User:Jenny O/Prosocial Behaviour

What is prosocial behaviour?[edit | edit source]

Prosocial behaviour generally refers to those acts designed to benefit another person or group (e.g., sharing, helping, acts of kindness). It is the antithesis to anti-social behaviour. It involves prosocial intent and behaviour, not the intent alone.

The benefits of this behaviour are contextually dependent. Fiske (2004) provides examples such as circumcision, foot binding, piercing and scarring as being prosocial actions in certain contexts. Similarly, behaviours such as conformity and obedience can be prosocial or anti-social, depending on the context.

People engage in prosocial behaviour for reasons of self-interest, social status, reciprocity, conformity (e.g, being fair), abiding by rules (Rule of law), altruism, reward, convenience, or guilt. Indeed humans are cultural animals who have a full sense of fairness and object to being under-benefited (resulting in anger or resentment) or over-benefited (resulting in guilt). Survivor guilt is one such reaction [i.e., a reaction of guilt to over-benefiting (surviving)]. Unfortunately, humans also tend to have is a selfish impulse against social conscious. Sharing and conserving resources requires people to resist this desire. Fortunately, this process develops with maturity and socialisation, or as people embrace communal values.

Cooperation, forgiveness, obedience and conformity[edit | edit source]

Cooperation, forgiveness, obedience and conformity can all play a role in prosocial behaviour.

Cooperation is a simple form of prosocial behaviour based on reciprocity, by working together each person is able to reach a common goal. The Prisoner’s Dilemma has been used to assess cooperation. This is an example of game theory where the outcome for one player is dependent on the action of the other player. The players are forced to choose between cooperation or competition. Cooperation is fragile and easily destroyed: if players want to cooperate there is mutual benefit, if they choose to compete, difficulty ensues (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008).

Forgiveness is an interesting concept. It is defined as ceasing to feel anger or resentment, or the desire to seek retribution from someone who has wronged you (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008). Most importantly, it does not equate with exoneration. Forgiveness is prosocial as it offsets a bad deed and releases the person from his or her obligation. However, it will not necessarily stop the person from re-offending. Nevertheless, forgiveness has benefits for the relationship and health of the forgiver and the wrongdoer. I have never thought much about forgiveness and what it really means. It now makes some sense particularly in light of the following: Many years ago I heard a man talk at a seminar about his need to forgive the murderer of this two daughters. This man had (understandably) made it his life’s mission to help others to cope with trauma. The underlying premise of his work was the need for forgiveness and he spoke at length about how he came to forgive his daughters’ murderer, even going to visit the perpetrator in gaol to tell him he was forgiven. Only after he had done this could he start to come to terms with the death of his children.

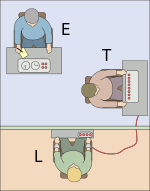

Obedience refers to subordinate action in accordance with the orders of an authority figure (Lecture 8). Obedience can be prosocial, particularly in groups, organisations, sporting teams, or in military life. However, blindly following orders or abuse of obedience can be detrimental to psychological well-being and social order (As demonstrated in Nazi Germany). The classic experiments of Milgram examined the willingness of participants (ordinary people) to obey an authority figure’s orders to administer electric shocks to another person (a confederate) under the instruction of an experimenter (a researcher in a white coat). I wonder whether Milgram was in fact measuring obedience or other social psychological constructs. Nevertheless, Milgram found 62.5% of participants delivered severe shocks even when they believed it harmed the person. Milgram’s experiments were most controversial for ethical and moral reasons but highlighted how effortlessly people blindly follow authority.

Also see a simple example of this process at: Milgram Experiment 2007.

Conformity is going along with the crowd (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p.266), and may be good or bad depending on the context. People are more likely to conform when they are being watched. People may outwardly conform while privatley believing something else (i.e, public conformity). Normative social influence is conforming to the expectations of others, specifically to be like or accepted (Demonstrated in the experiments of Asch - I also wonder if he was actually measuring conformity or some other constructs). Informational social influence refers to going along with the crowd because you think they know more. (Conformity and the Asch experiments are also covered in Social Thinking: Social influence and persuasion).

Why do people help others?[edit | edit source]

People help others for a range of reasons. From an evolutionary perspective, animals have an innate tendency toward helping others. There is also a tendency to help our kin (kin selection) This is strengthened in life and death situations (e.g., a father who is a poor swimmer rescuing his son from drowning in the surf).

According to Batson (1994) people can be motivated to help through:

Egoism: For one’s own benefit – the helper wants something in return or wants to escape punishment

Altruism: For the benefit of others – the helper seeks nothing in return

Collectivism: For the benefit of one’s group

Principalism: For moral reasons

The empathy-altruism hypothesis proposes that altruism is based on empathy (identifying with the emotions of others). The textbook reports on a study by Batson et al. (1981) who tested this hypothesis. They found a relationship between a person’s level of empathy and his or her ability to escape in a helping situation. Those high in empathy would help regardless of the ability to escape. Those low in empathy were more likely to help only if they could not escape. Thus, someone low in empathy will opt to reduce personal distress by escaping the situation. An alternative view, presented in the Negative state relief theory, proposes that people help to relieve their own distress (Lecture 8).

Thus, altruism is seen as self-sacrificing and not involving obvious reward. An altruistic helper seeks nothing in return and is motivated by the need of others, often at a personal cost. The website Prosocial Behaviour uses the example of an anonymous donation as a prosocial act with altruistic intent. In my mind this seems to illustrate the concept quite well. Nevertheless, there is some debate as to whether true altruism can exist (Also see Social Psychology: My essay, 2007).

This lecture led me to re-think the possible motives of the foreigners who remained in Rwanda to help others during the genocide (see Ghosts of Rwanda). It is possible that these people stayed to help to alleviate their own distress (Negative state of relief theory), rather than the distress of others. However, I still have some faith in mankind and would still like to believe that these humans were indeed altruistic in their actions. I also believe that these people probably have innate (albeit rare) qualities that initially lead them to work in these unique helping roles, and consequently facilitated their altruistic behaviour.

The textbook and lecture also outlined other factors attributed to helping behaviours. These include: personality (although a weak predicator), helper competence, attributions (e.g., people are less likely to help if they believe others are to blame for their own circumstances) or personal beliefs (e.g., self-concept/self-esteem, highly moral or religious beliefs). It is no surprise that females, those who are more attractive, kin or similar people and those seen as deserving are more likely to be helped by others. Interestingly, but maybe not surprisingly, men are more likely to help in emergency situations and women in more mundane circumstances.

Another interesting and reasonably well-known psychological phenomenon is the the bystander effect. Researchers have found that people are less likely to help when in the presence of others, than they would if they were alone. Examples of people being ignored by passers by as they bled to death, or have been assaulted and left to die on a footpath, are often used to illustrate this point. Apparently people assume others are helping or are more qualified to help. A state of pluralistic ignorance arises (i.e., individuals look to other group members for behavioural cues, when in fact the other group members are behaving in the same way). This results in a state of collective misinterpretation (Lecture 8). Another reason why people do not help is diffusion of responsibility or the feeling that one is not responsible due to the presence of others, which leads to social loafing in these circumstances.

Thus it seems that some humans are ready and willing to help others, while a number remain reluctant to do so (Mainly due to uncertainty). These barriers to helping can be reduced through education, awareness and socialisation.