Motivation and emotion/Book/2018/Suicidality in the elderly

What are the main contributing factors to suicidality in the elderly

and what preventative strategies can be recommended?

Overview

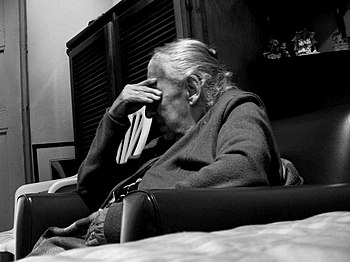

[edit | edit source]To take one’s own life is both devastating for the one enacting and for those left behind. For the family and friends, the aftermath of a loved one's passing affects us all in different ways. Suicide, is one of the more devastating causes of death. In addition to sadness, a wide range of emotions can overcome us. Suicide can invoke emotions of regret, disappointment, guilt and even anger. One might ask why is suicide different and why does it make many of us so uncomfortable. This could perhaps resonate from a lack of understanding of how suicidality or suicide ideation comes to mind in some individuals but not others. Why do some attempt suicide while others do not? What elements of a senior citizens' life might drive them to the point of desiring death over life? What is it in older adulthood and/or retirement that would motivate someone to take their own life?

Why do senior citizens so often feel driven to suicidal ideation and what can society do to help those who need the help the most? By understanding where suicidal ideation stems from in the elderly, perhaps we can tackle the issue at the roots and eliminate it before it begins.

Suicide is terrible when it happens to anyone; however, it is surprisingly prevalent in those aged 60 and above. What are the contributing factors that drive so many within this category to commit that final act? Worldwide approximately 800,000 deaths occur each year by suicide according to WHO (2018). According to the ABS (2018) around 21% of all deaths by suicide in Australia are by adults over the age of 60. Within, the United States suicide by those in the 75 plus category had the second highest prevalence of suicide (AFSP, 2016) (see Figure 1).

These numbers are crucial to outlining the importance of developing preventative strategies to suicidal thinking in the elderly. By looking at theories of suicidal ideation as well as the livelihoods of elderly citizens. It may be possible to assess their suicide risks by identifying what aspects of their lives may be motivators and/or protective elements to suicide. To treat something it is first important to understand its origins and then, develop methods of combating the issue at hand. For further reading of suicide prevalence in different age groups see: Suicidality across the lifespan (2018).

|

Focus questions

|

Relevant theories for suicidality in the elderly

[edit | edit source]There are numerous theories that try to explain suicide generally, but however, others look specifically at why elderly citizens are so prone to suicide (Stanley et al., 2015). When an elderly person takes an attempt at their life, it can come as a shock to the many who know them and often it feels as though this action is inexplicable and "out of the blue". From looking at theories and motivators behind suicidality in the elderly we can perhaps gain a better understanding of how to implement prevention strategies for those who need it.

|

Suicidality - What is it?

Firstly, it is important to understand what suicidality is and what it means when applied to the elderly. Suicidality, is often referred to as suicide ideation and can be explained as the "idea of suicide", and it can vary in severity and can consist of "passive life ending thoughts through to active intended suicidal ideas and plans" (Malfent et al., 2009). That is to wish for death and or thoughts of taking one's own life. |

Two very prominent theories that can help us to understand suicidality in the elderly are Interpersonal-psychological theory and Integrated motivational - Volitional model of suicide.

Interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide

[edit | edit source]Interpersonal theory (IPT) outlines three core elements to suicidal ideation: perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness and acquired capability (Joiner, 2005). By having an accumulation of these elements, suicidality increases, and the elderly can be particularly at risk due to a higher capability for suicide (Circirelli, 2001).

Perceived burdensomeness is to feel as though your presence is an inconvenience and a liability to those around you (Van Orden et al., 2010). A person who feels this way might believe that their death means more to those around them than their life does (Stanley et al., 2015). This is particularly true if the elderly member feels to be a burden to younger generations (Jahn & Cukrowicz, 2011). Malfent et al., (2009) found locus of control and self-efficacy to be protective factors for suicidal ideation and inhibition in these areas can increase perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation. Therefore, the elderly are at risk of identifying themselves to be a burden because they may feel less able and require more assistance than in their past.

Thwarted belongingness refers to experiences of loneliness, social isolation and inability to fit in (Joiner, 2005). This theory proposes that the second contributor to suicidal ideation is the belief that one does not belong to any valued groups or relationships (Cukrowicz et al., 2011). A review of relevant literature investigating suicide by the elderly identified that social isolation, death, and loss of loved ones, can lead to a depreciated sense of social relevance and loss of meaning in one's existence (Minayo & Cavalcante, 2015).

Acquired capability is the final necessary step to attempted/completed suicide. The theorists behind the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide propose that a combination of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness is only explanatory to suicidal thinking and not suicide attempt (Van Orden et al., 2010). Suicide is not easy, even for those who have all the ingredients for suicidal thinking, because even with suicidal ideologies there is still a biological desire to live (Stanley et al., 2015). Perhaps, this could explain why completed suicide is so high in the elderly because older persons are much less averse to death than the young (Circirelli, 2001). The elderly often use more violent means of suicide than younger generations resulting in more completed suicides (Conwel et al., 2002).

Integrated motivational - volitional model

[edit | edit source]

The Integrated motivational - volitional model (IMV) model of suicide is designed to map the process with which suicidal ideation develops into plans and actions of suicide (Stanley et al., 2015). The theory identifies three stages that attempt to explain the process of how suicidality develops. Entrapment is a key underlying feature of the IMV model that can lead to suicidal behaviour. "Entrapment is triggered by feelings of inescapable defeat and humiliation" (Stanley et al., 2015). The three stages are; the pre-motivational, the motivational, and the volitional phase.

Pre-motivational phase: The first stage identifies the precursors (or triggers) to suicidal ideation. These triggers can consist of biological, genetic and cognitive factors that influence suicide risk (O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018). These are essentially the underlying causes that generate the feeling of entrapment which depending on the person can evolve into suicidal motivation.

The Motivational phase: the second stage is the point at which the accumulation of triggers develops into suicidal ideation (i.e., active thoughts of suicide). The sense on entrapment can evolve into acute suicidality if in a correlation with personality traits such as; social perfectionism, pessimism, and negative affect (O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018).

Volitional phase: The third and final stage of the IMV model is the volitional stage. This stage refers to the accumulation of all elements that may lead to attempted suicide and self harm. This theory acknowledges the importance of acquired capability as noted in the IPT model; however, it also acknowledges further volitional moderators such as environmental, physiological, social and psychological effects (O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Each of these elements moderate whether suicidal ideation develops into suicidal action. A common risk to suicidal volition is that of exposure to suicide and death. Bereavement from loss of loved ones, sleep disturbance, and disability are more common in the elderly population and are risk factors for depression and suicide (Vaid, 2015) (see Figure 2). Each of these commodities can act as volitional moderators for suicide; loss as social moderator, disability as physiological, and sleep disturbance as a psychological moderator. Sleep disturbance is a known contributor to poor cognitive function as well as depressive symptoms (Fulke & Vaughan, 2010).

Motivational factors and protective factors for suicidality in the elderly

[edit | edit source]| “ | The most terrible poverty is loneliness, and the feeling of being unloved. - Mother Teresa |

” |

Successful ageing

[edit | edit source]According to Adorno et al. (2016) successful ageing refers to longevity, independent functioning and the absence of morbidity. Research has identified that general emotional regulation should improve with age through means of savouring; which is the ability to think positively on past events (Smith & Bryant, 2016). Successful ageing is generally measured by using to quality of life (QoL) scores which can be observed through self-measurement instruments (Bowling & Iliffe, 2006). Speculatively, if successful ageing does not occur then poor QoL (or life satisfaction) could increase suicidality in the elderly (Malfent et al., 2009). Successful ageing pays close attention to social satisfaction, individual capability, and problem solving ability (Malfent et al., 2009). Elements of successful ageing that act as protective factors for suicidality in the elderly are; purpose in life, self-efficacy and autonomy.

Purpose in Life

[edit | edit source]It is easy to see how having a purpose in life can be a preventative measure for suicidal thinking when it is broken down. Purpose in life refers to having meaningful lives, as well future direction and goals (Ryff, 2014). Having purpose in life is also seen as a health protective behaviour which can assist in the prevention of a number of physiological as well as psychological disabilities (Kim, Strecher & Ryff, 2014). Disability is often correlated with depressive symptoms as well as suicidal ideologies (Borges, 2014). Thus, by increasing life purpose in later life, suicidal ideation could potentially be decreased.

Self-efficacy and autonomy

[edit | edit source]Self efficacy refers to an individuals perceptions of their independence in life. Common issues in the elderly with suicidal attempts are that of illness, physical dependence, pain, and the loss of independence (Minayo & Cavalcante, 2015). All elements that impact upon self efficacy. Poor self efficacy can lead to perceived burdensomeness from the IPT of suicide from earlier in this chapter. To be autonomous is to have freedom of choice in ones life. For the ageing population, this sense of autonomy can be taken away when diagnosed with disability, placed into nursing homes, and retirement (Malfent et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2014). Malfent and colleagues (2009) found an internal locus of control to be a protective factor for suicidality in the elderly. What this means is that by identifying that you as an individual have the power to make decisions and to change your path, then you are less likely to experience suicidal thinking. The opposite is an external locus of control, which is when one feels they have no control over their outcomes.

Physical and mental health

[edit | edit source]A reoccurring contributor throughout this chapter is that of how burdensomeness can affect suicidality in the elderly. When an elderly person feels that they are a burden on society and/or their families, suicidality tends to increase (see Figure 3). One study of disabilities in a Chinese sample of elderly communities identified a number of disabilities that can impact suicidal thinking and attempted suicide. Zhang et al., (2016) measured disabilities that affect daily living, these included; shopping, cooking, housekeeping, finances, etc. What their study identified is that when the elderly had any disability in those categories, risk of suicide attempt was 3 times more likely. Additionally co-morbidity of 5 or more disabilities of daily functioning resulted in 5 times the suicidal thinking (Zhang et al., 2016). These physical in-capabilities can be explained by looking back at poor self-efficacy and loss of autonomous ability in the elderly and both IPT and IMV theories.

In addition to physical disadvantages, mental disorders are also correlated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Borges et al., 2014; Podea & Blaj, 2014). A systematic review of studies by Kanwar et al., (2013) identified that there is a significant relationship between anxiety disorders and suicidality throughout any age. The authors speculate that the causal relationship between anxiety and suicidality is unclear; however, anxiety can be a precursor to further psychological distress and disorder comorbidity (e.g., depression). This relationship between anxiety and suicide is important to understanding suicidality in the elderly; generalised anxiety disorder is one of the most prevalent disorders in the elderly, even more so than major depressive disorder (Podea & Blaj, 2014). Additionally, Conwell, Duberstein and Caine, (2002) argue the importance of affective disorders (mood and depressive disorders) in suicidality within the elderly. They state that affective disorders are one of the more potent risk factors for suicide in this demographic.

Life Transition, Retirement and Social Influences

[edit | edit source]

As people age, their lifestyles are subject to change in ways they may be unprepared for. A big factor in the lives of the ageing population is that of retirement, life transition and social identity. Many retirees struggle with their social identities after retirement perhaps due to the loss of workplace friendships as well as poor maintenance and formation of new social groups (Lam et al., 2018; Shiba et al., 2017). Formation and participation within multiple recreational social groups is evidenced to decrease risk of affective disorders and retirement dissatisfaction (Lam et al., 2018). If the elderly do not have sufficient social support, they are likely to be influenced negatively in areas of self-esteem, purpose, coping mechanisms and a sense of belonging (Thoits, 2011). It can understood how crucial social support can be for the prevention and coping with suicidality in the elderly (see Figure 4).

Cultural differences

[edit | edit source]There are cultural differences in the impact of social memberships, specifically differences between collectivist cultures and individualistic cultures. Lam et al., (2018) identified that collectivist members, (predominately, Asian, African, and South Americans) are much less likely to seek help from within their social groups due to their enhanced fear of being a burden on the group. Furthermore, they are less likely to benefit from social support due to their felt burdensomeness to the group. Additionally, collectivist members are less likely to leave social groups that are not beneficial to them as they think collectively for the group benefit over their own. Alternatively individualistic members are much more likely to pick and choose groups that are beneficial to themselves and or leave unrewarding groups resulting in a higher satisfaction in receiving and seeking social support because there is less likely to be a felt burdensomeness in individualistic cultures (Lam, et al., 2018). This is not to say that collectivist members are less likely to experience benefit from social groups, only that their effects are likely to be lower than individualistic members.

Socioeconomic status

[edit | edit source]Studies have shown that those who originate from a lower socioeconomic status more often have lower mental health in retirement (Shiba et al., 2017). A contrasting study of U.S. retirees found that those with a higher socioeconomic status and wealth were much more likely to be satisfied with their lives in retirement (Kim & Ekerdt, 2016). This could potentially be explained by the stresses of financial losses for lower socioeconomic retirees, that may result in precursors or triggers for suicidal ideation as explained by IMV theory.

Religious views

[edit | edit source]Suicidality can occur within anyone in the aged population, religious views can influence the effects of this suicidality and stigma. Kirby (2001) states that religions such as Catholicism hold negative perspectives on suicidal intention. What this means is that those who hold strong catholic beliefs are less likely to seek help due to fear of condemnation which in turn could result in a higher suicidality rate because help is perceived as more unobtainable.

|

Stop and thinkǃ

Both interpersonal psychological theory and integrated motivational - volitional theory of suicide can be help to explain why issues with successful ageing, retirement, and social identity may be motivators for suicidality in the elderly! |

Preventative strategies

[edit | edit source]Suicidality in the elderly is a significant issue for current generations and statistically, it does not seem to be improving (WHO, 2018; ABS, 2018; ASFP, 2016). It is crucial for the current generations to develop sound preventative measures for the elderly, to tackle the issue presented in this chapter. For a more thorough exploration of current suicide prevention techniques see; Suicide prevention (2014). One of the biggest issues with suicidality prevention in the elderly is that suicide for older generations is often more premeditated, unpredictable and more often results in successful suicide (Zhang et al., 2015). The premeditated element of suicide in the elderly poses an issue for the predictability of suicidality, and current older generations are much less likely to discuss their concerns and/or seek help like younger generations (Kirby, 2001). By taking an understanding of what elements in the lives of the elderly can increase suicidality, prevention plans can work to combat these issues. It is important for friends, families, and carers to understand the risks of suicidality and to identify what areas life are crucial to decreasing risk.

The key to suicidality intervention in the elderly is that of early identification which can be followed by implementation strategies that focus on enhancing the successful ageing process. In a study of suicide prevention strategies for the elderly in Korea, Sun (2016) identified that depression screening tests was one of the most effective methods when followed by intervention strategies and therapies. By identifying the early onsets of depressive and/or affective disorders, strategies can be implemented to combat suicidality (Conwell et al., 2002). People in caring relationships with the elderly (with and without disability) should place take an understanding of autonomy and self-efficacy as well as being aware of how over-dependence can impact mental health in the elderly (Malfent et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2014; Minayo & Cavalcante, 2015). Additionally, prevention strategies should be aware of IPT theory and take a comprehensive and empathetic approach to perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness and how the elderly have particularly high acquired capability for suicide. Furthermore, IMV theory can help researchers to understand the development of suicidality in the elderly and focus on implementing strategies to combat this. Numerous studies place importance on facilitating beneficial social and family relationships, hobbies, and overall purpose in life (Lam et al., 2018; Thoits, 2011). Intervention strategies should place emphasis on how meaningful social groups can enhance a sense of belonging and contentment and therapeutic alliances should work to enhance savouring ability (positive memories) the combat pessimism in the elderly (Smith & Bryant, 2016).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]This chapter has sought to explain the importance of understanding suicidality in the elderly. Suicidality in the elderly is an often misunderstood and complicated issue that has many elements that require attention for future intervention. From understanding how suicidality comes to develop in the elderly, and what areas can help to improve the livelihoods of those at risk we can combat this issue better. Education is one of the best interventions for suicide and according to lifeline crisis support, three steps to suicide intervention are one: asking, two: listening, and three: seeking help if needed. This simple procedure is the primary idea in this chapter, in that being empathetic and understanding why someone might have suicidal ideologies, we as individuals and as a society can intervene much more effectively and reduce risk for the elderly.

|

Test your knowledge

|

See also

[edit | edit source]- Assisted dying motivation (Book chapter, 2018)

- Collectivism (Wikipedia)

- Elder abuse motivation (2018) (Book chapter, 2018)

- Individualism (Wikipedia)

- Suicidality across the lifespan (2018) (Book chapter, 2018)

- Suicidality and motivation (2013) (Book chapter, 2013)

- Suicide prevention (2014) (Book chapter, 2014)

References

[edit | edit source]Ansello, E. F. (2011). The Most Terrible Poverty [Editorial]. Age in Action, 26(1).

Borges, G., Acosta, I., & Sosa, A. L. (2014). Suicide ideation, dementia and mental disorders among a community sample of older people in Mexico. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(3), 247-255. doi:10.1002/gps.4134

Bowling, A., & Iliffe, S. (2006). Which model of successful ageing should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing. Age and Ageing, 35(6), 607-614. doi:10.1093/ageing/afl100

Circirelli, V. (2001). Personal meanings of death in older adults and young adults in relation to their fears of death. Death Studies, 25(8), 663-683. doi: 10.1080/713769896

Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P. R., & Caine, E. D. (2002). Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry, 52(3), 193-204. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01347-1

Cukrowicz, K. C., Cheavens, J. S., Van Orden, K. A., Ragain, R. M., & Cook, R. L. (2011). Perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 26(2), 331-338. doi:10.1037/a0021836

Fulke, P., & Vaughan, S. (2010). Sleep deprivation: Causes, effects and treatment. New York: Nova Science.

Jahn, D. R., & Cukrowicz, K. C. (2011). The Impact of the Nature of Relationships on Perceived Burdensomeness and Suicide Ideation in a Community Sample of Older Adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(6), 635-649. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278x.2011.00060.x

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kanwar, A., Malik, S., Prokop, L. J., Sim, L. A., Feldstein, D., Wang, Z., & Murad, M. H. (2013). The Association Between Anxiety Disorders And Suicidal Behaviors: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. Depression and Anxiety. doi:10.1002/da.22074

Kim, E. S., Strecher, V. J., & Ryff, C. D. (2014). Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(46), 16331-16336. doi:10.1073/pnas.1414826111

Kim, H. (2016). The effects of socioeconomic status on retirement satisfaction among baby boomers in the usa. The Gerontologist, 56(Suppl3), 187-188. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw162.732

Kirby, M. (2001). Letter to the Editor. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(9), 920-920. doi:10.1002/gps.417

Lam, B. C., Haslam, C., Haslam, S. A., Steffens, N. K., Cruwys, T., Jetten, J., & Yang, J. (2018). Multiple social groups support adjustment to retirement across cultures. Social Science & Medicine, 208, 200-208. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.049

Main Features - Intentional self-harm, key characteristics. (2018). Retrieved October 12, 2018, from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/3303.0~2017~Main%20Features~Intentional%20self-harm,%20key%20characteristics~3

Malfent, D., Wondrak, T., Kapusta, N. D., & Sonneck, G. (2009). Suicidal ideation and its correlates among elderly in residential care homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(8), 843-849. doi:10.1002/gps.2426

McCue, R. E., & Balasubramaniam, M. (2018). Rational Suicide in the Elderly Clinical, Ethical, and Sociocultural Aspects. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Minayo, M., & Cavalcante, F. (2015). Suicide attempts among the elderly: A review of the literature (2002/2013). Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 20(6), 1751-1762. doi:10.1590/1413-81232015206.10962014

O'connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170268. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575-600. doi:10.1037/a0018697

Podea, D., & Blaj, M. (2014). Anxiety and the risk of suicide in elderly. European Psychiatry, 29.

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10-28. doi:10.1159/000353263

Shiba, K., Kondo, N., Kondo, K., & Kawachi, I. (2017). Retirement and mental health: Does social participation mitigate the association? A fixed-effects longitudinal analysis. BMC Public Health, 17(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4427-0

Smith, J. L., & Bryant, F. B. (2016). Successful Aging. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 665-665. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw162.2705

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Rogers, M. L., Hagan, C. R., & Joiner, T. E. (2015). Understanding suicide among older adults: A review of psychological and sociological theories of suicide. Aging & Mental Health, 20(2), 113-122. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1012045

Suicide Statistics. (2016). Retrieved October 12, 2018, from https://afsp.org/about-suicide/suicide-statistics/

Suicide. (2018, August 24). Retrieved October 12, 2018, from http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

Sun, H. (2016). Suicide prevention efforts for the elderly in Korea. Perspectives in Public Health, 136(5), 269-270. doi:10.1177/1757913916658622

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145-161. doi:10.1177/0022146510395592

Vaid, N. (2015). Depression in the elderly. InnovAiT: Education and Inspiration for General Practice, 8(9), 555-561. doi:10.1177/1755738015596030

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010, April). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575-600. doi:10.1037/a0018697

Zhang, W., Ding, H., Su, P., Duan, G., Chen, R., Long, J., Du, L., Xie, C., Jin, C., Hu, L., Sun, Z., Gong, L., Tian, W. (2015). Does disability predict attempted suicide in the elderly? A community-based study of elderly residents in Shanghai, China. Aging & Mental Health, 20(1), 81-87. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1031641

External links

[edit | edit source]- Crisis Support (Lifeline Australia)

- How to make a safety plan (Reach out Australia)

- Mental Health Assistance (Beyond Blue)

- World Health Organisation, 2018.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics: Causes of death

- American foundation for suicide prevention, 2016)

Interesting resources