Motivation and emotion/Book/2016/Immunisation motivation in childhood

What motivates parents to vaccinate or not vaccinate their children?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Immunisation is a process whereby an organism is made immune or resistant to an infectious disease through the administration of a vaccine. Vaccines stimulate the immune system to protect the person against subsequent infection or disease. Immunisation and vaccination are often used interchangeably. Technically, vaccine refers to the material that is used for an immunisation.

Typically medicines are provided when someone is already sick, or has some symptoms of an illness. Vaccination is fairly unique in that it requires individuals to anticipate and act on the possibility of an illness in the future. In most instances, immunisation is provided to otherwise healthy individuals.

Infants and young children are the focus of many immunisation programs, as it is beneficial to to establish immunity early in life. Parents, or legal guardians of the infant or child, are required to provide consent for the administration of the vaccine. A majority of parents consent and comply with the recommended program of vaccinations for their child, however, some parents do not. This chapter will provide an overview of immunisation and the theoretical frameworks concerned with motivations around childhood immunisation. Research findings are also considered in order to highlight key aspects that appear to influence parents decisions to vaccinate, or not vaccinate, their child.

Active immunity and herd immunity

[edit | edit source]Vaccines stimulate the body's immune system to make antibodies and memory cells that provide long term protection against infection. This is sometimes referred to as 'active immunity'.

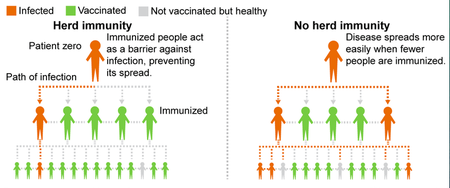

Along with protection for the individual, immunisation also decreases the number of people within the community who can be infected with the disease, this reduces the number of people who are exposed to the disease and the potential for the disease to spread.

Herd immunity occurs when a significant proportion of people within the population have been immunised, providing indirect protection to people who have not been immunised, including infants who are too young to be immunised, those with compromised immune systems, as well a those who have not responded to vaccination.

To establish herd immunity for any given vaccine preventable disease, a large number of people within the population must be vaccinated. Over time, high levels of immunisation will reduce the circulation of a disease and may ultimately lead to the elimination of the disease within that population. High rates of vaccination led to the elimination of small pox and eradication efforts continue for diseases such as polio and measles (Australian Academy of Science, 2016). Today, it is estimated that worldwide vaccination programs prevent between 2 to 3 million deaths through active and herd immunity (World Health Organisation, 2016).

History of immunisation

[edit | edit source]The Ancient Greeks recognised that people who had recovered from bubonic plague were resistant to getting the infection again. Survivors were used to nurse those who became ill during subsequent disease outbreaks.

British general practitioner Edward Jenner introduced the modern approach to vaccination in the late 18th century. His work was based on observations that milkmaids exposed to cow pox were also resistant to small pox. Edward Jenner developed a vaccine containing cow pox that was administered in order to promote immunity to small pox.

Controversy and concerns about vaccines have been around for almost as long as vaccines themselves. In 1904, President Rodrigues Alves approved a range of measures to improve hygiene in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Among the measures was forcible home entry to vaccinate inhabitants for small pox. During November 1904, public unrest developed in response to these measures, commonly referred to as the Vaccine Revolt. Thirty people were killed as a result of the civil unrest and many more were injured or imprisoned. Eventually the government regained control and the mandatory vaccination program continued. Small pox was eventually eradicated from the city.

Today, many countries have measures that seek to mandate immunisation. It can be a requirement for school entry or employment. Often a contentious objection to immunisation on philosophical or religious grounds can provide an exemption to these otherwise mandatory programs. Exemptions are also issued on medical grounds.

Childhood vaccination schedules

[edit | edit source]A wide range of vaccines are currently available, and almost as many are under development. To establish sufficient immunity, some vaccines need to be administered more than once. Combinations of vaccines can also be administered in one dose. Many governments recommend a schedule of vaccinations that start shortly after birth. Immunisation prevents illness and disability so it is very cost effective for governments. Recognising this, many countries provide access to the recommended vaccines at no or low cost.

The World Health Organisation's Recommended routine immunisations for children, September 2016

Adverse events following immunisation

[edit | edit source]Similar to all medicines, vaccinations are not without risk of undesirable side effects. These side effects are referred to as Adverse Events Following Immunisation (AEFI).

An analysis of Australia's AEFI surveillance data found 8.4 AEFI's per 100,000 vaccinations doses. Fifty-three percent of the AEFI were deemed to be non-serious, including injection site reactions, fever and rash. Seven percent of the AEFI fell into the more serious category, requiring hospitalisation. This group of AEFI included convulsions, anaphylactic reactions and intussusception. Two deaths were recorded and investigated. No clear causal relationship was established between the administration of the vaccination and the subsequent cause of death (Mahajan, Dey, Cook, Harvey, Menzies & Maccartney, 2012). This illustrates that AEFI data captures a range of health events which may be coincidental to vaccination, rather than causal.

Immunisation and motivation theory

[edit | edit source]

When considering the motivational framework that motivates parents to vaccinate, or not vaccinate their children, a number of theories provide useful insights into the decision making process.

Health belief model

[edit | edit source]Becker's Health belief model seeks to explain and predict whether or not an individual engages in a particular health behaviour, based on the perceived benefits and barriers, self efficacy and the presence of a stimulus to trigger the desired behaviour.

- Perceived severity is the subjective assessment of the severity of particular health problem and its consequences. For immunisation this includes the perceived severity of the disease and any potential longer term complications .

- Perceived susceptibility is the perception of how susceptible a person is to the health problem or disease. Infants and children are often considered to be more vulnerable to particular diseases, due to immature immune systems.

- Perceived benefits refers to the perceived benefit of the health behaviour. For immunisation this could include aspects like life long immunity for the child, as well as protection for younger siblings.

- Perceived barriers refers to obstacles that an individual may encounter when engaging in a health behaviour, and are often compared to the perceived benefits. Perceived barriers for immunisation include costs and access to health care professionals.

- Modifying variables includes demographic, psychosocial and structural variables unique to the individual that impacts on their perceptions. For immunisation this includes age and education level of parents, the influence of family and friend and health literacy. Modifying variables can directly and indirectly contribute to perceptions of seriousness, susceptibility as well as benefits and barriers.

- Cue to action is a cue or trigger that seeks to elect engagement in the health related behaviour. Cues can be internal and external, and can vary widely in strength. Reminders from health care professionals would constitute a cue to action for childhood immunisation.

- Self efficacy was not part of the original model, but was added in the 1980s in order to reflect the individual's perceptions of their ability to successfully perform the health behaviour. In relation to immunisation, self efficacy beliefs may account for the reason that some parents chose to delegate the immunisation appointment to the other parent or another family member.

Protection motivation theory

[edit | edit source]Protection motivation theory (PMT) was developed in 1975 and seeks to provide a social cognitive explanation of why people engage in protective behaviours. PMT suggests that individuals protect themselves based on four primary factors:

- Perceived severity of a threat

- Perceived probability of its occurrence

- Efficacy of the preventive behaviour, and

- Perceived self efficacy.

These four factors are further divided into two themes. Threat appraisal, which is the combination of perceived severity and probability of occurrence, as well as rewards, which are any positive aspects of engaging or continuing with unhealthy behaviour. For immunisation these factors would amount to considerations relating to the severity and prevalence of the disease being vaccinated against, as well as the effectiveness of the vaccine and the ability to access health care providers.

Theory of reasoned action/planned behaviour

[edit | edit source]The theory of reasoned action, developed by Fishbein and Ajzen in the 1960s, aims to explain the relationship between attitudes and behaviours within human action. The theory can be used to predict how people will behave based on the outcomes they expect will come as a result of engaging in the behaviour. In this model, behavioural intentions are a joint function of the individual's attitudes and subjective norms. Subjective norms constitute the perception of the behaviour expected by significant others.

The theory of planned behaviour extends the theory of reasoned action through the additional concept of perceived behavioural control, which is linked to both behavioural intention and the likelihood of engaging in the behaviour. In relation to immunisation, this model accounts for aspects such as the expected immunity that comes as a result of immunisation, and the attitudes to immunisation that are conveyed by friends and family members, as well as accessing health care professionals and the vaccination itself.

Cultural theory of risk

[edit | edit source]The cultural theory of risk suggests that individuals attend to risks and related information in a way that reflects and reinforces their preferences about how society should be organised or 'cultural worldview'. Along with these views, the theory suggests that people attend to, and place significance on, instances of misfortune that are consistent with these views. This occurs under the context of biased assimilation, polarisation and credibility heuristics. Under this model, the same information can generate different perceptions of risk, depending on the individual's view and subsequent interpretation of the information. Research supporting this model's application around fears associated with HPV vaccination confirms that participants place more credibility in spokespeople who aligned with their worldview, and this also influenced their perception of risk relating to the vaccination (Kahan, Braman, Cohen, Gastil & Slovic, 2010).

Reactance Theory

[edit | edit source]Reactance theory, developed by Brehms in 1966, is concerned with an unpleasant motivational state that emerges when a person encounters a real or perceived threat to their freedom, or autonomy. This unpleasant motivational state results in behavioural and cognitive efforts to re-establish freedom, and is accompanied by the experience of strong emotions. Reactance theory acknowledges that individuals who feel pressured into changing their behaviour may become more resistant to change. Programs that mandate vaccination may increase the likelihood of reactance responses. If parents perceive that their freedom to make medical decisions on behalf of their child is being undermined, they may be more inclined to protest against this interference and not vaccinate their child. Reactance theory provides a useful insight into why some parents do not vaccinate their children, despite strong influences to do so.

Extrinsic motivation and reinforcement

[edit | edit source]Many parents have a strong internal or intrinsic desire to immunise their children. Other parents rely on the environment to provide them with cues on whether or not to immunise their child. In these instances, extrinsic motivation plays a role in determining vaccination decisions. Reinforcement is a basic principle of operant behaviour that suggests consequences have an effect on behaviour. Reinforcement has been applied to a wide range of social and health issues. Positive reinforcers seek to increase the probability of the desired behaviour. In the area of immunisation, reinforcements include approaches that make enrolment in school and child care contingent on vaccination.

Parental positions on vaccination according to attitudes and behaviours

[edit | edit source]The theoretical models provide insights in how and why parents make vaccination decisions. It is important to also consider the actual proportion of parents who do decide to vaccinate their children, and those parents who do not. Leask, Kinnersley, Jackson, Cheater, Bedford and Rowles (2012) propose the following breakdown of parent attitudes and behaviours around decisions to vaccinate.

Table 1. Characteristics, attitudes, and behaviours of parental positions on child vaccination

| Category | Characteristics, attitudes and behaviours |

| Unquestioning acceptor

30-40% |

Parents in this category vaccinate or intend to vaccinate their child and do not question the necessity or safety of vaccines. These parents often have a good relationship with a health care professional. This group tends to have less detailed knowledge about vaccination. |

| Cautious acceptor

25-35% |

Parents that fall into this category vaccinate their child despite having minor concerns about vaccine safety. |

| Vaccine hesitant

20-30% |

Parents in this category vaccinate their child but report more significant concerns. They question the safety and social benefits of vaccination. These parents focus on risks associated with vaccination, and are more aware of AEFI. These parents may also be aware of or associate with other parents who have chosen not to vaccinate their child. These parents are more likely to discuss the risks of vaccination with a health care professional. |

| Late or selective vaccinator

20-27% |

Concerns about vaccination result in this group of parents choosing to delay vaccination or to vaccinate selectively. These parents often report concerns about the number of vaccines children are required to receive and have conflicting feelings about who they can trust to answer their vaccination questions. This group tends to have the highest level of knowledge about vaccination. |

| Vaccine refuser

<2% |

Parents in this category refuse all vaccines for their child. These parents may have a philosophical or religious objection to vaccination. Some of these parents report negative experiences with the health care system. These parents are more likely to receive their healthcare from alternative health professionals. It has also been observed that these parents tend to cluster in communities where their views or beliefs are more likely to be shared. |

This categorisation of parental attitudes and behaviours on vaccination is consistent with earlier findings (Angelmar & Morgon, 2012). An important aspect of this categorisation is that a large majority of parents vaccinate, even though some have concerns. It is only a very small group of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children. Over time parents may move into different categories.

|

Case study

Kristen O'Meara wrote about an experience that changed her views on vaccination. Kristen is a special needs teacher who decided not to vaccinate her first child in 2010, following concerns that had arisen while she researched the topic. She reports that she was quickly consumed in the anti vaccination culture, and thought parents who did vaccinate were "just sheep following the herd". In 2015, all three of Kirsten's children fell ill with rotavirus, as did she and her husband. Not long after this experience Kirsten decided to do further research on immunisation. This time she came to a different conclusion, and has decided to vaccinate her children. Today she shares her story in the hope that it makes other parents reconsider their anti vaccination stance. |

What motivates parents to immunise their children?

[edit | edit source]

No single motivational theory completely explains or predicts whether parents will immunise their child. However there are some consistent factors in the models that are also highlighted in vaccination research.

Fear of vaccine preventable disease

[edit | edit source]Fear of vaccine preventable disease appears to be a major contributor to a parents decision to immunise their child. Research highlights that parents who vaccinate consistently voice concerns that exposure to vaccine preventable disease results in life-long disability or death (Manthiram, Edwards & Hassan, 2014). The higher the perceived severity of the disease, the higher the reported intention to vaccinate (Thomson, Robinson, Valle-Tourangea, 2015).

Health care professionals

[edit | edit source]A consistent finding in vaccination research is that confidence in health care professionals is a significant determinant of a parent's decision to vaccinate. Parents rate their children's doctor as their most trusted source of vaccine information (Nyhan, Reifler, Richey & Feed, 2014). This is particularly important for parents who are undecided about vaccination. While many parents do make the decision to vaccinate their child prior to an encounter with a health care professional, at least one fifth do not (McGuire, 1997). Further, research shows a consistent positive correlation between a health care professional's recommendation to vaccinate and subsequent vaccination (Manthiram, Edwards & Hassan, 2014). Even for parents who are hesitant to vaccinate, a positive encounter with a health care professional increases the likelihood of vaccination (Leask, et al., 2012).

Incentives and reinforcement

[edit | edit source]Parents often have very busy schedules, balancing work, caring for the family and other commitments. Utilising incentives and reinforcements aims to provide additional motivation for parents to overcome any perceived barriers to vaccination. Research shows that incentive payments, for one off and multiple vaccinations, can increase vaccination by up to 10 percent (Mantzari, Vogt & Marteau, 2015). Linking immunisation to enrolment in school and child care is also effective (Ward, Chow, King & Leask, 2012).

Reinforcement also appears to work since its introduction in Australia at the start of this year (2016), the No Jab No Pay policy has resulted in 5,700 children who were previously not vaccinated to being vaccinated, and a further 148,000 children who were partially immunised to being fully immunised (Commonwealth Department of Health, 2016). Under this measure, parents who do not vaccinate may forfeit up to $15,000 AUD in government support payments for not vaccinating their children according to the recommended schedule.

What motivates parents to not immunise their children?

[edit | edit source]

Vaccine hesitancy versus vaccine resistance

[edit | edit source]It is important to reiterate the distinction between vaccine hesitant parents and those who are resistant to vaccination. The motivations associated with these instances are likely to be very different. Thomas, Robinson and Valle-Tourangeau (2016) highlight that reasons for vaccine hesitancy are largely due to safety concerns. These parents may be inclined to vaccinate selectively or delay until the child is older. Vaccine resistant parents have no desire or intention to vaccinate their children.

Concerns about vaccine safety

[edit | edit source]Safety concerns associated with vaccines is clearly one of the most significant factors for non-vaccinating parents (Thomson, Robinson & Valle-Tourangeau, 2015). Parents who do not vaccinate their children often report that they consider the vaccines to be more harmful than the disease itself (Serpell & Green, 2006). Non-vaccinating parents report concerns about AEFI, vaccine ingredients, the number of immunisations and the possibility that vaccination could expose their child to a disease (Niederhauser & Markowitz, 2007). Betsch and Sachse (2013) found that failure to acknowledge the risk of AEFI, or dismiss parental concerns, further undermines their confidence. Parents who are vaccine hesitant or resistant are particularly sensitive to vaccine information that they perceive to be inconsistent or ambiguous (Serpell & Green, 2006). Due to confirmation bias which is the preference to discount evidence that is contrary to current views, attempts to influence anti vaccination attitudes are often unsuccessful, and may actually strengthen their stance (Horne, Powell, Hummel, Holyoak, 2015).

Pain

[edit | edit source]Needle fear is common among children and adults, and children have reported that having a needle is one of their most feared and painful experiences (McMurtry, 2013). The Australian Immunisation Schedule currently recommends 16 separate vaccinations or needles for children from birth to four years of age. Up to three vaccinations, or needles, can be administered in a single vaccination appointment. Research has shown that the perceived trauma of immunisation is one reason why some parents chose not to immunise (Neiderhauser & Markowitz, 2007). Along with the increased use of combination vaccines, current research is also focusing on new approaches to childhood immunisation that are needle-free, including edible plant based vaccines, nasal sprays, needle free skin patches and micro-needles that allow children to be immunised without discomfort (Australian Academy of Science, 2016).

Lack of trust in government and vaccine producers

[edit | edit source]Non-vaccinating parents report lower levels of trust in the government and the pharmaceutical industry. Research has shown that engaging parents who are suspicious of government and the pharmaceutical industry in discussions about the scientific evidence in support of vaccination is unlikely to change their decision, and often reinforces their stance (Manthiram, Edwards and Hassin, 2014).

'Free riding' herd immunity

[edit | edit source]The concept of herd immunity may lead some parents to believe that high levels of immunisation within the community protect their child from exposure to the disease, reducing the need to vaccinate. This is referred to as 'free-riding'. Research with parents has shown that 'free-riding' does factor in decisions not to vaccinate (Serpell & Green, 2006). Further, health messages that seek to promote immunisation, but do not highlight the social benefits of immunisation, have been found to inadvertently increase the likelihood that people consider the possibility of 'free-riding', rather than vaccinating (Betsh, Bohm and Korn, 2013).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Motivational theories provide a useful framework for considering what motivates parents to vaccinate or not vaccinate their children. The most prominent feature highlighted in the vaccination research appears to be the perception of risk, risk of the vaccine preventable disease, or the risks associated with vaccination itself and AEFI. This perception of risk confirms that parents make vaccination decisions with their children's best interest at heart, but they may interpret information on the safety and risks associated with vaccination differently. Other attitudes and experiences also exert influence on decisions to vaccinate. While the research confirms that the majority of parents do decide to vaccinate their children, and the benefits of doing so extend from the individual to the broader community, a small but persistent group of parents decide not to vaccinate. This group appears to be fairly resistant to intervention, in fact intervention may inadvertently strengthen their opposition to vaccination.

Some researchers suggest that efforts to increase childhood immunisation should prioritise vaccine hesitant parents over those who are resistant. Positive encounters with healthcare professionals, reinforcement and incentives and credible information may influence vaccine hesitant parents to ultimately decide to vaccinate their children. Given the community benefits of high immunisation rates, and the potential to eradicate disease, research that further capitalises on motivational theories, preventive health behaviours ad how they influence parents decisions to vaccinate, is warranted.

References

[edit | edit source]Angelmar, R., & Morgon, P. A. (2012). Vaccine marketing. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn/1991709

Betsch, C., Korn, L., & Holtman, C. (2015). Don't try to convert the anti vaccinators, instead target the fence-sitters. PNAS, 112(49): 6725-6726.

Betsch, C., & Sache, K. (2013). Debunking vaccination myths: Strong risk negations can increase perceived vaccination risks. Health Psychology, 32(2): 146-155.

Buttenheim, A, M., Cherg, S. T., & Asch, D. A. (2013). Provider dismissal policies and clustering of vaccine-hesitant families: An agent-based modelling approach. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8): 1819-1824.

Cawley, J., Hull, H. F., & Rousculp, M. D. (2010). Strategies for implementing school-located influenza vaccination of children: A systematic literature review. Journal of School Health, 80(4): 167- 175.

Falomir-Pichastor, J M., Toscani, L., & Despointes, S. H. (2009). Determinants of flu vaccination among nurses: The effects of group identification and professional responsibility. Applied Psychology, 58 (1): 42-58. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00381.x

Gerend, M. A., & Shepherd, J. E. (2012). Predicting human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in young adult women: Comparing the Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Ann Behav Med, 42(2): 171-180. dii:10.1007/s12160-012-9366-5.

Horne, Z., Powell, D., Hummel, J. E., & Holyoak, K. J. (2015). Countering antivaccination attitudes. PNAS, 112 (33): 10321-10324.

Leask, J., Kinnersley, P., Jackson, C., Cheater, F., Bedford, H., & Rowles, G. (2012). Communicating with parents about vaccination: A framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics, 12, 154-165.

Mahajan, D., Dey, A., Cook, J., Harvey, B., Menzies, R. I., & Maccartney, K. K. (2012). Survelliance of adverse events following immunisation in Australia, 2012. Annual report. CDI, 38(3): 232-246.

Manthiram, K., Edwards, K., & Hassan, A. (2014). Sustaining motivation to immunize: Exchanging lessons between India and the United States. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 10(10): 2930-2934.

Mantzari, E., Vogt, F., & Marteau, T. M. (2015). Financial incentives for increasing uptake of HPV vaccinations: A randomised control trial. Health Psychology, 34(2): 160-171.

McGuire, C. (1997). Childhood immunisation: The parental perspective. Children & Society, 11:264-267.

McMurtry, C. M. (2013). Pediatric needle procedures: Parent-child interactions, child fear and evidence-based treatment. Canadian Psychology, 54(1): 75-79. doi:10.1037/a0031206

Niederhauser, V. P., & Markowitz, M. (2007). Barriers to immunizations: Multiethnic parents of under- and unimmunized children speak. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 19: 15-23. dii:10.1111/j.17457599.2006.00185.x

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Richey, S., & Freed, G. L. (2014). Effective messages in vaccine promotion: A randomized trial. Pediatrics, 133(4): 835-842.

Serpell, L., & Green, J. (2006). Parental decision-making in childhood vaccination. Vaccine, 9-10.

Silverman, K., Jarvis, B. P., Jessel, J., & Lopez, A. A. (2016). Incentives and motivation. Pediatrics, 130 (3): 522-530.Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 2(2): 97-100.

Thomson, A., Robinson, K., & Valle-Tourangeau, G. (2016). The 5As: A practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine, 34, 1018-1024.

Ward, K., Chow, M. Y., King, C., & Leask, J. (2012). Strategies to improve vaccination uptake in Australia, a systematic review of types and effectiveness. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36(4): 369-377.