Evidence-based assessment/Rx4DxTx of PTSD

HGAPS is finding new ways to make psychological science conferences more accessible!

Here are examples from APA 2022 and the JCCAP Future Directions Forum. Coming soon... ABCT!

~ More at HGAPS.org ~

Resources for the assessment and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

[edit | edit source]Diagnostic Interviews and Screening Criteria

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

[edit | edit source]Exposure to traumatic experiences can lead to the development of distressing symptoms which often cause significant impairment in many aspects of an individual’s life. Due to the heavy reliance on self-identification or the need for early intervention after distressing events take place, such as the events on September 11, 2001, it is imperative that PTSD assessment and treatment is provided to individuals who need it in order to moderate lifetime impairment. The goal of this article is to address the multiple aspects of PTSD to help with identification of potential cases. The role of exercise as a form of treatment will also be discussed.

Diagnostic Criteria, Prevalence, and Comorbidity

[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Criteria

[edit | edit source]With the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013, PTSD was moved from an anxiety disorder to a new category: Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders[1]. This change is due to a new distinction between disorders dependent upon experiencing a traumatic event, such as PTSD, and disorders that may or may not develop following a traumatic event, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). PTSD must begin with exposure to a specific traumatic event which requires “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence”[1]. Exposure to a traumatic event must also be experienced in a way pre-defined by the DSM with either direct exposure, witnessing trauma to others, indirect exposure through trauma experience of a family member, or, as a new addition to DSM-5, through repeated exposure to aversive details of traumatic events relating to one’s work, such as a mortician in the military[1]. The specification of the latter form of exposure is in contrast with DSM-IV which took a broader approach. Under the DSM-IV, those exposed to violence on TV or natural disaster coverage by the media would be classified as trauma-exposed thus increasing the reported numbers for PTSD prevalence[1]. Symptoms for PTSD are clustered into the following groups: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity, where one avoidance symptom is required for a diagnosis alongside qualifying exposure as discussed above[1]. In contrast to the DSM-5, which is aimed at a broad definition of PTSD and full coverage of its presentation, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) classifies PTSD as being defined by at least six individual symptoms for a more simplified focus on the disorder[2]. These symptoms include dissociative flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, avoidance of external reminders, avoidance of thoughts and feelings associated with traumatic event[3]. This is in contrast to the ICD-10 which included 13 symptoms for a PTSD diagnosis[3]. The ICD-11 was proposed in 2019 and has yet to come into full effect; however, changes from ICD-10 to ICD-11 have substantial impact on PTSD diagnosis. ICD-11 excluded

multiple symptoms from the PTSD classification list such as cognitive and affective symptoms (included in both the ICD-10 and the DSM-5) as well as sleep disturbances and trigger-related behavior, leading to less diagnoses yet increased identification of more severe cases of PTSD[3]. Although both assessment tools are aimed at helping clinicians diagnose PTSD, studies have shown that the ICD-11 may be more comprehensive and representative when figuring out prevalence rates of PTSD[2]. Although the ICD-11 may capture the true essence of PTSD with its limited criteria, it is not well-suited to diagnosing PTSD in children and adolescents. The DSM-5, however, was published with significant changes to PTSD diagnosis in younger populations in order to make up for this gap. These changes include lowering the number of symptoms needed for a diagnosis, including developmentally sensitive symptom presentation such as more behavior-oriented expression through things like play and other avenues[4]. The DSM-5 developed a different set of criteria for children under age six based research that considered developmental differences in symptom expression of PTSD. [5] The DSM-IV criteria were developed from adult samples only, despite PTSD being reported in children and adolescents, so change was necessary. [5] This research suggested that a common trauma for children is loss of a parent/caregiver, whether it be through death, abandonment, or foster care treatment, since children need that relationship to feel safe.[5] It also suggested an age-related subtype for preschool children that lowers the threshold for avoidance symptoms.[5] The DSM-5 accepted this research by creating a separate criterion for children six and under and by placing child-caregiver-related loss as the main source of trauma for this age group. It also focuses on behaviorally expressed symptoms and lowered the threshold for some symptom clusters to be more developmentally accurate.[5] The change in language now used in the DSM-5 has increased prevalence rates for children which may reflect more accurate rates than before[4].

Table 1: Key Symptoms and Clusters for the Diagnosis of PTSD Using DSM-5 and ICD-11[6]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

* Intrusive memories must be vivid and accompanied by feelings of being immersed in the traumatic event in the present | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prevalence

[edit | edit source]The National Comorbidity Survey Replication assessed that among 5,692 Americans aged 18 and older, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 6.8%[7]. General prevalence rates vary across countries with 0.3% found in China and 6.1% found in New Zealand[7], although differences in assessment methods can create discrepancies in comparison of rates. Sex differences have been found among PTSD rates with women reporting lifetime rates 2x higher than men[8]. This difference is found in adolescents and adults (adolescent girls 6.3% and boys 3.7%, adult women 10.4% and men 5%)[7][8]. It was also found that 75% of individuals with PTSD experienced symptom onset before age 40[7].

Using a nationally-representative sample from The National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), a research study sought to examine the racial/ethnic differences of the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) on PTSD.[9] The sample of 10,123 adolescents ranged from ages 13-18, with 4.2% of the adolescents interviewed experiencing lifetime PTSD. Overall, higher ACE scores were linked to greater odds of experiencing PTSD at some point in life across White (non-Hispanic), Black, and Hispanic adolescents. However, Black and Hispanic adolescents were less likely to have lifetime PTSD compared to White non-Hispanic adolescents.[9] Notably, the total mean ACE scores were significantly higher for Black and Hispanic adolescents (M = 2.54 for both), suggesting that these groups face a greater cumulative burden of adverse childhood experiences compared to White non-Hispanic (M = 2.04) and “Other” adolescents (M = 2.15).[9] It is quite important to mention that the data used for the study was collected between 2001-2004, but the NCS-A is still the largest data pool available for adolescent mental health information obtained from a structured clinical interview.[9]

A 2022 literature review analyzed the prevalence and risk factors of PTSD in American youth from minority backgrounds. Sources of traumatic experiences include "historical/generational trauma, immigration and acculturation stressors, natural and manmade disasters, experiences of discrimination, family violence, [community violence]", as well as the COVID-19 pandemic. [10]

Common Comorbidities

[edit | edit source]

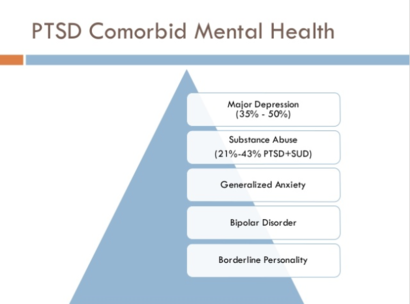

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder has many co-occurring diagnoses. Of those with PTSD, around 80-90% have another disorder while 2/3 have two or more disorders[11]. Common co-occurring disorders are major depression, anxiety, substance use[12], borderline personality, and forms of psychosis[11]. Some PTSD individuals may also experience suicidal thoughts, dissociations, and other disruptions in functioning[11]. A large concentration in research has been on corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in relation to PTSD. CRF is released from the hypothalamus in the brain in order to mediate stress responses by increasing secretion of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary gland[13]. After increasing ACTH in the brain, the adrenal gland becomes stimulated subsequently increasing secretion of cortisol and adrenaline[13]. This is also known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA-axis). With PTSD being a stress-related disorder, it is no wonder why CRF has been a focus in research. In relation to psychosis, PTSD with comorbid psychosis has been argued to be a more severe form of PTSD and has been supported by additional brain research[13]. Sautter and colleagues looked at differences in cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) between individuals with PTSD and psychotic symptoms, PTSD alone, and healthy individuals. They found that individuals with PTSD and psychotic symptoms had significantly higher levels of CRF supporting the idea that increased stress responses in the form of specific disorders in associated with increased levels of CRF[13]. Research on CRF has implications in relation to other disorders aside from PTSD which may help to explain the comorbid nature of PTSD and other disorders. For depression, studies have found increased CRF levels in individuals with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) emphasizing the role of a hyperactive HPA-axis[14][15]. Research in relation to anxiety has revealed that CRF has a higher affinity for receptor 1 rather than receptor 2, meaning that CRF will bind to receptor 1 before it binds to receptor 2[14]. This is important to anxiety because in mouse models it has been found that CRF receptor 1 is generally anxiogenic, or anxiety inducing, and receptor 2 is anxiolytic, or anxiety reducing[14]. With increased CRF found in PTSD patients, it is no wonder why anxiety and depression are commonly co-diagnosed as CRF in the brain is more often binding with receptor 1 and consequently increasing anxiety while also producing an overactive HPA-axis. The possibility that CRF may underlie primary and secondary diagnoses could have implications for treatment as targeting CRF systems may show promise for new research.

Prognosis and Developmental Course

[edit | edit source]

There are many protective and risk factors for the development of PTSD. In early childhood, psychological trauma and abuse, having mentally ill parents, and experiencing environmental stressors like unsafe or war-ridden neighborhoods are all risk factors for later development of PTSD[16]. Low socioeconomic status may also be a risk factor due to its likelihood of introducing additional stressors into an individual’s life[16]. SES, a distal risk factor, interacts with proximal risk factors, more salient stressors such as family instability, in that if a child experiences a distal risk factor but few proximal risk factors, they are considered to have more resilience[16]. This idea of resilience is key in studying PTSD development as they are many factors that go into what makes an individual more resilient than others. Social support is an important factor in fostering resiliency in individuals who experience trauma. Research on war veterans and those exposed to ongoing traumatic experiences have found that those with intact and strong social networks of support displayed fewer PTSD symptoms[16]. Research into hardy personality traits have also shown that higher scores on the hardiness scale moderate the effects of war-related stress[16]. Thus, personality traits and individual resources also play a role in PTSD development. The onset of PTSD may occur directly after the traumatic experience or it could be delayed with some experiencing symptoms months later[17]. Due to PTSD being a complex disorder with multiple types of presentations and differing courses of development between individuals, it is hard to predict PTSD development outcomes from baseline[18]. For instance, one study of PTSD patients found that 37% of patients with symptoms at 12 months post-trauma did not have symptoms at 3 months post-trauma[18]. This supports the idea that it is difficult to set a course for PTSD, especially when accounting for risk and protective factors that take hold post-trauma.

PTSD can onset at any age after age one as long as a trauma occurs, and it varies in how it manifests during the developmental course. Children and adolescents exhibit a wide range of stress reactions based on their developmental stage. Younger preschool-aged children often exhibit more overt aggression, may show repetitive play or drawing of the event, and may perform behavioral re-enactments. [19] Their symptomology is different because many avoidance symptoms require complex introspection, which is too complicated for young children to put into words, and why they are more likely to express their symptoms through play [20]. School-aged children begin to exhibit reactions more similar to those manifested by adults since they can understand more about the situation and its consequences.[19]Factors such as race, class, and gender impact prognosis as well[21]. Minority racial and ethnic groups, people of low socioeconomic status, and females typically report higher levels of PTSD symptoms. This could be due to the fact that those groups often have additional stressors that worsen their symptoms. [22]

PTSD has a poor prognosis if left untreated. PTSD symptoms can affect all aspects of an individual’s life. Decreased social support, avoidant coping styles and lower self-esteem are all common consequences of untreated PTSD[16]. Suicide rates are high among PTSD individuals compared to their non-PTSD counterparts.[7] Substance use disorder is common on PTSD individuals as turning to drugs and alcohol can sometimes become a method for coping. [17][23] Neurologically, individual’s with PTSD have been found to have decreased hippocampal volume and activation, as well as dysfunctional connectivity to other cortices.[24] Dennis and colleagues found less functional anisotropy, often represented by less myelination and fiber density which can affect the speed and effectiveness of neuronal communication, within specific areas of the corpus callosum like the tapetum.[24] The corpus callosum is a structure that connects the left and right hippocampus and may be involved in the hippocampal problems seen in PTSD patients. The tapetum is one of the last structures to develop within the corpus callosum, starting around the age of 14, which may have important implications for early traumatic experiences and vulnerability to later PTSD development.[24] With treatment, PTSD has a better prognosis. Richardson and colleagues found that substantial gains can be made in symptom reduction and even remission with treatment given over a 2-year period.[25] However, depressive symptom severity and experiencing previous treatment failures were predictors of treatment outcome.[25] It is important to recognize those who need treatment for PTSD as consequences can be highly impairing but long-term treatment can help make life more manageable.

Evidence Based Assessment

[edit | edit source]

Assessment and diagnosis of PTSD can be done using DSM-5 or ICD-11 criteria or by self-report questionnaires. There are many self-report questionnaires for PTSD; however, those with fewer questions and simplified responses and scoring methods were better accepted and performed well against structured interviews or more complicated questionnaires.[26] Some of these questionnaires include the Impact of Event Scale, the Trauma Screening Questionnaire, the Posttraumatic Stress Symptom Scale, and others which ask questions pertaining to the experiencing and severity of PTSD symptoms.[26] CAPS, or the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, is an assessment measure created specifically for PTSD. This assessment method uses a semi-structured interview to determine the intensity of PTSD. However, CAPS is somewhat time consuming and has been used primarily for veterans who have experienced combat-trauma.[27] New research is showing that the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) may be a good alternative to improve diagnostic utility. The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure, versus a 30-item structured interview for CAPS-5, that follows DSM-5 diagnostic rules and has been found to exhibit strong reliability and validity. [28] This research supports the use of PCL-5 in PTSD detection and shows that it correlates positively and significantly with CAPS-5 scores while being a cheaper and more feasible option to increase detection.[28] These are supported measures for PTSD and may offer more comfort to clients if they are being asked to recall difficult experiences; however, they are intended to be used with mental health professionals in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of each individuals’ situation and are likely to be used in combination with formal interviews and diagnostic methods.[29]

Another form of PTSD assessment may involve physiological measures. Studies have found that, when exposed to personalized trauma-related stimuli, individuals with PTSD have increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and skin conductance.[30] These physiological tests can also be used to look at startle responses and ability to concentrate, to test hyperarousal.[30] Looking at physiological responses may be more informative of the possible presence of PTSD and may aid in recognizing those who are at risk for developing the disorder. These measures, however, are not as useful when conducting tests on those whose symptom severity is lower than average.[30] These individuals are still at risk of being underdiagnosed and require more intensive assessment methods such as the ones described above. It is important to note that assessment for child and adolescent populations is not the same as for adult populations. Since untreated PTSD can lead to substance use disorder, suicidality, and poor mental health, it is important to catch those who have been exposed to trauma as early as possible.[31] Common symptoms such as anger, impulsivity, and attention issues may be misdiagnosed as conduct disorder or attention deficit disorders, which puts youth at risk for not receiving the treatment they need.[31] The Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 (CPSS-5), adapted from DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, was developed to identify symptoms and assess the severity of PTSD in children aged 8 to 18 years. Testing has shown the CPSS-5 to have high validity and reliability, demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting PTSD in youth populations within this age range.[31]

While the afore mentioned assessments (and similar measures) have exhibited usefulness in diagnosing older children, clinical interviews with the child and the parent or self-report scales are not as efficient for younger children. For children aged six and under, clinicians typically rely more on caregiver reports. A widely-used assessment tool for this age group is the Young Child PTSD Checklist (YCPC), which includes items that represent the DSM-5 "Young Child" criteria.[32] However, La Greca and Danzi note that there is some concern with parents/caregivers being the sole respondents for young children, since parents are known to underestimate PTSD symptoms in their children even at older ages.[32] Research has shown that the most ideal course of action is to integrate information from multiple informants (parent/caregiver, teacher, self, .etc), since each party will have unique insight that will help with treatment planning. Additionally, it is suggested that clinicians routinely ask children and adolescents about exposure to common traumatic events, since such events may go unidentified or underestimated. Following a trauma endorsement by a child, the clinician should then screen for PTSD symptom.[32]

Table 2: Starter Kit of Measures for Screening and Assessing PTSD in Youth[33]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Evidence Based Treatment

[edit | edit source]Treatment for PTSD comes in many forms. It is important to understand which treatment modalities are more or less effective, as well as the various side effects of treatment on different individuals. What works for one patient may not always work for another. There are many ways to treat PTSD, most of which come after a semi-structured interview or some other form of assessment. When determining a direction for treatment, a few factors must be considered, such as comorbid disorders, how treatment might affect a family as a whole, and the degree to which the patient is committed to recovering. A patient who is not dedicated to their recovery will be less likely to see results from a highly involved form of treatment or therapy. Due to the many barriers of receiving treatment, such as cost, time, accessibility, and the general willingness to see a therapist, many forms of therapy will be examined[34]. By considering a wide range of treatments, an individual is more likely to find a treatment that is both appealing and effective to them as an individual.

There are a few different kinds of therapy that have been effective for treating PTSD. Among these are medication, eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), trauma focused-cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), and prolonged exposure therapy (PE). Medication-based treatment relies most heavily on selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s) above other medications with meta-analyses showing that medication impacts all symptom clusters rather than targeting a specific PTSD symptom (i.e. re-experiencing, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal).[23] However, treatment with medication is needed long-term as relapse rates are high with short-term SSRI treatment[23]. There is also not substantial evidence to support the idea that medication alone can be used as treatment for PTSD, thus a combination of medication and another treatment modality is most effective.[23] EMDR therapy is based on the notion that bilateral stimulation from eye movement will help reprocess emotional and traumatic memories while maintaining a relaxed state.[35] The reprocessing of memories is based on of the adaptive information processing model which posits that individuals with PTSD have maladaptively processed and stored information in a way that leaves them vulnerable to outside triggers.[35] These triggers have the ability to resurface a stored memory along with its associated physical and psychological symptoms.[35] EMDR has been found to show a rapid decline in distress, depression and anxiety in just one session with medium to large effect sizes.[36] While EMDR has many theories about underlying mechanisms, all of which disagree with each other, the World Health Organization and National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence have deemed it the PTSD treatment of choice[35]. TF-CBT is another superior therapy in the treatment of PTSD. This form of therapy is focused on cognitive restructuring of distorted thoughts and beliefs while the client focuses on the traumatic stimulus.[37] The TF-CBT model consists of 12 to 25 sessions (depending on the severity of the trauma) divided into 3 treatment phases: stabilization, trauma narration and processing, and integration.[38] In adolescent/child cases, parental involvement is integral to the model and they receive the same amount of treatment time as their children.[38] TF-CBT was determined to do significantly better than waitlist immediately after treatment as well as 4, 8, and 12 months post treatment[39]. This form of treatment was also better than treatment as usual[40][41]. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of EMDR versus TF-CBT found that these treatments are relatively similar in reducing PTSD symptoms with both have strong positive effect sizes; however, EMDR may be more feasible as it does not require homework and has a shorter overall treatment duration[39][37]. PE is based on imaginal exposure in which the client is asked to bring up a memory along with its associated emotions and sensations while processing the memory in order to reduce fear[11]. PE has been shown to reduce PTSD symptoms while also reducing common comorbid symptoms like depression, anxiety, and negative cognitions[11]. Treatment for youth and adolescents with PTSD needs to be developmentally sensitive; however, TF-CBT and prolonged exposure for adolescents (PE-A) have been found to be effective treatments for this population because of their focus on reducing negative trauma-related cognitions[42][43].

In addition to interventions that occur well after the traumatic event, some researchers focus on prevention measures to reduce the likelihood of PTSD before a traumatic event occurs, or right after it occurs before an official diagnosis can be made. Researchers identify what they call secondary preventions, which is intervention that begins with early disturbing symptoms that may indicate future risk.[44] They studied the impacts of the Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention (CFTSI), which involves four sessions with the child and caregiver.[44] The CFTSI focuses on two key risk factors for future development of PTSD: poor social support and poor coping skills.[44] This intervention helps by increasing communication between the child and the caregiver about what is going on and by providing behavior skills to both the parent and the child to help with coping.[44] The children that were in the CFTSI group showed significantly lower posttraumatic and anxiety scores, resulting from a decrease in avoidance and re-experiencing, so it has promise as an effective early intervention.[44]

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Exercise

[edit | edit source]One unusual but effective form of treatment for PTSD symptom reduction is physical activity. A systematic review and meta-analysis done by Rosenbaum and colleagues found that physical activity reduced PTSD symptoms with a small to moderate effect size[45]. It was also found that physical activity helped to reduce depression and anxiety -related comorbid symptoms[45]. These effects have been found in multiple populations. In female adolescents, aerobic exercise was found to reduce PTSD, anxiety and depression symptoms and the reduction in PTSD was maintained months after stopping exercise[46]. A study on college students found that exercise was a mediator between PTSD symptoms and negative health outcomes, supporting the idea that physical activity can reduce PTSD symptoms and possible health-related consequences[47]. In veteran populations, exercise was found to be associated with fewer PTSD symptoms and smaller likelihood of developing symptoms[48][49]. The neurological changes have the most important impact when it comes to physical activity effects on PTSD symptoms. In a mouse model of PTSD, Shafia and colleagues found an association between physical activity and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)[50]. BDNF is a vital protein for neuronal survival, growth, and maintenance as well as a synaptic plasticity, a key component of learning and memory[51]. In the stress induced mice, reduced BDNF and increased cell death was found along with dysregulation of the HPA-axis[50]. Exercise was found to increase BDNF, which led to cognitive improvements, decreased cell death and counteracted HPA-axis dysfunction[50]. The animal model used for this study is highly reliable and valid as it maps onto human PTSD so these findings may also be found among human interventions with physical activity.

One neurobiological factor that plays a large role in the improvement of PTSD symptoms is the endocannabinoid system. When exercising, cannabinoid receptors are activated, which leads to improved regulation of neurotransmitter activity. This process results in improved mood and cognitive functioning, as well as reduced stress [52]. In terms of PTSD, this neurotransmitter regulation has been shown to improve symptoms of hyperarousal, such as irritability and hypervigilance. It is important to note that these studies of PTSD and exercise have focused on aerobic exercise, and effects might vary for other forms of exercise. Aerobic exercise has been shown to activate the endocannabinoid system more so than other exercise. Apart from neurobiological factors in improving PTSD symptoms with exercise, there are also psychological factors, such as the benefits of teamwork in group sports and the role of motivation in aerobic or non-aerobic exercise. A case study by Ley, Barrio, and Koch (2017) [53]. showed that exercise and sports improved a general sense of motivation that extended into areas of life beyond the sport itself. This perspective can be also considered to look at the role of exercise as it related to existing treatment methods. Studies have shown that exercise paired with or completed prior to receiving therapy for PTSD appears to be more effective than exercise only or therapy only. This may be due in part to the exposure to internal arousal that exercise provides [54]. While exercising, the heart rate is elevated as it is when experiencing anxiety. Similar to exposure therapy, when patients exercise and do not experience any harm from the internal arousal that mimics anxiety, they become desensitized to these internal cues. It is important to consider the underlying physiological and neural mechanisms of the relationship between exercise and PTSD. Research has suggested that regular aerobic exercise has mental health benefits for people with PTSD.[55] A study found that PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms decreased among all exercise groups compared to control groups.[55] However, their data did not support the hypothesis that attentional focus to the somatic sensations from the exercise is a primary mechanism underlying the results.[55] If attentional focus if not at work, it could possibly be that participants felt a sense of accomplishment, experienced behavioral activation, or had neurochemical changes (i.e. endorphin rush) that helped alleviate their symptoms.[55] There needs to be further inquiry on the mechanisms underlying the positive effects of exercise, but even without that it would be beneficial to include physical activity in PTSD treatments.

Resources

[edit | edit source]| Resource | Information |

|---|---|

| Department of Veteran Affairs | Stemming from U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, this resource is the National Center for PTSD. Although this resource isn’t specifically for veterans, it is a widely used and well-known resource geared towards helping those with PTSD who quite often are veterans. This website lays out PTSD services, information for families and friends, and other important information. |

| NAMI | From the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), this resource provides an overview on PTSD, information on different treatment methods and support information for those with PTSD as well as those around the individual who want to help. |

| NIMH | The National Institute of Mental Health provides general information about symptom presentation and treatment for PTSD as well as risk factors and discussions of PTSD development in different populations. |

| Triangle Springs | Triangle Springs is an in-patient and out-patient facility in NC focused on those who are 18 and older. With treatments such as CBT, DBT, trauma focused therapy this facility is aimed at developing coping mechanisms and other valuable tools. |

| Access Family Services | Access Family Services is aimed at helping children and adolescents with different treatment methods along with family participation efforts. Although adults are also seen here, this is a good resource for younger children with PTSD. |

| ADAA | ADAA (Anxiety and Depression Association of America) provides a self screening, which could be a useful preliminary step to understand if an appointment with a mental health professional may be necessary. |

| RAINN | The Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network is a resource focused on those who have developed PTSD after sexual trauma. The site includes both symptom description as well as a helpline. |

| Effective Child Therapy | Effective Child Therapy provides helpful summaries of symptoms and treatments for youth with psychological symptoms and disorders. This is a good resource for children and adolescence with PTSD. |

See also

[edit | edit source]

Share this page by clicking the following social media and interactive platforms:

![]() Email |

Email |

![]() Facebook |

Facebook |

![]() Twitter |

Twitter |

![]() LinkedIn|

LinkedIn|

![]() Mendeley

Mendeley

Clicking the Mendeley button will offer to import all of the citations in the references below into your library.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Pai, A., Suris, A. M., & North, C. S. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behavioral Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hansen, M., Hyland, P., Karstoft, K.-I., Vaegter, H. B., Bramsen, R. H., Nielsen, A. B. S., Armour, C., Andersen, S. B., Høybye, M. T., Larsen, S. K., & Andersen, T. E. (2017). Does size really matter? A multisite study assessing the latent structure of the proposed ICD-11 and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup7), 1398002. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1398002

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Barbano, A. C., van der Mei, W. F., Bryant, R. A., Delahanty, D. L., deRoon-Cassini, T. A., Matsuoka, Y. J., Olff, M., Qi, W., Ratanatharathorn, A., Schnyder, U., Seedat, S., Kessler, R. C., Koenen, K. C., & Shalev, A. Y. (2019). Clinical implications of the proposed ICD-11 PTSD diagnostic criteria. Psychological Medicine, 49(3), 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718001101

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). DSM-5 changes: implications for child serious emotional disturbance. CBHSQ Methodology Report. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519708/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Scheeringa, M. S., Zeanah, C. H., & Cohen, J. A. (2011). PTSD in children and adolescents: Toward an empirically based algorithma. Depression and Anxiety, 28(9), 770–782. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20736

- ↑ E.A. Youngstrom, M.J. Prinstein, E.J. Mash, & R.A. Barkley (Eds.), Assessment of Childhood Disorders (5th Edition). New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Gradus, J. L. (2017). Prevalence and prognosis of stress disorders: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Clinical Epidemiology, 9, 251–260. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S106250

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Olff, M., Langeland, W., Draijer, N., & Gersons, B. P. R. (2007). Gender differences in Posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Elkins, Jennifer; Briggs, Harold E.; Miller, Keva M.; Kim, Irang; Orellana, Roberto; Mowbray, Orion (2019-10-15). "Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Nationally Representative Sample of Adolescents". Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 36 (5): 449–457. doi:10.1007/s10560-018-0585-x. ISSN 0738-0151. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10560-018-0585-x.

- ↑ Pumariega, Andres J.; Jo, Youngsuhk; Beck, Brent; Rahmani, Mariam (2022-04-01). "Trauma and US Minority Children and Youth". Current Psychiatry Reports 24 (4): 285–295. doi:10.1007/s11920-022-01336-1. ISSN 1535-1645. PMID 35286562. PMC PMC8918907. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-022-01336-1.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 van-Minnen, A., Zoellner, L. A., Harned, M. S., & Mills, K. (2015). Changes in comorbid conditions after prolonged exposure for PTSD: A Literature Review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(3), 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0549-1

- ↑ Kilpatrick, Dean G.; Ruggiero, Kenneth J.; Acierno, Ron; Saunders, Benjamin E.; Resnick, Heidi S.; Best, Connie L. (2003). "Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents.". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71 (4): 692–700. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692. ISSN 1939-2117. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Sautter, F. J., Bissette, G., Wiley, J., Manguno-Mire, G., Schoenbachler, B., Myers, L., Johnson, J. E., Cerbone, A., & Malaspina, D. (2003). Corticotropin-releasing factor in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with secondary psychotic symptoms, nonpsychotic PTSD, and healthy control subjects. Biological Psychiatry, 54(12), 1382–1388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00571-7

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Sanders, J., & Nemeroff, C. (2016). The CRF system as a therapeutic target for neuropsychiatric disorders. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 37(12), 1045–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2016.09.004

- ↑ Krohg, K., Hageman, I., & Jørgensen, M.B. (2008). Corticotropic-releasing factor (CRF) in stress and disease: a review of literature and treatment perspectives with special emphasis on psychiatric disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 62(1), 8-16. doi: 10.1080/08039480801983588

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Agaibi, C. E., & Wilson, J. P. (2005). Trauma, PTSD, and resilience: a review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 6(3), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838005277438

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Institute of Medicine. (2014). Treatment of Posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK224878/

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Bryant, R., O'Donnell, M., Creamer, M., McFarlane, A., Silove, D. (2013). A multisite analysis of the fluctuating course of Posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(8), 839-846. doi:10/1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1137

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dyregrov, A., & Yule, W. (2006). A Review of PTSD in Children. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 11(4), 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00384.x

- ↑ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). DSM-5 Child Mental Disorder Classification. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519712/

- ↑ Marshall, Grant N.; Schell, Terry L.; Miles, Jeremy N. V. (2009-12). "Ethnic Differences in Posttraumatic Distress: Hispanics’ Symptoms Differ in Kind and Degree". Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 77 (6): 1169–1178. doi:10.1037/a0017721. ISSN 0022-006X. PMID 19968392. PMC 2821595. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2821595/.

- ↑ La Greca, A., & Danzi, B. A. (2020). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. In E. A. Youngstrom, M. J. Prinstein, E. J. Mash, & R. Barkley (Eds.), Assessment of Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (5th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Stein, D., Ipser, J., Seedat, S., Sager, C. & Amos, T. (2006). Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Systematic Review. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002795.pub2

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Dennis, E., Disner, S., Fani, N., Salminen, L., Logue, M., Clarke, E., Haswell, C., Averill, C., Baugh, L., Bomyea, J., Bruce, S., Cha, J., Choi, K., Davenport, N., Densmore, M., du Plessis, S., Forster, G., Frijling, J., Gonenc, A., Morey, R. (2019). Altered white matter microstructural organization in posttraumatic stress disorder across 3047 adults: results from the PGC-ENIGMA PTSD consortium. Molecular Psychiatry. https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1038/s41380-019-0631-x

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Richardson, J., Contractor, A., Armour, C., Cyr, K., Elhai, J., & Sareen, J. (2013). Predictors of long-term treatment outcomes in combat and peacekeeping veterans with military-related PTSD. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(11), 1299-1305. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08796

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 National Collaborating Centre of Mental Health. (2005). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of ptsd in adults and children in primary and secondary care. NICE Clinical Guidelines, 26, chap. 8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56499/

- ↑ Foa, Edna B.; Tolin, David F. (2000). "Comparison of the PTSD symptom scale–interview version and the clinician-administered PTSD scale". Journal of Traumatic Stress 13 (2): 181–191. doi:10.1023/A:1007781909213. ISSN 1573-6598. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1023/A%3A1007781909213.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Geier, T. J., Hunt, J. C., Nelson, L. D., Brasel, K. J., & deRoon‐Cassini, T. A. (2019). Detecting PTSD in a traumatically injured population: The diagnostic utility of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 36(2), 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22873

- ↑ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, 57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207188/

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Orr, S. P., & Roth, W. T. (2000). Psychophysiological assessment: clinical applications for PTSD. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00340-2

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Foa, E. B., Asnaani, A., Zang, Y., Capaldi, S., & Yeh, R. (2018). Psychometrics of the child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1350962

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 La Greca, A., & Danzi, B. A. (2020). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. In E. A. Youngstrom, M. J. Prinstein, E. J. Mash, & R. Barkley (Eds.), Assessment of Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (5th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- ↑ E.A. Youngstrom, M.J. Prinstein, E.J. Mash, & R.A. Barkley (Eds.), Assessment of Childhood Disorders (5th Edition). New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- ↑ Dorsey, Shannon; McLaughlin, Katie A.; Kerns, Suzanne E. U.; Harrison, Julie P.; Lambert, Hilary K.; Briggs, Ernestine C.; Cox, Julia Revillion; Amaya-Jackson, Lisa (2017-05-04). "Evidence Base Update for Psychosocial Treatments for Children and Adolescents Exposed to Traumatic Events". Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 46 (3): 303–330. doi:10.1080/15374416.2016.1220309. ISSN 1537-4416. PMID 27759442. PMC PMC5395332. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1220309.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Landin-Romero, R., Moreno-Alcazar, A., Pagani, M., & Amann, B. (2018). How does eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy work? A systematic review on suggested mechanisms of action. frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1395. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01395

- ↑ Shapiro, F. 2014. The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. The Permanente Journal, 18(1), 71-77. doi: 10.7812/TPP/13-098

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Seidler, G. & Wagner, F. (2006). Comparing the efficacy of EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Medicine, 36, 1515-1522. doi:10.1017/S0033291706007963

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Cohen, Judith A.; Mannarino, Anthony P. (2022-01). "Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children and Families". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 31 (1): 133–147. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2021.05.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1056499321000304.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Cooper, R., & Lewis, C. (2013). Psychological therapies for chronic Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003388.pub4

- ↑ Jensen, T. K., Holt, T., Ormhaug, S. M., Egeland, K., Granly, L., Hoaas, L. C., Hukkelberg, S. S., Indregard, T., Stormyren, S. D., & Wentzel-Larsen, T. (2014). A randomized effectiveness study comparing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with therapy as usual for youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(3), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.822307

- ↑ Goldbeck, Lutz; Muche, Rainer; Sachser, Cedric; Tutus, Dunja; Rosner, Rita (2016). "Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Eight German Mental Health Clinics". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 85 (3): 159–170. doi:10.1159/000442824. ISSN 0033-3190. https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/442824.

- ↑ Cary, C. & McMillen, J. (2012). The data behind the dissemination: a systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(4), 748-757. https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.003

- ↑ McLean, C. P., Yeh, R., Rosenfield, D., & Foa, E. B. (2015). Changes in negative cognitions mediate PTSD symptom reductions during client-centered therapy and prolonged exposure for adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 68, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.03.008

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Berkowitz, S. J., Stover, C. S., & Marans, S. R. (2011). The Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention: Secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(6), 676–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02321.x

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Rosenbaum, S., Vancampfort, D., Steel, Z., Newby, J., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2015). Physical activity in the treatment of Post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017

- ↑ Motta, R. W., Kuligowski, J. M., & Marino, D. M. (2010). The role of exercise in reducing childhood and adolescent PTSD, anxiety, and depression. National Association of School Psychologists. Communique; Bethesda.

- ↑ Rutter, L. A., Weatherill, R. P., Krill, S. C., Orazem, R., & Taft, C. T. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, depressive symptoms, exercise, and health in college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021996

- ↑ Whitworth, J. W., & Ciccolo, J. T. (2016). Exercise and post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans: a systematic review. Military Medicine, 181(9), 953–960. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00488

- ↑ LeardMann, C. A., Kelton, M. L., Smith, B., Littman, A. J., Boyko, E. J., Wells, T. S., & Smith, T. C. (2011). Prospectively assessed Posttraumatic stress disorder and associated physical activity. Public Health Reports, 126(3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491112600311

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Shafia, S., Vafaei, A., Samaei S., Bandegi, A., Rafiei, A., Valadan, R., Hosseini-Khah, Z., Mohammadkhani, R., Rashidy-Pour, A. (2017). Effects of moderate treadmill exercise and fluoxetine on behavioural and cognitive deficits, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and alternations in hippocampal BDNF and mRNA expression of apoptosis – related proteins in a rat model of post-traumatic stress disorder. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 139, 165-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2017.01.009

- ↑ Genetics Home Reference. (2020, March 17). BDNF gene. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/BDNF

- ↑ Crombie, K. M., Brellenthin, A. G., Hillard, C. J., & Koltyn, K. F. (2018). Psychobiological Responses to Aerobic Exercise in Individuals With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(1), 134–145 https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22253

- ↑ Ley, C., Barrio, M. R., & Koch, A. (2017). “In the Sport I Am Here”: Therapeutic Processes and Health Effects of Sport and Exercise on PTSD: Qualitative Health Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317744533

- ↑ Hegberg, N. J., Hayes, J. P., & Hayes, S. M. (2019). Exercise Intervention in PTSD: A Narrative Review and Rationale for Implementation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00133

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 Fetzner, M. G., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2015). Aerobic Exercise Reduces Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.916745