis 45, no. 1 (2016): 67–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24877227.

- ↑ “What Does It Mean to Be Cajun? 12 Stories to Understand This Identity.” The Historic New Orleans Collection, December 11, 2020. https://www.hnoc.org/publications/first-draft/what-does-it-mean-be-cajun-12-stories-understand-identity.

References[edit | edit source]

Becnel, Thomas Aquinas. “ A History Of The Louisiana Shrimp Industry, 1867-1961.” LSU.Edu, Louisiana State University, 1962, repository.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9340&context=gradschool_disstheses.

“From Acadian to Cajun.” National Parks Service, July 22, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/jela/learn/historyculture/from-acadian-to-cajun.htm.MCNALLY, CAROLYNN. “Acadian Leaders and Louisiana, 1902-1955.” Acadiensis 45, no. 1 (2016): 67–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24877227.

MCNALLY, CAROLYNN. “Acadian Leaders and Louisiana, 1902-1955.” Acadiensis 45, no. 1 (2016): 67–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24877227.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE CANNING OF FISHERY PRODUCTS. Washington DC: NOAA, 1939. https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy-pdfs/leaflet78.pdf.

Prine, Ida. . “Life in a Shrimping and Oyster Chucking Camp.” UNC.EDU. 11/29/38. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/03709/id/1020/rec/1.

“What Does It Mean to Be Cajun? 12 Stories to Understand This Identity.” The Historic New Orleans Collection, December 11, 2020. https://www.hnoc.org/publications/first-draft/what-does-it-mean-be-cajun-12-stories-understand-identity.