Finding Common Ground

— Aligning concepts with reality.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Although we all live in the same world and share a single reality, we often seem to be worlds apart when discussing important issues. What is going on? How can we find common ground?[2]

Objectives[edit | edit source]

| Completion status: this resource is considered to be complete. |

| Attribution: User lbeaumont created this resource and is actively using it. Please coordinate future development with this user if possible. |

The objectives of this course are to:

- Understand the nature of reality.

- Identify the many layers of abstraction through which we encounter reality.

- Navigate through these layers of abstraction.

- Diagnose reasons for conflict during discussions.

- Find common ground.

This course is part of the Applied Wisdom curriculum, the Clear Thinking curriculum, and the Coming Together curriculum.

Slides based on this course are available, along with a video presentation of those slides.

If you wish to contact the instructor, please click here to send me an email or leave a comment or question on the discussion page.

Importance[edit | edit source]

Finding common ground is an important skill because it is useful for resolving the social, cultural, political, and economic polarization that is prevalent. Religious conflicts, international conflicts, nationalism, class struggles, racial tensions, culture wars, ideological conflicts, gender inequality, political polarization, book banning, hate crimes, climate change denial, and conspiracy theories are a few examples of the conflicts that are dividing people throughout the world.

When we can recognize that reality is our common ground, we can restore the civility that is essential to peaceful coexistence.

In a Nutshell[edit | edit source]

Here is a brief introduction to the key concepts presented in this course. The diagram can help you organize, recall, share, and apply these ideas.

- Reality exists and we all share in a single objective reality.

- There are several reasons why this fact is difficult for us to grasp and hold onto.

- Reality is vast, complex, and dynamic. Each of us directly encounters only a tiny slice of reality. We each experience only a glimpse of our vast universe.

- Our direct contact with reality is through our perceptions, which introduce omissions, distortions, and additions.

- Although we use words and other symbols to represent reality as we perceive it, these symbols are limited, and they only provide approximate representations of our perceptions.

- Because much of what we encounter is ambiguous, it invites us to interpret the information to resolve the ambiguity and provide us the comfort of certainty. Many cognitive biases influence our interpretations.

- We love telling and retelling stories. We easily substitute alluring stories for the complexities and difficulties of reality.

- Ideologies substitute a simplified belief system for the complexities of reality. We are easily attracted to these easy to use explanations.

- We can see beyond these illusions and better comprehend reality.

- Reality is our common ground. We can each find that common ground by advancing toward the center of the diagram shown above.

- Although these ideas are simply stated, they are difficult to fully grasp and put into practice. Please complete the remainder of this course and use these insights every day.

- We can find common ground.

Reality[edit | edit source]

For many practical reasons, this course begins with the assumption that reality exists. Everyday experience provides evidence that reality exists. Every time you decide to open the door before passing through the doorway, you are betting that reality exists. If you have lost your keys, then opening the door, or starting your car can become a real problem. If you have difficulty levitating, leaping tall buildings in a single bound, seeing through brick walls, teleporting, or time travelling, perhaps it is because you are encountering constraints imposed by reality.

Despite empirical evidence, people often argue against the existence of reality. In these arguments people may cite the allegory of the cave, the brain in a vat, the simulation hypothesis, the Matrix movies, claims that perception is reality, and postmodern theories.

While these are fascinating thought experiments that do deserve some serious philosophical investigation, they don’t provide much help in getting through our daily lives. I bet that reality exists.[3]

For the remainder of the course, we proceed with the assumption that reality exists.

Reality is vast, complex, and dynamic. Humans have only investigated a small portion of the universe, and our investigation is incomplete. Our awareness, observations, and perceptions of reality are neither complete nor accurate representations of reality. We do not observe the many cosmic rays passing through us each second, the atoms that make up the materials we encounter, billions of galaxies beyond the limits of our vision, the ultrasonic chirps used by bats to navigate, viruses, DNA, antibodies, greenhouse gasses, particulate contaminants, and much more of reality as it is.

This course makes the further assumption that we all live in the same universe[4]. All life forms discovered so far live together on our single planet, circling our sun, in our humble place in the universe. The universe is vast, yet it is all one world, and we all live together on this one planet we call Earth. All that we know of and all that we have ever experienced follow the same laws of physics. Remarkably, the entire world as we know it has emerged from a few fundamental building blocks.

Because we all live in the same universe, our reliable understanding of that universe must eventually converge toward one coherent description. Each phenomenon we observe must fit into a single coherent and integrated description of our universe. Either the description must evolve to accommodate each new observation, or our understanding of that observation must be interpreted consistently with that unified representation.

Building on these assumptions, it follows that reality is our common ground, even though any number of worldviews is possible. It is likely that each of us hold a worldview that is somewhat different from others. Of all the possible worldviews, one worldview is especially important. That is the worldview that corresponds to reality as closely as our best current understanding of reality allows. Because reality exists, we can examine reality, and we can align our worldview with reality. Because we all live in one world, reality is our common ground.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Complete the Wikiversity course on Facing Facts.

- Read the essay Perceptions are personal.

- Investigate further any of the arguments that appeal to you, listed above, that reality does not exist.

- If you can accept the assumption that reality exists, please proceed with the remainder of this assignment.

- Estimate what fraction of reality you are familiar with.

- Read the essay, Being 99.9% Ignorant.

- How many countries are there in the world? How many have you visited?

- Study modern research on the number of galaxies in the universe. How many have you visited?

- Scan this list of lists of unsolved problems. What fraction of reality has been investigated by humans?

- Can you accept the premise that reality exists far beyond our perceptions, investigations, and conceptions of it?

- Read the essay Reality is the Ultimate Reference Standard.

- Read the essay One World.

- Read the essay Reality is our common ground.

- Read the essay Aligning Worldviews.

- Optionally read the essay What there is. Consider writing your own such essay.

- Can you accept the premise that reality exists, we live in one world, we share one reality, and that reality is our common ground? If so, please proceed with the remainder of this course.

Perception[edit | edit source]

Perception transforms sensory information originating with some material object, known as the target or the distal stimulus into mental representations known as percepts, which do not exist elsewhere in the world.

Perception—the process of extracting information from energy that impinges on our sensory organs—is not straightforward. There is more to perception than meets the eye.[5]

Indirect theories of perception describe it as a constructive process that involves inference, learning, and experience.[6]

While it may seem reasonable that an ideal perception system would duplicate the observed target object exactly in the mental percept, this is not what happens. One theory hypothesizes that the purpose of perception is to allow organisms to locate and use affordances—what the environment offers the individual—for practical benefit.

Our most direct encounters with reality are through direct sensory observations and awareness. However, our perceptions are not exact replicas of the distal objects being perceived. Omissions, distortions, and additions take place. Fortunately, we can augment our direct perceptions to obtain a more accurate understanding of our world.

Omissions[edit | edit source]

Our direct perception accounts for only a tiny fraction of reality.

We can only directly perceive stimuli that our senses are exposed to, and our senses encounter only a small fraction of reality. We do not see what is behind us, the places we do not visit, and stimuli that are outside the range of our sensory systems. Attention is selective and of all we are exposed to, we are most likely to perceive only what our attention is drawn to and remain unaware of the rest. When our attention is drawn to moving objects, shiny objects, and unexpected occurrences we may be distracted from sensing other information in our environment.

The spectrum of light visible to humans is only a tiny fraction of the electromagnetic spectrum. Radio waves, microwave radiation, infrared radiation, visible light, ultraviolet radiation, x-rays, and gamma radiation are all electromagnetic waves of various wavelengths. These various forms of radiation span wavelengths ranging from as small as 10-11 meters (0.1 Å) to as long as 1,000 meters, however only light in the range of 400 nm – 700 nm (4x10-7 to 7x10-7 meters) is visible to humans. We have no way to directly sense radio waves, infrared and ultraviolet light, x-rays, and other forms of radiation. Humans are also unable to directly sense magnetic fields.

The range of human hearing is approximately 20 to 20,000 Hz, while dogs can hear sounds frequencies as high as 45 kHz and bats can hear frequencies as high as 200 kHz. Elephants can hear sounds at 14–16 Hz, while some whales can hear infrasound as low as 7 Hz.

It is estimated that dogs, in general, have an olfactory sense (sense of smell) approximately ten thousand to a hundred thousand times more acute than a human's.

Also, we are often unaware of what could be most obvious.

Not only does our direct perception account for only a tiny fraction of reality, much of what we do perceive is distorted.

Distortions:[edit | edit source]

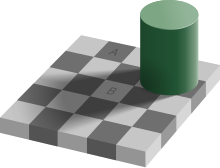

Distortions of the senses are called illusions. Although illusions distort our perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people. Illusions may occur with any of the human senses, but visual illusions (optical illusions) are the best-known and understood.

In the checker shadow illusion, shown here, two identically colored squares labeled “A” and “B” appear to be very different shades of gray. Reality as we perceive it may not be reality as it is.

In the Fraser spiral illusion, shown here, the overlapping black arc segments appear to form a spiral; however, the arcs are a series of concentric circles.

In addition to illusions, many images are ambiguous. As an example, please observe, and then interpret the image shown here.

What do you see? What else do you see? How certain are you of your conclusion? What do you have at stake in defending your interpretation?

Most people will see either a rabbit or a duck. If you see a rabbit, look again, and try to see a duck. Similarly, if you see a duck, look again, and try to see a rabbit.

This image, called the rabbit-duck illusion is inherently ambiguous. Someone who interprets it as representing a duck has as valid a claim to accuracy as someone who interprets this as representing a rabbit. In fact, it is neither and both. It is an ambiguous image open to at least two different yet equally valid interpretations. Similarly, a glass that is half empty is also half full.

In addition to optical illusions, we are susceptible to illusions that distort each of our senses. These include auditory, tactile, temporal, and intersensory illusions.

Magicians are performing artists who use illusions to entertain us. Charlatans, including fakes, mystics, counterfeiters, quacks, conspiracy theorists, and con artists, use illusions to deceive, cheat, and swindle us. Ideologs exploit illusions to promote their cause, special effects are often used in films and other artistic media to entertain us, and recently deepfakes are used to deceive us.

In addition to our perceptions being distorted, we also sometimes perceive things which are not there.

Additions:[edit | edit source]

Our perception systems create percepts that do not otherwise exist in the world. Examples include color perception, illusory contours and other patterns studied within Gestalt psychology, illusory pattern recognition, pain, phantom limbs, hallucinations, and distortions that occur during various altered states of consciousness. Our conceptions also influence our perceptions.

Humans perceive the color red when we look at light with a wavelength between approximately 625 and 740 nanometers. Note that although electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of approximately 700nm does exist in objective reality independent of the direct perception of any human, the percept we call red only exists in our minds as a construct of the perceptual system. This is a consequence of our trichromatic color vision system, including our visual cortex and other brain regions. Because color only exists as a feature constructed by the visual perception of an observer it is a subjective experience. When I see red, I have a subjective experience called redness. However, philosopher John Locke proposed a thought experiment, called the inverted spectrum, where we imagine two people sharing their color vocabulary and discriminations, although the colors one sees—one's qualia—are systematically different from the colors the other person sees. For example, perhaps the color we call red creates within me the subjective experience that the color we call green generates within you. We do not know if the subjective experience I call redness is like the subjective experience you have when seeing red.[7] The nature of redness is further explored in a philosophical thought experiment known as the knowledge argument, or Mary’s room.

This image, called Kanizsa’s triangle, gives the impression of a bright white triangle, defined by a sharp illusory contour, occluding three black circles and a black-outlined triangle. Even knowing the bright white triangle does not exist, it is reliably constructed by our visual perception system. This is one example of many illusory contours that evoke the perception of an edge without a shading or color change across that edge. We see an edge where none exists. Gestalt psychology studies many such images where it appears that “The whole is more than the sum of its parts.”

Apophenia is the tendency to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated things. For example Gamblers may imagine that they see patterns in the numbers that appear in lotteries, card games, or roulette wheels, where no such patterns exist.

One form, called pareidolia, is the tendency for perception to impose a meaningful interpretation on a nebulous stimulus, usually visual, so that one sees an object, pattern, or meaning where there is none. People may mistakenly interpret an object, shape, or configuration with perceived "face-like" features as being a face. Many people claim to see the man in the moon. In this satellite photograph of a mesa in the Cydonia region of Mars, often called the "Face on Mars" has been cited as evidence of extraterrestrial habitation.

As another example, what we feel as pain is our perception of tissue damage. Consider our perception of a toothache. The damaged tooth stimulates nerve impulses in our somatosensory nervous system. The brain perceives various nerve impulses transmitted through these neural structures as the unpleasant sensory and emotional experience we call pain. Notice that the brain receives only a pattern of nerve impulses and then constructs the perception of pain from those nerve impulses. Although the damage is in the tooth the perception of pain is constructed in the brain.

A phantom limb is the sensation that an amputated or missing limb is still attached. Approximately 80 to 100% of individuals with an amputation experience sensations in their amputated limb. In phantom limb syndrome, there is sensory input indicating pain from a part of the body that no longer exists. This phenomenon is still not fully understood, but it is hypothesized that it is caused by activation of the somatosensory cortex. The perception of the absent limb is constructed by our nervous system.

As another example, tinnitus is the perception of sound when no corresponding external sound is present.

Our perceptions are often distorted when we are experiencing altered states of consciousness. This may occur from the influences of drugs—especially psychoactive drugs including hallucinogens and alcohol—fatigue, disease, hypoxia (as can occur from hypoventilation and other breath control practices), hallucinations, delirium, and various mental illnesses.

Our conceptions often influence our perceptions. Try this simple quiz:

What does F-O-L-K spell? (Please say the word out loud.)

What is the white of an egg called? (Please say the word out loud.)

(What color is the white of an egg?)

If you said “yolk”, as many people do, you were influenced by psychological priming. Priming is a phenomenon whereby exposure to one stimulus influences a response to a subsequent stimulus, without conscious guidance or intention. For example, in experiments the word nurse is recognized more quickly following the word doctor than following the word bread.

We may be unaware of priming effects that arise in our daily lives. In one study subjects were implicitly primed with words related to the stereotype of elderly people (example: Florida, forgetful, wrinkle). While the words did not explicitly mention speed or slowness, those who were primed with these words walked more slowly upon exiting the testing booth than those who were primed with neutral stimuli.

There is more to perception than meets the eye!

Assisted Perception—Compensating for the quirks[edit | edit source]

Fortunately, there are many methods we can use to overcome and compensate for the deficiencies, distortions, quirks, and other characteristics of our direct perception systems. Microscopes, telescopes, oscilloscopes, many other scientific instruments, recording devices, and reference standards allow us to extend the reach, scope, and accuracy of our observations. Multiple observers, vantage points, perspectives, and viewpoints allow us to gain a more complete and reliable examination of reality when we share and integrate information.

Applying the principle of consilience and thinking scientifically increase the reliability of our observations and can help us see beyond illusions.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Observe the moon in the sky some evening.

- Estimate the size (diameter) of the moon.

- Estimate the distance the moon is from you.

- Research the accepted values of these numbers and compare them to your direct observations. How closely does the perceived distance and size compare to the accepted values?

- Optionally repeat this for the sun, bright stars, and other distant terrestrial and celestial objects.

Perceptions are Personal[edit | edit source]

We often hear that “perception is reality” and that “everything is relative”, despite knowing that a shared reality exists, and reality is our common ground.

Perceptions are vivid. Seeing things from our own point of view is always easier, and first-hand experiences seem more real than understanding another's point of view can ever be. Our eyes, nose, taste buds, tactile sensors, and ears connect directly only to our brain. Only you experience first-hand the direct sensory input of the world; you, your self, is the observer. This raw sensory input is interpreted and gains meaning through your unique perceptions and past experiences. Furthermore, contemplation, desire, intent, pain, introspection, consciousness, and reflection are all private and solitary. This unique first-person experience creates a fundamental asymmetry that contributes to many of the other asymmetries that govern social interactions. It also contributes to the asymmetric character of egotism, narcissism, selfishness, greed, and the magnitude gap. We judge others based on behavior and we judge ourselves based on intent. Your own point of view, the way you see things, is unique. The golden rule and our empathy struggle to overcome this fundamental imbalance.

It is often a mistake to generalize our personal perceptions beyond our own experiences. Standing in a meadow we see a flat earth, yet sunrise, time zones, global travel, earth satellites, GPS navigation systems, images from space, and travel to the moon all assure us the earth is nearly spherical. Reality is vast, complex, and dynamic, and our perceptions are only a tiny glimpse of all there is to know about reality. Only a global perspective brings us uncensored reality.

Reality exists and provides us with matters of fact. The Eiffel tower is 300 meters tall. You may perceive that as too short; others may perceive that as too tall, and many perceive that as simply beautiful.

See beyond the illusion that what you see is all there is. Perceptions are personal, but reality is our common ground. Our unique first-person viewpoint creates a powerful asymmetry that requires deliberate effort to see beyond. Transcend your personal perceptions, investigate the vastness and complexity of reality from a global perspective, and embrace reality as our common ground.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Read the essay Perceptions are Personal.

- Reflect on occasions when you projected your own perceptions onto others or beyond your own experience.

- Recognize the limited scope and likely deficiencies of your perceptions.

Representation[edit | edit source]

At least until we become proficient at mental telepathy, we need some other way to represent our thoughts and to communicate our thoughts to others.

Words are one type of symbol used to represent reality. Other symbols might include sounds, gestures, facial expressions, icons, logos, drawings, models, analogies, metaphors, and other representations. The mapping from words to perceptions to reality is often imprecise. We may describe a certain color simply as red, without clarifying what shade of red we are describing. If I tell you I am sitting in a chair, you might imagine a rocking chair, a desk chair, or a recliner. Syntactic ambiguity often adds to the confusion.

Do not mistake the symbol for reality. The noumenal world exists independent of our senses and may differ from the phenomenal world we perceive and the symbols we use to represent it.

Language and other symbols can be constraining, ambiguous, refer to social constructs, prejudiced, based on artificial boundaries, or focus on convenient representation rather than reality. These features, distortions, and inaccuracies are explored further below.

Constraining Language[edit | edit source]

Consider the image on the right. What can we use it for? This wire form is commonly called a paper clip and is typically used to clip together sheets of paper. However, lateral thinkers have identified at least one hundred alternative uses[8] for this object. Observing the object, thinking expansively and creatively about what it might be, how it can be used, or what it might do, can identify many possibilities. This unclassified reality invites many potential uses. Once the object is named, an interpretation is imposed, and the object becomes restricted.

Naming the object assigns the object to one category, as it excludes others.

This table describes possibilities before and after it is interpreted, assigned to a category, and named.

| Encounter with reality: | Interpretation and Representation: |

|---|---|

|

|

Language and other symbols are ambiguous, persuasive, and subtle, and can be used heroically, precisely, expansively, restrictively, deceptively, and manipulatively. Here are some examples.

Ambiguous Language[edit | edit source]

Polysemy is the capacity for a sign (e.g., a symbol, a word, or a phrase) to have multiple related meanings. A word can have several word senses. As an example, the word bank can have at least these 7 distinct meanings:

- a financial institution

- the physical building where a financial institution offers services

- to deposit money or have an account in a bank (e.g., "I bank at the local credit union")

- a steep slope (as of a hill or the rising ground bordering water)

- to incline an airplane laterally

- a supply of something held in reserve: such as "banking" brownie points

- a synonym for 'rely upon' (e.g. "I'm your friend, you can bank on me").

Syntactic ambiguity is language where a sentence may be interpreted in more than one way due to ambiguous sentence structure. For example, the sentence John saw the man on the mountain with a telescope can have these various interpretations.

- John, using a telescope, saw a man on a mountain.

- John saw a man on a mountain which had a telescope on it.

- John saw a man on a mountain who had a telescope.

- John, on a mountain and using a telescope, saw a man.

- John, on a mountain, saw a man who had a telescope.

Combining polysemy with syntactic ambiguity results in multiplying the ambiguity. For example, Gerald Weinberg identifies dozens of interpretations of the sentence “Mary had a little lamb”[9] and then goes on to suggest 20 more techniques for identifying ambiguity in sentences.

Reifications are a class of nouns that do not refer to real objects but rather to abstract concepts. Examples include justice, freedom, liberty, equality, rights, duty, responsibility, truth, fairness, and citizen and extend to include concepts such as race, land ownership, owning coal, money, debt, contracts, and even agreement. These labels cannot be resolved to brute facts but are often treated as if they do. This results in a reification fallacy. A map is not the territory, an image of a pipe is not a pipe, and there is little or no agreement on what “justice” is.

Simple phrases such as “we seek justice”, “justice was served”, “liberty and justice for all”, “establish justice”, and “ours is a nation of laws” become very ambiguous, complex, and controversial when we recognize the wide range of meanings attributed to the abstract concept of “justice”.

The concept of justice differs in every culture. Early theories of justice were set out by the Ancient Greek philosophers Plato in his work The Republic, and Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics. Throughout history various theories have been established. Advocates of divine command theory argue that justice issues from God. In the 1600s, theorists like John Locke argued for the theory of natural law. Thinkers in the social contract tradition argued that justice is derived from the mutual agreement of everyone concerned. In the 1800s, utilitarian thinkers including John Stuart Mill argued that justice is what has the best consequences. Theories of distributive justice concern what is distributed, between whom assets or liabilities are to be distributed, and what is the proper distribution. Egalitarians argued that justice can only exist within the coordinates of equality. John Rawls used a social contract argument to show that justice, and especially distributive justice, is a form of fairness. Property rights theorists (like Robert Nozick) also take a consequentialist view of distributive justice and argue that property rights-based justice maximizes the overall wealth of an economic system. Theories of retributive justice are concerned with punishment for wrongdoing. Restorative justice (also sometimes called "reparative justice") is an approach to justice that focuses on the needs of victims and offenders.

There are many words to avoid when trying to be objective and precise.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Choose a speech or other text to use for this assignment. This may be chosen from this list of speeches, the Wikisource speeches portal, amendments to the United States Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, landmark court decisions, or any other source.

- Identify instances of ambiguous language in the chosen text.

- For at least three instances of ambiguous language, list various meanings that can be reasonably implied by the language used. For example, the ambiguous phrase “in the future” could mean seconds, hours, days, weeks, months, years, centuries, or eons from now.

- Suggest more precise and objective language that could be substituted for the language used.

- Suggest an operational definition to replace or clarify the ambiguous language.

Social Constructs[edit | edit source]

When we endow brute facts with additional status, we create social constructs.

Social constructs rely on collective human agreement, or at least acceptance of the imposition of the new status Y on the brute fact X.

Social constructs include games such as soccer, baseball, and chess. Bureaucracies including clubs, organizations, and corporations are social constructs. Titles such as chairman, president, king, and pope, along with governments, financial instruments, property ownership agreements, and religions are social constructs.

Social constructs are ambiguous, sometimes fragile, and often require referees of some form. The agreements used to form the social constructs may be obsolete or challenged. Social constructs can be mismatched to relevant brute facts.

Because social constructs are so common and so prominent, we can easily mistake them for brute facts. This is an error. Mistaking social constructs for brute facts introduces several layers of abstraction and creates distortions that distance us from realty.

As a result of ambiguity and defective agreements many social constructs are poorly aligned with the brute facts they are based on, and many mismatches occur. These cause friction in our society and can contribute to many challenges we face. By observing the mismatch of social constructs to brute facts and informed consent, we can begin to troubleshoot and improve the collection of social constructs that create our culture and institutions.

The bad news is that we face many issues resulting from social constructs misaligned with brute facts or based on defective agreements. The good news is that because social constructs are human constructs, we can work to improve them.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Choose a speech or other text to use for this assignment. This may be chosen from this list of speeches, the Wikisource speeches portal, amendments to the United States Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, landmark court decisions, or any other source.

- Identify instances of social constructs that appear in the chosen text.

- For at least three instances of the social constructs identified, list various meanings that can be reasonably implied by the language used. For example, the second amendment uses the term “Militia”. This could mean military unit, police units, paramilitary units, security guards, or individuals.

- Suggest more precise and objective language that could be substituted for the language used.

- Suggest an operational definition to replace or clarify the ambiguous language.

Prejudiced Language[edit | edit source]

Loaded language is rhetoric used to influence an audience by using words and phrases with strong connotations. This type of language is unclear (vague) and can be used to invoke an emotional response or exploit stereotypes. Loaded words and phrases have significant emotional implications and involve strongly positive or negative reactions beyond their literal meaning. These may include racists or sexist words, ethnic slurs, religious slurs, and other pejorative terms.

Examples of contentious labels include: cult, racist, perverted, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, misogynistic, sect, fundamentalist, heretic, extremist, denialist, terrorist, freedom fighter, bigot, myth, neo-Nazi, -gate, pseudo-, controversial, and others.

Beware of Boundaries[edit | edit source]

The sorites paradox poses the question, if removing one grain from a heap of sand leaves it a heap, then one grain of sand is also a heap. When does a heap of sand transform into a few grains of sand that are no longer a heap? This paradox illustrates that the concept of heap is ambiguous. Also, the boundary between a heap and some smaller collection is also ambiguous.

In conventional language, logic, mathematics, and decision-making, we generally regard boundaries as discrete or definitive limits or borders, which permanently and absolutely divide one thing or locality apart from other things or localities. For such definitive limits to exist, however, they would have to be so sharp as to have no thickness. By contrast, even when viewed from afar and over short durations, natural boundaries often appear diffuse, mobile, and impermanent, defying such precise, abstract definition. Naturally occurring boundaries are inherently ambiguous. Artificial boundaries are often sharply defined. This mismatch between how boundaries occur naturally and how we chose to represent them can lead to several problems.

Racial classifications create problems because they impose sharply defined boundaries where no natural boundary exists. Racial classifications are socially constructed. While partially based on physical similarities within groups, race does not have an inherent physical or biological meaning. Therefore, race assignment is inherently ambiguous. None-the less, laws prevail that impose harsh burdens based on racial classification. These laws define sharp boundaries to separate one race from another. Simplistic resolutions of racial ambiguity are the one-drop rules that asserted that any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry ('one drop' of 'black blood') is considered black. Attempts to define Native American identity in the United States encounters similar difficulties.

The map is not the territory.[edit | edit source]

As soon as we label an object to represent it, use a mental model, invoke an analogy, use a metaphor, substitute a representation for a thought, idea, or object, or substitute an interpretation for some set of observations we substitute the map for the territory.

Our brain learns a model of the world. Intelligence is tied to the model the brain creates. [10] The brain learns its model of the world by observing how its inputs change over time. [11] The neocortex learns a predictive model of the world. [12]

We rely on the map our brain creates to navigate the world we live in. This works best when our mental maps correspond accurately to the real world. We navigate through life guided by the mental representations that form in our brains. If you are now sitting on a chair in a room, and you want to leave that room, you rely on your mental image of the chair, your location in the room, and the location of the door. If this mental model is wrong, you will have difficulty getting out of the chair, walking across the room, opening the door, and walking through.

We know the map is not the territory, but merely some simplified and often distorted representation of the corresponding territory—reality as it is. Whenever we rely on the map rather than the territory for forming beliefs, deciding, or planning actions, we risk misrepresenting the territory and embracing a distorted view of reality.

George Box reminds us that “All models are wrong, some are useful”.

We depart from reality the moment we move from perception to conception from observation to interpretation. In his painting The Treachery of Images, René Magritte reminds us that an image of a pipe is a representation of the pipe and not the pipe itself.

It is difficult to be precise and neutral in our language. Language provides many opportunities to be vague, ambiguous, nonsensical, prejudicial, emotional, laudatory, persuasive, kind, cruel, vacuous, or equivocal. Because rhetoric is the art of persuasion, be aware that it can draw you toward a conclusion and influence your beliefs using only baseless arguments and emotional manipulation.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Notice as conflicts arise in conversations, debates, and arguments.

- Determine if the disagreement is at the level of language, perception, or reality.

- Practice dialogue rather than debate or argumentation. Be candid. Advance no falsehoods.

- Lead the dialogue toward reality and away from abstractions. Move toward the center (reality as it is) of the Layers of Abstraction diagram at the beginning of this course.

- Find common ground within our shared reality.

- Don’t argue matters of fact, research them.

- Seek true beliefs.

- Align your worldviews with reality.

- Transcend conflict.

Interpretation[edit | edit source]

People interpret observations to resolve ambiguity, increase certainty, and to account for observations within some familiar model or analogy. The role of interpretation is most evident when the items being interpreted are most ambiguous.

Tea Leaves[edit | edit source]

Tasseography is the art of interpreting patterns in tea leaves, coffee grounds, or wine sediments. The diviner—a person skilled in interpreting tea leaves—looks at the pattern of tea leaves in the cup and allows the imagination to play around with the shapes suggested by them. They might look like a letter, a heart shape, a ring, or anything else. These shapes are then interpreted intuitively or by means of some system of symbolism. Images formed in a cup are created and uniquely seen by the reader, so it is often said that the only limitation for cup reading is the imagination of the reader themselves.

Tasseography reveals the essence of interpretation at an extreme. Because the tea leaf formations are entirely arbitrary the interpreter can say almost anything. The interpretation reflects judgements, evaluations, biases, concepts, models, analogies, predictions, optimism, pessimism, certainty, risk, doubt, hope, fears, storytelling skills, and desires of the interpreter, entirely independent of the tea leaf formation.

Rorschach tests, astrology, horoscopes, biorhythms, tarot card reading, Ouija, fortune telling, and dream interpretations are similar to tasseography in that they all depend more on the person doing the interpretation than on the ambiguous items being interpreted.

Recognizing the extent of ambiguity inherent in the various representations we use to describe reality, interpretation plays a significant role in influencing our understanding and beliefs. Adopting an interpretation can obscure and nearly occlude the underlying reality. Keep your eye on the territory as others offer various maps they would like you to use instead. Continue to reference reality so you can evaluate, challenge, and often reject, various interpretations.

Reality, Perception, and Interpretation[edit | edit source]

The parable of the blind men and the elephant provides an example that can help us examine the distinctions among reality, perception, and interpretation. In the parable is a story of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant before and who learn and imagine what the elephant is like by touching it. Each blind man feels a different part of the elephant's body, but only one part, such as the tail or the tusk. They then describe the elephant based on their limited experience and their descriptions of the elephant are different from each other.

The elephant is an example of reality—what exists in the world. Each of the blind men makes some limited observations and forms a perception of the elephant. Each of these perceptions is based a small sample of reality. The man at the tail accurately perceives the tail by sensing how it feels. The man at the tusk accurately perceives the tusk, also by sensing how it feels. Then each man interprets his (limited) observation. The man at the tail concludes an elephant is like a rope, the man at the tusk concludes the elephant is hard, smooth, and like a spear.

Each blind man makes errors when interpreting their perceptions:

- Each fails to include the observation of the others, and if they consult the other observers, they fail to trust these additional observations and integrate them into a consistent whole.

- Each overgeneralizes from their limited experience to draw conclusions about the entire elephant.

- Each interprets their observations in terms of existing paradigms (rope, spear) rather than considering new paradigms (elephant).

Recall the differing yet equally correct interpretations of the rabbit-duck illusion. This simple image allows for two different, yet equally correct interpretations. Life is often more complicated than ducks and rabbits, and we can reasonably differ in interpreting many words.

The second amendment to the United States Constitution is the subject of long and contentious interpretations. It states:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

The (sometimes omitted) commas in the text draw much attention. The Militia clause is especially open to interpretation. Indeed, most of the words in this short statement have been interpreted in a variety of ways. Interpretation of this text is the subject of many court cases and continues to sharply divide political discourse in the United States.

Innuendo and plausible deniability disingenuously equivocate on interpretation.

Learn to embrace ambiguity. Become comfortable with doubt. Examine and reevaluate your preconceptions. Avoid tragic misinterpretations.

Tragic Interpretations[edit | edit source]

Interpretations that prematurely eliminate doubt and resolve ambiguity into a comfortable yet false feeling of certainty have led to several tragedies. Here are some prominent examples.

- It has long been observed that the sky brightens each morning and day turn to darkness each evening. The causes of this were ambiguous for most of recorded history. Perhaps the sun moves around the earth on a celestial sphere. Alternatively, the earth could rotate on its axis as it revolves around the sun. The pope was certain the earth was the center of the universe, Galileo differed. The contentious debate over these alternative interpretations of the observations culminated with the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633.

- In 1997 members of the Heaven’s Gate new religious movement misinterpreted images of the Hale-Bopp comet, and decided that the only way to evacuate this earth was to participate in a mass suicide. Cults are often formed based on alternative interpretations of events.

- Although the phrase “All men are created equal” motivated the revolution that formed the United States, differing interpretations of the status of slaves as being either property or being humans led to the civil war.

- Religious groups often differ in the interpretation of various symbols, texts, and prophesies. Here are some examples.

- Christianity is a religion based on interpretations of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. These interpretations lead to the belief that Jesus is the Son of God, whose coming as the messiah was prophesied in the Hebrew Bible and chronicled in the New Testament.

- The differences between Christianity and Judaism originally centered on whether Jesus was the Jewish Messiah but eventually became irreconcilable. Followers of Judaism interpret the life of Jesus to be that of a well-meaning and charismatic human who worked as carpenter, but not the Messiah. This difference in interpretation led to the holocaust.

- Islam is a religion teaching that Muhammad is a messenger of God. The primary scriptures of Islam are the Quran, interpreted as the verbatim word of God. Various denominations differ in their interpretations of the rightful successors of Muhammad. This difference in interpretation has led to sectarian warfare.

- Scientology, classified as a religion by the United States Internal Revenue Service, is a set of beliefs and practices invented by American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It has been variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religious movement, depending on various interpretations of the various beliefs and practices.

- Nontheists study reality and recognize that non-theism is the parsimonious worldview. Therefore, theists who make supernatural claims bear the (unmet) burden of proving their supernatural claims. Nontheists may risk persecution for blasphemy.

- Religious wars, often resulting from disputes over these various interpretations, are frequent, long lasting, and deadly. Matthew White's The Great Big Book of Horrible Things gives religion as the primary cause of 11 of the world's 100 deadliest atrocities.

- The nature of the 2021 United States Capitol attack has been widely, passionately, and variously interpreted. Former attorney general William Barr, who had resigned days earlier, denounced the violence, calling it "outrageous and despicable", adding that the president's actions were a "betrayal of his office and supporters" and that "orchestrating a mob to pressure Congress is inexcusable." None-the-less, the Republican National Committee contended that the lethal riot was an example of "legitimate political discourse." The aftermath continues to have important political, legal, and social repercussions.

- Various conspiracy theories are based on alternative interpretations of events. Here are a few selected from a much longer list of conspiracy theories.

- Many conspiracy theories concerning the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 have emerged. Many of these depend on various interpretations of the available evidence and are especially skeptical of the single bullet theory—the official description of the event appearing in the Warren commission report. It is also frequently asserted that the United States federal government intentionally covered up crucial information in the aftermath of the assassination to prevent the conspiracy from being discovered.

- The multiple attacks made on the US by terrorists using hijacked aircraft on September 11, 2001 have proven attractive to conspiracy theorists. Theories may include reference to missile or hologram technology. By far, the most common theory is that the attacks were in fact controlled demolitions, a theory which has been rejected by the engineering profession and the 9/11 Commission.

- The "Deep state" often refers to discredited allegations of an unidentified "powerful elite" who act in coordinated manipulation of a nation's politics and government. Proponents of such theories have included Canadian author Peter Dale Scott, who has promoted the idea in the US since at least the 1990s, as well as Breitbart News, Infowars and former US President Donald Trump. A 2017 poll by ABC News and The Washington Post indicated that 48% of Americans believe in the existence of a conspiratorial "deep state" in the US. Some of these theories promote QAnon conspiracy theories which are based on the interpretation of false claims made by an anonymous individual or individuals known as "Q".

- Anti-vaccination activists and other people in many countries have spread a variety of unfounded conspiracy theories and other misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines based on misinterpreted or misrepresented science, religion, exaggerated claims about side effects, a story about COVID-19 being spread by 5G, misrepresentations about how the immune system works and when and how COVID-19 vaccines are made, and other false or distorted information. This has prolonged the pandemic and caused political unrest.

- Quackery, crystal healing, homeopathy, and other ineffective and fraudulent health claims waste time and money while deceiving patients and delaying effective treatments. These are sustained by inaccurate interpretation of evidence.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Notice as conflicts arise in conversations, debates, and arguments.

- Determine if the disagreement is at the level of interpretations, language, perception, or reality.

- Identify the specific interpretations that differ.

- Identify the ambiguities that allow for various interpretations.

- Cast doubt on the certainty of any specific interpretation.

- Practice dialogue rather than debate or argumentation. Be candid. Advance no falsehoods.

- Lead the dialogue toward reality and away from abstractions. Move toward the center (reality as it is) of the Layers of Abstraction diagram at the beginning of this course.

- Find common ground within our shared reality.

- Don’t argue matters of fact, research them.

- Embrace ambiguity.

- Seek true beliefs.

- Align your worldviews with reality.

- Transcend conflict.

Narration[edit | edit source]

Humans enjoy telling and retelling stories. Myths have been a part of human culture for at least as long as recorded history. Folklore, oral traditions, epics, creation myths, campfire stories, fairy tales, legends, bedtime stories, songs, poems, and soap operas are told and retold. Stories provide a memorable, coherent, compelling, and plausible explanation for events. They are also often fanciful and factually unfounded.

In his book Sapiens: A Brief History Of Humankind, author Yuval Harari claims that all large-scale human cooperation systems – including religions, political structures, trade networks, and legal institutions – owe their emergence to Sapiens' distinctive cognitive capacity for fiction. Ours is the storytelling species.

Narratives that stick[edit | edit source]

Why is it that some ideas survive while others die? According to the book Made to Stick, an idea becomes memorable or interesting when it is:

- Simple – find the core of any idea or thoughts

- Unexpected – grab people's attention by surprising them

- Concrete – make sure an idea can be grasped and remembered later

- Credible – give an idea believability and credibility

- Emotional – help people see the importance of an idea

- Presented as a story – empower people to use an idea through narrative

Several grand narratives currently divide our worldviews and political discourse in the United States. Conservatives often agree with Ronald Regan that “Government is the Problem”, while progressives tend to believe that “Government is the solution”. Each tribe can cite many examples bolstering their position. Beginning with their chosen narrative, conservatives often oppose mask mandates, while progressives blame the unmasked for endangering others and prolonging the pandemic. These arguments begin with narratives and extend to interpretations and representative symbols but are rarely based on a careful evaluation of evidence.

Americans are divided by several such narratives. More guns make us safer, or they cause needless violence. Climate change is the biggest threat to our future or is simply a hoax. Abortion murders babies or protects a women’s constitutional right to choose. God created man, or man created God. Earth belongs to man or man belongs to earth. Capitalism is the solution or capitalism is the problem. Do you believe the experts or do you believe your friends? Various conspiracy theories provide especially troublesome narratives. Ideologies amplify cognitive biases.

Powerful False Narratives[edit | edit source]

Very often, the best story wins. Here is an example of a powerful, influential, and harmful false narrative, known as the satanic panic.

The Satanic panic is a moral panic consisting of over 12,000 unsubstantiated cases of Satanic ritual abuse (SRA) starting in the United States in the 1980s, spreading throughout many parts of the world by the late 1990s, and persisting today. The panic originated in 1980 with the publication of Michelle Remembers, a bestselling book co-written by Canadian psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder and his patient (and future wife), Michelle Smith, which used the discredited practice of recovered-memory therapy to make sweeping lurid claims about satanic ritual abuse involving Smith. The allegations which afterwards arose throughout much of the United States involved reports of physical and sexual abuse of people in the context of occult or Satanic rituals. In its most extreme form, allegations involve a conspiracy of a global Satanic cult that includes the wealthy and powerful world elite in which children are abducted or bred for human sacrifices, pornography, and prostitution.

The key elements of the narrative are:

- Satanic ritual abuse is horrific and widespread.

- Unknown to us many of our children are being subjected to the horrors of satanic ritual abuse.

- The abuse is so horrible that the children repress their memories of the abuse and are unable to disclose their experiences.

- A newly developed interviewing technique, called recovered-memory therapy, can elicit accurate memories and testimony from the children.

- Using this technique, many children are beginning to reveal and describe the abuse they have suffered.

- This must be urgently investigated, and the abuse stopped at all costs.

- A global Satanic cult may be responsible.

- Missing memories among the victims and absence of evidence was cited as evidence of the power and effectiveness of the cult in furthering their agenda.

Initial interest arose via the publicity campaign for Pazder's 1980 book Michelle Remembers, and it was sustained and popularized throughout the decade by coverage of the McMartin preschool trial and the contemporaneous day-care sex-abuse hysteria. Testimonials, symptom lists, rumors, and techniques to investigate or uncover memories of SRA were disseminated through professional, popular, and religious conferences, as well as through talk shows, sustaining and further spreading the moral panic throughout the United States and beyond. In some cases, allegations resulted in criminal trials with varying results; after seven years in court, the McMartin trial resulted in no convictions for any of the accused, while other cases resulted in lengthy sentences, some of which were later reversed. Scholarly interest in the topic slowly built, eventually resulting in the conclusion that the phenomenon was a moral panic, which, as one researcher put it in 2017, "involved hundreds of accusations that devil-worshipping pedophiles were operating America's white middle-class suburban daycare centers."

Of the more than 12,000 documented accusations nationwide, investigating police were not able to substantiate any allegations of organized cult abuse.

Today the far-right conspiracy theory movement known as QAnon, has adopted many of the tropes of Satanic Ritual Abuse and Satanic Panic. Instead of daycare centers being the center of abuse, however, liberal Hollywood actors, Democratic politicians, and high-ranking government officials are portrayed as a child-abusing cabal of Satanists.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

Part 1:

- Identify a powerful false narrative to study for this assignment. Choose one from this list of powerful false narratives, or from any other source.

- Identify the elements that make this narrative compelling, convincing, memorable, and likely to spread and be shared with others.

- Identify the falsehoods in the narrative.

- Identify any ambiguities that are prematurely resolved.

- Identify the various calls to action inspired by the narrative.

- How is this narrative harmful, if at all?

- Who gains and who loses as this narrative spreads?

Part 2:

- Notice as conflicts arise in conversations, debates, and arguments.

- Determine if the disagreement is at the level of narrative, language, perception, or reality.

- If the narrative is driving the conversation, go through the steps above to analyze the narrative elements.

- Practice dialogue rather than debate or argumentation. Be candid. Advance no falsehoods.

- Lead the dialogue toward reality and away from abstractions. Move toward the center Move toward the center (reality as it is) of the Layers of Abstraction diagram at the beginning of this course.

- Find common ground within our shared reality.

- Don’t argue matters of fact, research them.

- Seek true beliefs.

- Embrace ambiguity.

- Align your worldviews with reality.

- Transcend conflict.

Ideology[edit | edit source]

Do you think for yourself and choose your own beliefs? If you are like most people, you probably find it easier to adopt some pre-packaged set of beliefs that seem attractive. We can broadly characterize an ideology as some agenda-driven set of beliefs.[13] Because ideologies are constructed to serve some agenda, an ideology is unlikely to accurately represent reality.

An ideology is a set of beliefs intended to describe how the world works, or how some believe it should work. An ideology is a particular way of looking at the world, often codified into a doctrine. Often our religious, political, and economic beliefs are drawn from an ideology. You may also follow particular lifestyle choices such as veganism, or environmentalism based on a particular ideology. Ideologies substitute socially constructed models for brute facts. Many ideological models do not correspond well to reality. “Essentially, all models are wrong,” George Box noted, “but some are useful.” Beware of substituting an ideology for a careful examination of reality.

As illustrated in the revised diagram shown here, ideologies impose a model that prohibits direct access to reality, and displaces any alternative narratives, interpretations, representations, or perceptions of reality. The ideology establishes all you need to know. It acts as a convenient substitute for reality.

Immersion and commitment to an ideology can become a firmly held part of your identity. If you say “I am a Conservative” rather than “I often agree conservative political ideas” you are declaring the ideology as a part of your identity.[14] This can make it harder to abandon. Although you choose your beliefs, you are not your beliefs.

Remaining bound by an ideological doctrine is a form of mental bondage. It is wise to break free from that bondage. Adopting a scout mindset—described below—can help us break free from ideologies that are holding our minds captive.

The Scout Mindset[edit | edit source]

Author Julia Galef describes the scout mindset as “The motivation to see things as they are, not as you wish they were.”[15] In contrast to the scout mindset, the soldier mindset is a motivation to attack differing points of view or defend a position in each argument we encounter.

Contrasted with the soldier mindset, the scout mindset values:

- Seeing things as they are over defending territory or taking territory;

- Asking is it true? over arguing to defend a pre-determined position;

- Observations over interpretations;

- Investigation over argumentation;

- Gaining insight over winning this argument;

- Wonder over attacking;

- Learning over advancing a position;

- Observing over taking ground;

- Understanding the issue over shooting down arguments;

- Exploring possibilities over reinforcing a position;

- Seeking true beliefs over securing long held beliefs;

- Seeking reality over defending an ideology;

- Objective evidence over motivated reasoning;

- Representative evidence over narratives, specious interpretations and representations;

- Reason over rhetoric;

- Exploration over staying on the ideological course;

- Dialogue over reciting dogma;

- Listening over reiterating and continuing to advocate;

- Humility over arrogance;

- Curiosity over certainty or fear;

- Intellectual honesty over prevarication, and

- Working with collaborators over fighting with opponents.

Ego encourages the soldier. Reason encourages the scout.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Law and Ideology tells us, “Ideologies are ideas whose purpose is not epistemic, but political. Thus, an ideology exists to confirm a certain political viewpoint, serve the interests of certain people, or to perform a functional role in relation to social, economic, political, and legal institutions.” [16]

Because ideologies exist to advance an agenda rather than to model reality, they require a soldier mindset to sustain the gap between the model described by the ideology and an accurate model based on reality. Ideologies are vulnerable to exploration by a scout mindset. Adopting a scout mindset is key to escaping ideologies.

Example Ideologies[edit | edit source]

We rely on many ideologies to simplify our thinking. These include:

- Loyalty, including loyalty to an individual person, a group, team, brand, causes, regions, nation, or any of the belief systems listed below.

- Myths and legends,

- Folklore, traditions, superstitions, and taboos,

- Caste systems, including racism, sexism, other forms of ascribed status, social classes, and other ranking constructs,

- Stereotypes,

- Economic ideologies, including neoliberalism, monetarism, mercantilism, mixed economy, social Darwinism, communism, laissez-faire economics, and free trade. There are also current theories of safe trade and fair trade that can be understood as ideologies.

- Political ideologies, including anarchism, authoritarianism, communism, conservatism, democracy, environmentalism, fascism, separatist movements, liberalism, libertarianism, nationalism, populism, social democracy, socialism, and others.

- Creation myths,

- Religions and spiritual traditions,

- Quackery,

- Pseudoscientific beliefs,

- Paranormal beliefs,

- Commitment to conspiracy theories, and

- New religious movements.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

Part 1:

- Identify each of the ideologies you identify with, belong to, or agree with. Use the list above as a guide or use any other method to identify ideologies that influence you.

- For each of the ideologies identified in step 1:

- Decide if the model it presents is an accurate representation of reality in all its scope and complexity.

- Identify any ambiguities that are prematurely resolved.

- Decide if the ideology is helping you understand reality, or is occluding, limiting, biasing, or censoring your understanding of reality.

- If you decide a particular ideology is unhelpful, take steps to abandon that ideology.

Welcome those who are seeking truth. Abandon those who are certain they have found Truth.

Part 2:

- Study the module on Examining Ideologies within the Knowing how you know course.

- Complete the assignments in that module.

- Think beyond the doctrine.

Toward Ought[edit | edit source]

So far in this course, the common ground we have considered is our shared reality. This is our collective understanding of what is in the world. Can we find a corresponding common ground regarding what we ought to do?

Philosopher David Hume famously observed that knowing only what is, we cannot determine what we ought to do. However, by making the reasonable assumption of impartiality, we can begin to identify what it is we ought to do.

We ought to advance human rights worldwide, adopt pro-social values, and establish a well-founded basis for moral reasoning.

Assignment[edit | edit source]

- Complete the Wikiversity course on Assessing Human Rights.

- Advance human rights, worldwide.

- Study this list of pro-social values.

- Adopt pro-social values and choose level 5 living.

- Complete the Wikiversity course on Moral Reasoning.

- Develop your own well-founded basis for moral reasoning.

Simple but not easy[edit | edit source]

The central idea in this course—reality is our common ground—is simply stated and supported by overwhelming evidence. However, it may not be easy for you, or others you encounter or care about to change deeply held beliefs that differ from objective reality. Here are some steps you can take to align your beliefs with reality and work to find common ground with others.

- Begin by aligning your own beliefs with reality. Complete the course on Seeking True Beliefs. Align your own worldview with reality. Think clearly. Know how you know. Become skillful at evaluating evidence. Stay curious. Embrace ambiguity.

- Be careful to distinguish among matters of fact, matters of controversy, and matters of opinion. Do not argue matters of fact, research them. Do not argue matters opinion, enjoy them. Reason carefully and listen closely when discussing matters of controversy. Although tolerance is essential in matters of opinion, it has no place in matters of fact.

- Spend the required effort to prepare to find common ground with others.

- Complete the course on practicing dialogue. Practice dialogue.

- Ensure all participants have adopted a Socratic temperament.

- Expect intellectual honesty.

- Complete the course on intellectual honesty.

- Advance no falsehoods.

- Discuss the importance of intellectual honesty—accurately describing your true beliefs—with each participant. Gain agreement to be intellectually honest, and to expect intellectual honesty from all participants. Do not indulge charlatans. Do not feed the trolls.

- Finding common ground often challenges deeply held beliefs. This is uncomfortable; people often react with fear and may seek to withdraw from the dialogue or divert the conversation. Notice the shift from scout mindset to soldier mindset. Notice when fear begins to displace curiosity. Encourage the fearful person to allow curiosity to displace fear. Return to a scout mindset.

- The course on Street Epistemology provides specific techniques for exploring the basis for beliefs. Use applicable Street Epistemology techniques when seeking common ground.

Summary and Conclusions[edit | edit source]

Reality exists. Reality is vast, complex, and dynamic. Humans have only investigated a small portion of the universe, and our investigation is incomplete. We all live together on this one planet we call Earth and we all live in the same universe.

Because we all live in the same universe, our reliable understanding of that universe must eventually converge toward one coherent description. Because reality exists, we can examine reality, and we can align our worldview with reality. Building on these observations, it follows that reality is our common ground, even though any number of worldviews is possible.

Perception transforms sensory information originating with some material object, known as the target or the distal stimulus into mental representations known as percepts, which do not exist elsewhere in the world.

Perception—the process of extracting information from energy that impinges on our sensory organs—is not straightforward. There is more to perception than meets the eye.

Our most direct encounters with reality are through direct sensory observations and awareness. However, our perceptions are not exact replicas of the distal objects being perceived. Omissions, distortions, and additions take place. Fortunately, we can augment our direct perceptions to obtain a more accurate understanding of our world. Furthermore, perceptions are personal, and it is often a mistake to generalize our personal perceptions beyond our own experiences.

We represent our thoughts using various symbols, including words, gestures, facial expressions, images, and analogies. The mapping from various representations to reality is imprecise. Language and other symbols can be constraining, ambiguous, refer to social constructs, prejudiced, based on artificial boundaries, or focus on convenient representation rather than reality. The map is not the territory, although we often confuse our representations for realty.

People interpret observations to resolve ambiguity, increase certainty, and to account for observations within some familiar model or analogy. The role of interpretation is most evident when the items being interpreted are most ambiguous.

Tasseography—reading tea leaves—reveals the essence of interpretation. Because the tea leaf formations are entirely arbitrary the interpreter can say almost anything. The interpretation reflects judgements, evaluations, biases, concepts, models, analogies, predictions, optimism, pessimism, certainty, risk, doubt, hope, fears, storytelling skills, and desires of the interpreter, entirely independent of the tea leaf formation.

The rabbit-duck illusion allows for two different, yet equally correct interpretations. Life is often more complicated than ducks and rabbits, and we can reasonably differ in interpreting many words.

Interpretations that prematurely eliminate doubt and resolve ambiguity into a comfortable feeling of certainty have led to several tragedies. Become comfortable with ambiguity.

Humans enjoy telling and retelling stories. This may be the defining characteristic of the human species. We are exposed to many powerful false narratives. To find common ground we must dismiss the falsehoods in narratives.

An ideology is a set of beliefs intended to describe how the world works, or how some believe it should work. An ideology is a particular way of looking at the world, often codified into a doctrine. Often our religious, political, and economic beliefs are drawn from an ideology.

Ideologies substitute socially constructed models for brute facts. Many ideological models do not correspond well to reality. “Essentially, all models are wrong,” George Box noted, “but some are useful.” Beware of substituting an ideology for a careful examination of reality.

Remaining bound by an ideological doctrine is a form of mental bondage. It is wise to break free from that bondage. Adopting a scout mindset can help us break free from ideologies that are holding our minds captive.

It is likely your beliefs are influenced by inaccurate ideologies. Identify these and abandon them.

This is not about compromise. This is about gaining an accurate understanding of the world we live in.

Reality is our reference standard.

Embrace reality. Seek true beliefs. Dismiss misleading perceptions, representations, interpretations, narrations, and ideologies. Align concepts with reality.

Advance human rights worldwide, adopt pro-social values, and establish a well-founded basis for moral reasoning.

It is difficult to change deeply held beliefs, however if you can do this, they can do this.

We can find common ground.

Recommended Reading[edit | edit source]

- Van der Stigchel, Stefan (March 12, 2019). How Attention Works: Finding Your Way in a World Full of Distraction. The MIT Press. pp. 152. ISBN 978-0262039260.

- Rogers, Brian (December 26, 2017). Perception: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 144. ISBN 978-0198791003.

- Gause, Donald C.; Weinberg, Gerald M. (March 1, 1990). Are Your Lights On?: How to Figure Out What the Problem Really Is. Dorset House Publishing Company. pp. 176. ISBN 978-0932633163.

- Weinberg, Gerald M. (September 1, 1989). Exploring Requirements: Quality Before Design. Dorset House Publishing Company. pp. 320. ISBN 978-0932633132.

- Holmes, Jamie (October 11, 2016). Nonsense: The Power of Not Knowing Paperback. Crown. pp. 336. ISBN 978-0385348393.

- Burton M.D., Robert A. (Mar 17, 2009). On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You're Not. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312541521.

- Duke, Annie. Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don't Have All the Facts. Portfolio. pp. 288. ISBN 978-0735216372.

- Freinacht, Hanzi (March 10, 2017). The Listening Society: A Metamodern Guide to Politics. Metamoderna ApS. pp. 414. ISBN 978-8799973903.

- Freinacht, Hanzi (May 29, 2019). Nordic Ideology: A Metamodern Guide to Politics. Metamoderna ApS. pp. 495. ISBN 978-8799973927.

- Gilovich, Thomas; Ross, Lee (December 1, 2015). The Wisest One in the Room: How You Can Benefit from Social Psychology's Most Powerful Insights. Free Press. pp. 320. ISBN 978-1451677546.

- Galef, Julia (April 13, 2021). The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don't. Piatkus. ISBN 978-0349427645.

- Hawkins, Jeff (March 2, 2021). A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence. Basic Books. pp. 288. ISBN 978-1541675810.

- Hofstadter, Douglas R; Sander, Emmanuel (April 23, 2013). Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking. Basic Books. pp. 592. ISBN 978-0465018475.

- Weinberg, Gabriel (June 18, 2019). Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models. Portfolio. pp. 352. ISBN 978-0525533580.

- Stone Zander, Rosamund; Zander, Benjamin (224). The Art of Possibility: Transforming Professional and Personal Life. Penguin. pp. 224. ISBN 978-0142001103.

- Lakoff, George; Johnson, Mark (April 15, 2003). Metaphors We Live By. pp. 242. ISBN 978-0226468013.

- Heath, Chip; Heath, Dan. Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die. Random House. pp. 291. ISBN 978-1400064281.

- Grant, Adam (February 2, 2021). Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know. Viking. pp. 320. ISBN 978-1984878106.

- Campbell, Joseph; Moyers, Bill (June 1, 1991). The Power of Myth. Anchor. pp. 293. ISBN 978-0385418867.

- Mackay, Charles (November 1, 2016). Extraordinary Popular Delusions and The Madness of Crowds. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 386. ISBN 978-1539849582.

- Orwell, George (March 1, 2017). Animal Farm. Fingerprint! Publishing. pp. 152. ISBN 978-9386538284.

- Orwell, George (January 15, 2013). Politics and the English Language. Penguin Classic. pp. 48. ISBN 978-0141393063.

- Hecht, Jennifer Michael (September 7, 2004). Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson. HarperOne. pp. 576. ISBN 978-0060097950.

- Carroll, Sean M (May 4, 2017). The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself. Oneworld Publications. pp. 480. ISBN 978-1786071033.

- Pinker, Steven (February 13, 2018). Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. Viking. pp. 576. ISBN 978-0525427575.

- Wilczek, Frank (January 12, 2021). Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality. Penguin Press. pp. 272. ISBN 978-0735223790.

- Gray, Dave (September 14, 2016). Liminal Thinking: Create the Change You Want by Changing the Way You Think. Two Waves Books. pp. 184. ISBN 978-1933820460.

I have not yet read the following books, but they seem interesting and relevant. They are listed here to invite further research.

- Coleman, Peter T. (June 1, 2021). The Way Out: How to Overcome Toxic Polarization. Columbia University Press. pp. 296. ISBN 978-0231197403.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ This diagram is used as the primary organizing structure for the course. Each ring in the diagram corresponds to a section of the course. Notice that each boundary is blurred. This blurring acknowledges that the various layers interact and no sharp boundary between layers exists.

- ↑ According to Aumann's agreement theorem, we will be able to find common ground.

- ↑ Although I am very confident that reality exists, no one can be certain. Much of this course demonstrates the value of embracing and exploring doubt while deferring certainty. Also, it is often wise to think in bets. See: Duke, Annie. Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don't Have All the Facts. Portfolio. pp. 288. ISBN 978-0735216372.

- ↑ This assumption does not conflict with many-worlds interpretations of quantum mechanics.

- ↑ Rogers, Brian (December 26, 2017). Perception: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 144. ISBN 978-0198791003.Page 13 of 162.

- ↑ Rogers, Brian (December 26, 2017). Perception: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 144. ISBN 978-0198791003.Page 13 of 162.

- ↑ Siegel, Susanna, "The Contents of Perception", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Section 4.1.

- ↑ 100 Uses for Paperclips, See: https://leoniehallatinnovationiq.wordpress.com/2012/11/21/100-uses-for-paperclips/

- ↑ Gause, Donald C.; Weinberg, Gerald M. (March 1, 1990). Are Your Lights On?: How to Figure Out What the Problem Really Is. Dorset House Publishing Company. pp. 176. ISBN 978-0932633163. @128 of 255.

- ↑ Hawkins, Jeff (March 2, 2021). A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence. Basic Books. pp. 288. ISBN 978-1541675810.@22 of 384

- ↑ Hawkins, Jeff (March 2, 2021). A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence. Basic Books. pp. 288. ISBN 978-1541675810. @66 of 384

- ↑ Hawkins, Jeff (March 2, 2021). A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence. Basic Books. pp. 288. ISBN 978-1541675810.@75 of 384